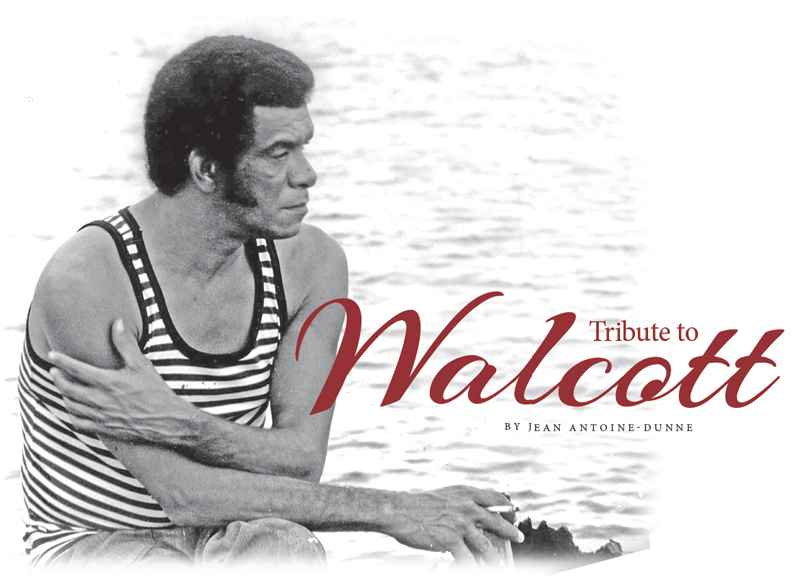

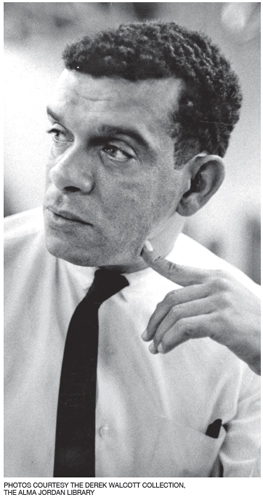

The poet Laureate Derek Walcott who died on March 17, 2017 was from St Lucia, but Trinidad became his other island home shortly after graduating from The UWI, Mona, in 1953.

Trinidad is figured throughout his works, in particular in The Prodigal, which is in many ways a love song to both St Lucia and Santa Cruz where his daughters live. Santa Cruz became in this work a source of images that reflected his intense spiritual relationship to land and to poetry. The immortelle offered a metaphor for heaven and the breadfruit and frangipani became homilies to the beliefs of his people.

Walcott revelled in the use of words and the many double meanings that words have accumulated through their use in the vernacular. He was given to political criticism and had an acerbic wit, in keeping with the tradition of calypso. He ranted at the governments of Trinidad and Tobago and of St Lucia for their treatment of the arts and his condemnation of the rape of Caribbean landscapes by foreign investors and in the name of tourism is well known. He spoke often of the tribulations endured by the Trinidad Theatre Workshop, though there were recurring explosive relations between himself and this flagship company he formed in the fifties. The evening before his funeral Wendell Manwarren paid tribute in a passionate rendition of one of Makak’s speeches from “Dream on Monkey Mountain”. As a performance it demonstrated Walcott’s insistence on remaining true to the Caribbean voice.

Community was of vast importance to him. At the academic celebration of his work hosted by The UWI in 2010, he wept openly. In many ways his response to this Nobel Celebration was an indication of his humility and his understanding of the role of the artist as one who spoke for and on behalf of his people and of the artist as one who was obliged to work hard and shape something new.

In 2015 I asked him whether he had any regrets and his answer was, “I could have been a better writer.” This, from a man who had by then received every honour and acclaim for his poetry, including the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1992. The response lends credence to Professor Emeritus Ken Ramchand’s praise for Walcott as a “supreme example of the joy of plain and simple hard work as well as dedication to a calling, which in his case, occupied over 80 years and with that, a humble awareness that no matter what result and reward you have to believe in it and have to strive always towards the unreachable, unnameable ultima Thule.”

