Innovation, innovation, innovation.

It’s the rain dance chant in breakfast meetings, business seminars and policy sessions. It’s the mystic ingredient peppered through every white paper and strategic plan. Innovation, according to many, is a prime solution to some of our region’s chronic economic problems – whether it be Trinidad and Tobago’s in oil and gas dependency or the wider Caribbean’s inability to adapt to competitive pressure.

But innovation has so far been as elusive as it is enticing. In the most recent Global Competitiveness Report of the World Economic Forum, Trinidad ranks in the bottom third (100 out of 144 countries) in innovation. “Insufficient capacity to innovate” is the country’s sixth most problematic factor to doing business.

The nation has taken steps to spark innovation, two of the most visible of these being the Council for Competitiveness and Innovation’s “Ideas 2 Innovation” competition and the recent (October 2014) partnership with the European Union through which Trinidad and Tobago will receive a 9.7 million euro grant to boost innovation.

Yet despite this thirst for innovation and the willingness to mobilise considerable resources towards fostering it, there is an obvious resource for ideas and inventions that remains largely untapped – The University of the West Indies.

Ideas to food processing

Imagine a machine that vacuum extracts the water from coconuts, tripling its shelf life. How about a piece of equipment that reduces the tedious preparation time of bread nut (chataigne) from over an hour to ten minutes. What could a whole suite of machinery that reduces the need for labour, accelerates processes and lowers costs do for the regional agro-processing industry?

For five years now students from the Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering within the Faculty of Engineering have been developing models for an array of food preparation and processing purposes. How viable are these inventions?

“About 60-70% of these models could be implemented,” says Rodney Harnarine, a development engineer in the department and supervisor for numerous student projects.

This is the kind of potential that planners and policymakers have been looking for, a ready-made innovation incubator. But to turn that potential into opportunity many things need to happen – and they haven’t been happening. Without support a potential innovation garden can become a graveyard for good ideas.

Resurgence of agriculture

To understand how timely a concept agro-processing innovation is, you have to understand how topical food production and security has become for the region.

On May 2 of this year, Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) Director-General José Graziano da Silva told a the gathering of CARICOM heads in the Bahamas that agriculture was crucial for the region to achieve food security and could spur economic growth.

“Agriculture has really taken on a new life,” says Dr Wayne Ganpat, lecturer in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension within the Faculty of Food and Agriculture. “(The Caribbean) is searching for the right mix of commodities to rebuild agriculture’s contribution to GDP.” “Agriculture has really taken on a new life,” says Dr Wayne Ganpat, lecturer in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension within the Faculty of Food and Agriculture. “(The Caribbean) is searching for the right mix of commodities to rebuild agriculture’s contribution to GDP.”

Agro-processing is seen as an important way of adding value to agricultural commodities – extending the shelf life or perishable items, creating employment and bringing in new revenues. And innovation can enhance every aspect of the food production sector – pre-primary production, production, processing and even spin-off industries like agro-tourism.

“We want bright young people, innovators and entrepreneurs moving forward. The agriculture we want is one that is smart,” says Dr Ganpat.

And within the campus itself there are many bright young people bringing their creative abilities to the requirements of the agro-processing industry. Turns out the solution to spurring innovation is as simple as the old saying – “necessity is the mother of invention”.

Students within the Mechanical Engineering Department are required to complete a design and build project for their degree programme. Agro-processing and food production is one of six areas they can choose for their project. That means every year between 80-100 students are creating systems or equipment and some of them are working in agro-processing.

“Typically I would have 10 projects a year,” says Mr Harnarine, who supervises many of the agro-processing projects and is a major advocate for pushing the innovation being produced beyond the boundaries of the classroom for the benefit of the students, The UWI and the food production industry.

Innovation factory

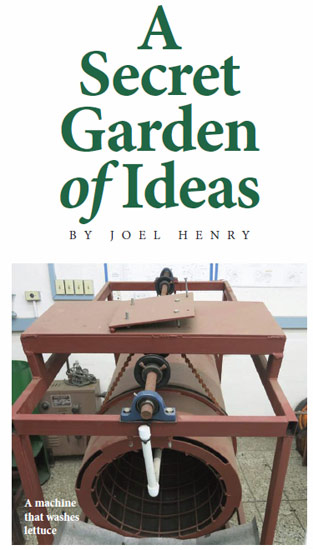

What kinds of projects have been developed? Besides the vacuum extractor and bread nut shredder, innovations include a papaya pulper; a soursop seed separator; a green mango slicer; devices that wash, peel, grate and dry cassava for the production of cassava flour; a cocoa pod splitter and many more.

“Very often what the students build is not a prototype, but a scaled-down model using substitute materials, Mr Harnarine explains. “None the less these are the basis for new ideas and new equipment.”

Materials are one of many challenges the students face, challenges that are weighing down what could be the genesis of a new relationship between the university and the market.

“The students are under pressure doing five other courses besides their project,” Mr Harnarine says. “Somewhere between their courses and the weekend they find time to build equipment. Money is also a problem. You have 100 students trying to raise $5,000 to buy bits and pieces to put together.”

Add to that the department’s limited manpower and resources, and it’s clear that the students are producing extraordinary work in less than optimal conditions. But the most difficult part of this scenario is what happens after the projects are completed:

“We do not have storage space for 100 projects every year. So every year, if there is no interest in a project we will scrap it and recycle the motor and other usable parts.”

Innovation is a culture

When looking at the lack of business innovation in the Caribbean it is important to understand that there are several structural impediments within our societies. The inertial forces are at present much stronger than the forces for movement, development and change. And although there is a greater urgency for innovation being expressed at very high levels, the machinery to make it so is often sluggish and highly inaccurate in its movement. When looking at the lack of business innovation in the Caribbean it is important to understand that there are several structural impediments within our societies. The inertial forces are at present much stronger than the forces for movement, development and change. And although there is a greater urgency for innovation being expressed at very high levels, the machinery to make it so is often sluggish and highly inaccurate in its movement.

As one of the most important regional institutions, boasting a repository of some of its brightest minds and operating under a mandate to make the Caribbean a better place, The UWI is in a position to make a tremendous impact on the fostering of an innovative culture. The work of students in agro-processing innovation is an area in which The UWI can have that kind of impact.

What are some of the changes that need to take place for the evolution of what could become a campus innovation unit?

External partnerships/funding – Resources such materials, manpower and space require funding. Universities that produce innovative technologies work closely with their governments and the private sector. Increased funding opens up all kinds of opportunities.

Stronger linkages with manufacturing training institutions – Training institutions like Metal Industries Company (MIC) in Trinidad have the necessary machinery and materials to manufacture full prototypes of student projects.

Stronger intellectual property protections – It is very costly to protect the intellectual property rights of new technologies but also necessary to guard against theft and duplication.

Project exhibitions – To generate interest in innovative projects, potential users have to know they exist. Projects featured in exhibitions in the past have been given a positive reception by potential buyers in the food and manufacturing industries.

Field laboratories – The UWI can show the value of its agro-processing innovation projects as well as contribute to the welfare of rural agricultural communities by setting up small preparation and processing field units.

|