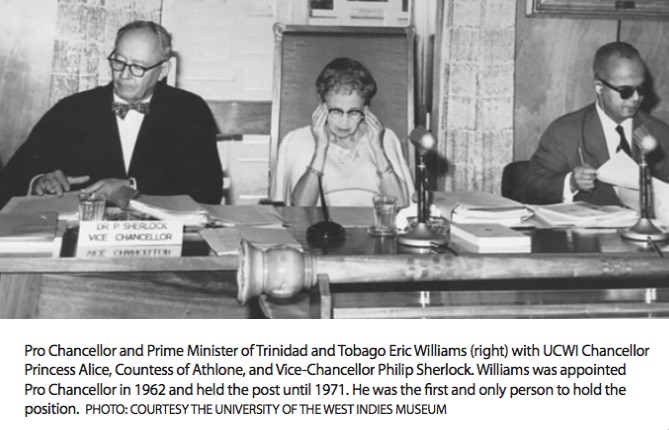

Eric Eustace Williams, the only Pro Chancellor to date of The University of the West Indies, consummate historian and head of the government of Trinidad and Tobago for a quarter of a century until his death in office in 1981, was pivotal in the establishment of a “British West Indian university”.

As far back as May 1944, when the British appointed a commission/committee to examine higher education in their colonies, Eric Williams gave evidence before it in Washington:

“I prepared my notes very carefully. They advocated an independent, unitary, non-residential university working closely with the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture in Trinidad, with a modified tutorial system and a two-year compulsory course for all freshmen, paying particular attention to history, education, agricultural education, social work and the training of civil servants.” 1

On the basis of the above, Eric Williams submitted a far-ranging memorandum to the committee and to the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission (AACC – an agency launched by the US, Britain, France, and the Netherlands to deal with socio-economic issues in the region):

“to study the historical development of university education in the world, with particular reference to colonial or former colonial areas, and in this context, and against the background of primary and secondary education in the West Indies, to propose a university to suit the needs and aspirations of their people… I unearthed a vast literature of commissions and committees which I studied relating to Britain, the Dominions and the colonies. I obtained information on the Hebrew University of Jerusalem from its American Friends in New York and on the University of Puerto Rico. I studied the report of the League of Nations Mission of Educational Experts on the Reorganization of Education in China in 1931... I took as my examples the incorporation of Newcastle units into Durham University, the duplication of university facilities at professional level in New Zealand and South Africa... I rigidly opposed the idea of affiliation to a foreign university, taking as my principal witness the nationalist movement in Ceylon and its opposition to external London examinations. I leaned heavily for this on what the Royal Commission on university education in London... had advised London University in 1913 – to abandon ‘once and for all the pernicious theory underlying its present practice that the kind of education it thinks best for its own students must be the best for all people who owe allegiance to the British flag.’ 2

“The AACC was not impressed: ‘...in general he goes too far too fast. Wants human material to run, swim, and fly before it can walk. Sights set too high.’” 3

Williams circulated his memorandum widely. He made his case everywhere, even to scholars in the field of education in Cuba. He wrote an article on the subject in Spanish for Ultra entitled, “Una Universidad and Las Antillas Britanicas” (July 1944); in the Negro History Bulletin (January 1945); the Harvard Educational Review (May 1945); in School and Society (1946); and another, The Provision of Education for the Natives in Dependent Territories in America, while he was at the Caribbean Commission. He lectured to the Queen's Royal College Literary Society in Trinidad (April 1944); conducted a seminar at Atlanta University (April 1-3, 1946) on “The Idea of a British West Indian University”; and gave another address entitled, The Importance of Adult Education in the West Indies (August 8, 1949). As late as 1978, he was still writing about Higher Education Alternatives in Developing Countries.

Even James Irvine, Chairman of the Committee on Higher Education in the Colonies, informed Williams that in “approaching the problem from a different angle, we have come to the decisions which are not far removed from your own” (April 17, 1945).

With Irvine’s concurrence, therefore, the memorandum was expanded into his book, Education in the British West Indies (1950), the foreword for which was written by John Dewey, one of the foremost scholars on education reform in the US. As Williams stated, though, the book “... differs profoundly both in objectives and in concrete proposals from the recommendations of the Commission..." (November 16, 1945).

Eric Williams visited McGill University (Canada) at the invitation of the British West Indian Society, comprising mostly students. The visit coincided with the Society's conference on “Education in the West Indies”. He subsequently writes that his “major concern is that the breach in the British West Indian Society” involving East Indian students “must be healed” (April 16, 1945).

