This year, we celebrate the 50th anniversary of CARICOM – the intergovernmental body established to unify the Caribbean region of the 1960s and 70s. For the then newly independent territories and those seeking independence – underdeveloped, small and lacking resources – joining forces was a strategy of survival.

CARICOM came into being as a replacement for the Caribbean Free Trade Agreement (CARIFTA), which existed from 1968 to 1972, and whose role was to promote trade among the region’s English-speaking territories. Wanting to strengthen the region, as well as create a common market, the Caribbean’s Commonwealth leaders, Prime Ministers Errol Barrow, Forbes Burnham, Michael Manley, and Dr Eric Williams, gathered at the Seventh Heads of Government Conference in 1972, and voted to transform CARIFTA into CARICOM’s initial incarnation – the Caribbean Community and Common Market. CARICOM was officially established with the signing of the Treaty of Chaguaramas on August 1, 1973, and had four member states – Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago.

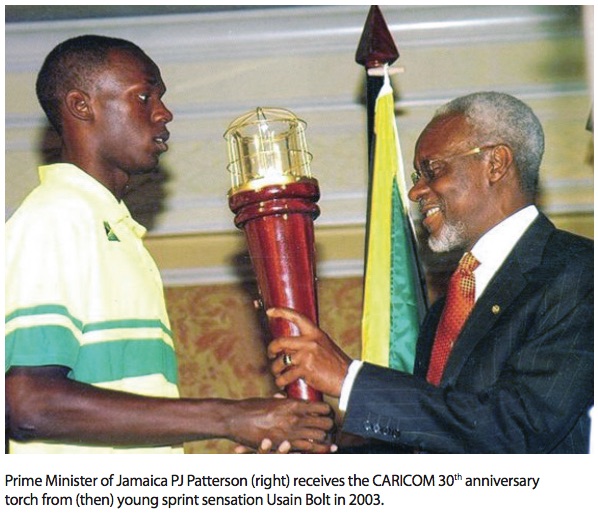

LEADERS COMMEMORATING A CARIBBEAN MOMENT: The region’s heads of state in 1983 at the ceremony for the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the Caribbean Community in Chaguaramas, Trinidad. Standing from left are Prime Minister (PM) of Grenada Maurice Bishop, PM of Belize George Price, (then) Deputy PM of Antigua and Barbuda Lester Bird, Prime Minister of St Vincent and the Grenadines Milton Cato, PM of Barbados JG “Tom” Adams, PM of the Bahamas Lynden Pindling, PM of St Kitts and Nevis Kennedy Simmonds, and the PM of Saint Lucia John Compton. Seated, from left are PM of Dominica Eugenia Charles, President of Guyana Forbes Burnham, PM of Trinidad and Tobago George Chambers, Secretary-General of CARICOM Dr Kurleigh King, PM of Jamaica Edward Seaga, and Chief Minister of Montserrat John Osbourne. PHOTOS: COURTESY OF THE CARICOM SECRETARIAT

Dr Jaqueline Laguardia Martinez, Senior Lecturer at The UWI’s Institute of International Relations (IIR), explains that the Caribbean of the 1960s and 70s was not only underdeveloped, but faced a structural challenge.

The small sizes of the Caribbean territories meant that they faced many constraints. “Because if you have a limited size, you will have limitations related to the condition of small states”, from natural resources to economic resources which both affect possibilities for infrastructure, as well as the nation’s capacity to diversify its economy.

With “open economies’ integration” at its root, CARICOM was created to surpass the limitations experienced by the region’s newly independent nations. Not only did the body promote intra-regional trade, it aimed to forge tighter economic linkages by expanding the market and building economies of scale.

The individual nations’ small populations meant their businesses had limited markets so it was very difficult for them to survive, Dr Laguardia Martinez explains. The establishment of CARICOM would lead to a market increase - a larger population to which produce could be sold, a better environment for investments and manufacture throughout the region, as well as easier job creation and access to resources.

Other pillars under CARICOM’s action plans for its member states – which grew to include 10 more territories as the region developed – were the promotion of “functional cooperation” within the region, as well as “coordination in foreign affairs”. The idea, Dr Laguardia Martinez says, was that “in unity there could be major strength”, because a very small country could easily be overlooked “in multilateral fora”, but an entity with 14 votes “can actually make a difference”.

In 2002, Haiti joined CARICOM, making the organisation 15 member states strong, a number which still stands today. Dr Laguardia Martinez adds that CARICOM also includes five associate member states which, “are not independent nations and, therefore, do not have the capacity of designing treaties as fully constituted independent nations.” Rather, they are associated with the body and so “are also involved to a certain extent and participate in some of the CARICOM activities”. Montserrat, she says, is the only exception in that, though it is a dependent territory, it is a CARICOM member.

Part of CARICOM’s purpose, says Dr Laguardia Martinez, is to achieve regional consensus in foreign policy “and try to advance a single Caribbean position that can give [our individual countries] a better opportunity to be a voice…be involved, and have an influence on international affairs”.

Yet another pillar under the CARICOM mandate is security, both in terms of disaster management - how we “keep people safe when we are facing an extreme meteorological event” - and crime.

Crime, Dr Laguardia Martinez says, is “a major issue”, particularly because of our location in “a very vulnerable space” for activity like the illicit trade of drugs, arms and people. And, she notes, “islands have very porous borders”, so coordination and continuous conversation are essential for securing the region.

CARICOM’s mandates are seen by some as heavy and complicated. Yet, strides have been made for the region. “CARICOM can show major achievements in terms of the coordination of foreign policy and functional cooperation,” Dr Laguardia Martinez asserts.

To her, the body’s biggest impact comes from its network of regional agencies, each of which has its own area of expertise, for example, disaster management, cooperation, health and education. These agencies, she says, “allow not only regional conversation, but regional norms”. She shares one of CARICOM’s more recent successes – its efforts to establish regional protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic.

She shared another example: “We have CARICOM engaging in conversations with the United States [and] the European Union, [so] it is not about a single country relying on the bilateral diplomatic relation. They also have a regional [presence]...as a group, and have more leverage when trying to advance certain positions.”

When we look at education, she says, CARICOM is heavily involved in the region’s “unified education policy”, including the exams, and of course, The University of the West Indies.

In fact, “UWI is one of CARICOM’s major achievements,” says Dr Laguardia Martinez, education being indispensable in producing the level of knowledge excellence, innovation, and productivity required to push the Caribbean forward, and drive the integration that would help the region not only to survive, but thrive in a complex world.

The UWI shares 2023 as a milestone year with CARICOM, is The UWI, turning 75 this year and who investigated the feasibility of the idea of Caribbean integration when it first took hold within the region in 1965. UWI has since been a platform from which CARICOM’s efforts within the region have been hailed and interrogated.

However, CARICOM is not without its challenges, among which are the economic integration of the region and the full adoption of the Caribbean Single Market Economy, established in 2006.

“This is quite contradictory,” Dr Laguardia Martinez says, “because CARICOM was created to achieve economic integration.”

She acknowledges, however, that there are many barriers to this, “most of them related to the removal of goods, services, capital and, especially, workers”. Other challenges include the body’s “capacity to connect with Caribbean people”, she says, because “A lot of people in the Caribbean are totally unaware of CARICOM. They have no idea what their regional institution is doing and its service to the region.”

This celebration of CARICOM’s 50th anniversary, she says, is essential, both to mark such a momentous occasion and to raise public awareness and understanding of the institution which still holds so much potential for the development and prosperity of the region.