|

|

|

|

May 2018 |

Home to relics from our country’s rich history, the National Museum holds objects time-weathered but tangible, and the atmosphere inside the Victorian-era building, with its narrow corridors, dim lighting and wood floors, immerses visitors in the journey through our nation’s past. Enter the DCFA’s exhibition, however, and the museum’s rustic environment gives way to light and space. The room’s high ceiling and white walls make it feel open and the art is well-spaced, giving each piece its deserved attention. Unlike the museum’s artefacts, protected behind glass cases, preserved for essential historical and cultural record, the DCFA students’ art pieces are exposed to engage the senses and encourage interaction. Rather than represent fact, they’re meant to share the artist’s experience and to invite the viewer’s interpretation. Yet, these students’ works of art are an apt accompaniment to the history that lies in our museum. Continuing our country’s story, they share experiences of the modern world, from the emotions attached to abuse and mental illness, to the practical needs for proper facilities in public spaces and a serious solution to our crime problem.

A walk around the gallery shows a variety of media (sculpture, assemblage, weaving, photographic and graphic, for example), created using a multitude of different materials (from red sand, wood and glass, to soap and fabric) that invite reflection. Elements of the dark and macabre arose as artists tackled issues of mental and physical illness. Curtis Thomas’ resin and lace sculpture, aptly titled “Undone,” illustrated the fragility of the human psyche in the face of depression. Cheryl Wight’s “Redemption,” a large, flowing, tangle of bright red cloth and thread, went further, inviting the viewer to walk through the 12-foot high, 63-foot wide mass. The inability to see clearly through the fabric from either side is meant to depict the isolation and confusion of dementia, as well as the distress of a caregiver.

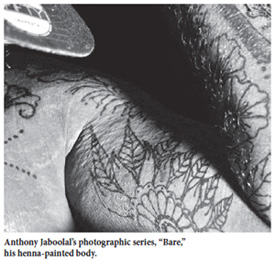

Cultural gender stereotypes and body image issues were investigated in Anthony Jaboolal’s photographic series, “Bare,” which depicted shots of his own henna-painted body. The close-up images, zooming-in tightly on each body part, and the reflective effect of black and white photography, conjured a deep sense of intimacy, giving the audience an exclusive view into the highly personal struggle with insecurity. Design student, Kadine Antoine, approached the all-too prevalent human obsession with appearance, by illuminating the eating disorders and self-harm practiced by many young girls. Covered in happy shades of pink and calming blues, with hand-painted images of open-winged dragonflies and butterflies, and hand-written messages of inspiration throughout its pages, her journal, the “Battimamzelle Activity Book,” offered a creative outlet through which sufferers could channel their emotions and eliminate destructive behaviour.

Rainy-day clothing, a chair for DCFA students, a short animated film, and various explorations of nature, religion, illusion, sound, smell and texture … the DCFA’s final-year student art exhibition was filled with artistic pieces, too many to describe, but each unique and impactful. |

UWI’s final-year Visual Arts students added a flair for the contemporary to the Trinidad and Tobago National Museum and Art Gallery this April. With its largely conceptual theme, the Department of Creative and Festival Arts’ 2018 Degree Student Exhibition, served as both complement and contrast to its venue.

UWI’s final-year Visual Arts students added a flair for the contemporary to the Trinidad and Tobago National Museum and Art Gallery this April. With its largely conceptual theme, the Department of Creative and Festival Arts’ 2018 Degree Student Exhibition, served as both complement and contrast to its venue.  Keith Cadette, Lecturer and Coordinator of the DCFA’s Visual Arts programme, explains that in creating their pieces for this exhibition, students were “given the opportunity to explore beyond the traditional.” He explains that visitors to the exhibition would not have found “the typical paintings, drawings [and] sculptures that one would normally associate with a local fine art exhibition.” Instead, the artists explore different experiences, using different media.

Keith Cadette, Lecturer and Coordinator of the DCFA’s Visual Arts programme, explains that in creating their pieces for this exhibition, students were “given the opportunity to explore beyond the traditional.” He explains that visitors to the exhibition would not have found “the typical paintings, drawings [and] sculptures that one would normally associate with a local fine art exhibition.” Instead, the artists explore different experiences, using different media.  Sade O’Brien’s “Daddy,” offered its audience a similarly affecting experience of caring for a dying loved one. With bags of ice suspended in mid-air, condensation forming on their surfaces and slowly dripping water into containers filled with red and yellow liquids, coloured to represent bodily fluids, she renders palpable the physical pain of the ailing and the emotional pain of those closest to them.

Sade O’Brien’s “Daddy,” offered its audience a similarly affecting experience of caring for a dying loved one. With bags of ice suspended in mid-air, condensation forming on their surfaces and slowly dripping water into containers filled with red and yellow liquids, coloured to represent bodily fluids, she renders palpable the physical pain of the ailing and the emotional pain of those closest to them.  Brent Bristol’s graphic novel, titled “Ordeal,” was his artistic attempt to raise awareness of crime. With its clean lines and attractive colours, the comic quickly attracted the eye. Its superhero theme and locally-inspired characters – with different skin tones and hair textures, names like “Che” and “Anton,” and dialogue that could only be uttered by a Trinbagonian – seemed designed to give our youth (or any comic book lover) their own superheroes to look up to.

Brent Bristol’s graphic novel, titled “Ordeal,” was his artistic attempt to raise awareness of crime. With its clean lines and attractive colours, the comic quickly attracted the eye. Its superhero theme and locally-inspired characters – with different skin tones and hair textures, names like “Che” and “Anton,” and dialogue that could only be uttered by a Trinbagonian – seemed designed to give our youth (or any comic book lover) their own superheroes to look up to.