By May, Williams was weighing accepting the Howard University full professorship he was offered, bypassing the rank of associate professor, as opposed to continuing in his position on the Research Council of the AACC. He indicates that “for the last thirteen years I have striven towards the ultimate goal of being associated with a West Indian University” (May 28, 1945).

Advised of the formation of the West Indian Students Union in the UK, he accepted their invitation to become an honorary member, encouraging them to be a more dynamic organisation than their counterparts at Howard and McGill Universities. He requested their assistance in publicising his book, indicating that the “one dominant idea” motivating his scholarship is “that it is imperative to begin here and now the task of developing an indigenous West Indian culture” (June 27, 1946).

Eric Williams’s aspirations for a British West Indian university were partially achieved in 1948 in Jamaica as The University College of the West Indies, affiliated with the University of London. The “College” became an independent entity in 1962, as The University of the West Indies.

In 1957, however, he took on the US and British governments over the latter’s agreement in 1941 to lease Chaguaramas (a peninsula in Trinidad) to the Americans for 99 years under the Destroyers for Bases Agreement, without the concurrence of the then Governor and his Executive Council. He demanded that the US return Chaguaramas to the people of Trinidad and Tobago as the site of the soon-to-be inaugurated West Indies Federation. The negotiations continued for years and, eventually, the US ceded, but not without the now Prime Minister first extracting from them economic assistance to the tune of some US$30m for local projects, one of which was the College of Arts and Sciences at UWI, St Augustine.

According to Prof Harry O Phelps in the Faculty of Engineering, “The Americans agreed to fund the construction of the building of the Arts [and Sciences] as a form of compensation. They would have never done it if Eric Williams did not demonstrate forcefully.”4

In 1960, the St Augustine campus was established, commencing with the Faculty of Agriculture – the successor to the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture. That same year at St Augustine saw the formation of the Faculty of Engineering, including the Departments of Mechanical, Civil, Electrical, and Chemical Engineering, and a degree programme in sugar technology. According to Prof Clement Sankat, former Dean of the Faculty, “That was a very visionary act of the university which was still a fledgling institution with one campus in Mona, and when the Faculty of Engineering was started in 1960 for the whole university... it had the support of the Government of Trinidad and Tobago and that of the late Prime Minister, Dr Eric Williams”.

The Faculty was established “to serve the business and industrial sectors of the Caribbean”... to consolidate a vision of how development in Trinidad and Tobago was to be achieved, and “to try to create the human resources to meet that development”. 5

This brings us to 1962 and Eric Williams’s visit to Switzerland for, among other topics of mutual interest, discussions with the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva. As a result of the lengthy talks and his direct interventions, UWI’s Institute of International Relations opened its doors in 1966 with seed money from the Swiss Government, which provided assistance to newly-independent countries in the Third World. The UWI Institute, initially administered by Swiss directors/scholars, was mandated to train future leaders and diplomats from the Caribbean. A creative outgrowth of this postgraduate school, an idea that originated with Williams and was thus approved by the Ministry of Education, was a pilot programme that commenced in 1970-1971, whereby UWI lecturers taught the rudiments of international relations in public schools.

In 1966, he persuaded Indian Prime Minister Jawarhalal Nehru to endow a UWI Chair of Indian Studies. Over the decades, this has become a pre-eminent international posting for Indian scholars, with fierce competition vying for the privilege. In 2012, UWI, along with the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR), broadened this in the introduction of now two ICCR Chairs of Hindi and Indian Studies at the St Augustine campus.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the financial support of the Government to the Faculty of Engineering increased even further when Williams, along with the faculty… and The UWI, “engaged in a programme for the expansion of the Faculty of Engineering”. This was directly due to the oil windfall the country was enjoying, which was used to launch downstream petrochemical industries that would benefit the entire Caribbean.

The faculty was enhanced with the addition of Industrial Engineering, Agricultural Engineering, and Petroleum Engineering. Graduate level programmes were also developed: MSc in Construction Engineering and Management, Production Engineering and Management, Petroleum and Food Technology, Power Systems, Teacher Training in Industrial Arts, and Electronics and Instrumentation.

An entirely new Department of Surveying and Land Information was also initiated, as was the Department of Chemical Engineering, “all in support of an industrial thrust in the country, oil, gas, manufacturing, utilities, etc. So, I want to say... as someone who has grown up in the Faculty of Engineering, I want to give the Government of Trinidad and Tobago a lot of credit for the foresight shown... The late Prime Minister must be congratulated for that vision...” 6

As a result of a feasibility study on extending the original UWI Faculty of Medicine at Mona, in 1979 the Government of Trinidad and Tobago also agreed to underwrite the construction of the Mt Hope Medical Sciences Complex – to house a multidisciplinary UWI St Augustine Faculty of Medical Sciences (including a Women’s Hospital) for training in the fields of medicine, dentistry, veterinary science, pharmacology, and advanced nursing.

But there was yet another facet of Williams’s unparalleled focus in 1962 on free secondary education for the new nation’s children, which was soon expanded to free tertiary education and an increase in the awarding of university scholarships abroad.

“[A]lmost simultaneously, Williams implemented a number of measures, which ultimately served to change the face of accountancy...”7 in Trinidad and Tobago.

Prior to his advent on the political scene, and although the British had made an attempt to establish an Accountancy Training Scheme in the early 1950s, the profession was still seen as the purview of “whites”. All of that changed with the establishment of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Trinidad and Tobago (ICATT) in 1970. Its primary goal was to boost the local profession, train and regulate potential practitioners, and obviate the need for UK-based Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) certification. “Thus by 1975, there were 142 professionally qualified accountants...” 8 in the country. Accordingly, “the two elite accounting practices were forced to discontinue their practice on [sic] importing accounting labour...”9.

The 1973 energy crisis, which immeasurably accrued to Trinidad and Tobago’s economic benefit, saw an increased need for accountants to scrutinise the financial operations of the number of state enterprises that the oil “windfall” had occasioned. Williams again turned to UWI, offering significant funds in 1975 for the creation of the MSc Accounting degree.

TThere were, however, innumerable problems between the UWI degree administration and ICATTs membership body, the latter maintaining that the MSc did not meet professional benchmarks. The various disputes, lasting years, even bordered on the suggestion of race as a factor in the clashes.

Regardless, Eric Williams had done his job. What others chose to do with it, was their own burden.

In summary, the passion and persistence with which Eric Williams consistently, and over the decades, used his scholarship and powers of persuasion to advocate for the establishment of a British West Indian university is without equal.

As Ronald Noel states in his paper, Dr Eric E. Williams and Expansion of the University of the West Indies Faculty of Engineering, 1960-1985, and that can easily be attributed to all of the foregoing aspects of the emergent UWI, “The reports and files perused to obtain the scope and purpose of this expansion project did not overwhelmingly identify the Prime Minister by name but the terms ‘Government’ and ‘Cabinet’ were used to refer to various organs of state. It is obvious that he [Eric Williams] led the Cabinet in [sic] which the various reports referred. This is not to say that the Prime Minister was not mentioned in another archive. However... the reflections of the distinguished oral sources confirmed the ambitions of Dr Eric Williams in specific terms and in a general working framework. Collectively they represented the vision of the Prime Minister’s Cabinet and more so an aspect of [his political party’s] policy on tertiary education… It is not unreasonable to deduce that Dr Eric Eustace Williams believed in the vision of the technocrats and academicians at The UWI or [that] they bought into his vision of an eminently industrialised Trinidad and Tobago...” 10 and, by extension, the Caribbean region.

1 Eric Eustace Williams, Inward Hunger: The Education of a Prime Minister (Markus Wiener Publishers, 2017), 96.

2 Eric Eustace Williams, Inward Hunger: The Education of a Prime Minister (Markus Wiener Publishers, 2017), 97-98.

3 Eric Eustace Williams, Inward Hunger: The Education of a Prime Minister (Markus Wiener Publishers, 2017), 98- 99.

4 Ronald Noel, Dr Eric E Williams and the Expansion of the University of the West Indies Faculty of Engineering, 1960-1985: A Report on the Legacy of Dr Eric Eustace Williams in the Department of Engineering (Port of Spain: For the Eric Williams Memorial Collection, 2009), 13.

5 Ibid., 17-18

6 Ibid., 19-20. Ronald Noel interview with Prof Clement Sankat, October 2, 2009.

7 Marcia Annisette, The Colour of Accountancy: Examining the Salience of Race in a Professionalisation Project

8 Braithwaite (1980)

9 Marcia Annisette, The Colour of Accountancy: Examining the Salience of Race in a Professionalisation Project

10 Ibid., 46-47.