He was a man for whom friendship was sacred. Many of his poems speak of such friendships: with Seamus Heaney, and with Joseph Brodsky, two other poet laureates, for example. But he commemorated so many. His penultimate collection, “White Egrets,” remembers many whose toil he saw as sacred work, including August Wilson, Wilbert Holder and Aimé Cėsaire. But with typical generosity he pays tribute to the living amongst whom he numbered poets, scholars, actors and friends.

Derek was a hard taskmaster, as those who worked with him knew well. But he mentored young poets, including our own graduate Vladimir Lucien. Many of these students visited him in St Lucia and he continued teaching virtually until a short time before his death. At his funeral these students, and poets whose work he had nurtured from St Lucia and elsewhere, and painters such as Jackie Hinkson, lined the aisles in tribute. And it is no small matter that his funeral focused on his relationship with other artists and writers, many of whom like the Trinidadian Robert Antoni were present. Derek was a hard taskmaster, as those who worked with him knew well. But he mentored young poets, including our own graduate Vladimir Lucien. Many of these students visited him in St Lucia and he continued teaching virtually until a short time before his death. At his funeral these students, and poets whose work he had nurtured from St Lucia and elsewhere, and painters such as Jackie Hinkson, lined the aisles in tribute. And it is no small matter that his funeral focused on his relationship with other artists and writers, many of whom like the Trinidadian Robert Antoni were present.

Walcott taught at Boston University after leaving Trinidad, but despite his many departures to different places such as Italy, the “here” and the “elsewhere” of his existence were never about which was better, or of metropolitan privilege, but rather how each echoed “home.” For him privilege resided in his islands.

He later went on to become Professor of Poetry at the University of Essex where he spent several months every year. There he worked with the Lakeside Theatre on the production of “O Starry Starry Night.” In this play, though most clearly expressed in the St Lucian premier, the human body acts as a spatialisation of experience. The body and its occupation of space is the manifestation of desire, trauma and repression. These all appear as the sources of artistic potential and production.

“O Starry Starry Night” pays homage to St Lucian artist, Dunstan St Omer, who died two years ago and as with so many of Derek’s other works, foregrounds the interactive relationship between the arts and his multifaceted talents. Derek was a fine painter and continued painting until almost the end.

His final work in 2016, “Morning, Paramin” was a collaboration between himself and the painter Peter Doig. In a sense it continues in the tradition of “Tiepolo’s Hound” (2000) in which as a painter he meditates on the nature of light and perception. The inclusion of his own paintings in “Tiepolo” engages readers in the debate about the relationship between word and image, but also on the marginalisation of the black in the context of European art.

He wrote essays, many of which have become central to the debate about what constitutes Caribbean art and Caribbean identity. His Nobel speech “The Antilles” has already provided critics and politicians with a language of definition in its imaging of a broken vase:

“Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole. The glue that fits the pieces is the sealing of its original shape. It is such a love that reassembles our African and Asiatic fragments, the cracked heirlooms whose restoration shows its white scars.”

It is significant that for the poet this is “the exact process of the making of poetry, or what should be called not its "’making’ but its remaking”. For Derek Walcott was a supreme craftsman. In “Arkansas Testament” he reflects on the artisan-like process of making poetry. But this craftsmanship was of necessity a quest for an echo of the landscape and the asymmetrical nature of life and art in the Antilles. His perpetual search for such a form led to an apprenticeship to many masters, and evolved over the 70 years of his career. It led to a search for new metaphors that would come from the land and history. So for him the word pommerac represented an historic language bequeathed by the colonisers and also signified a vestigial trace of the Aruac presence and the many layers of trauma that have made the Caribbean the rich repository of culture that it is.

This idea is equally present in his plays. At the rehearsals for Steel, he sought to ensure that the very movement of the Caribbean body and the music of the place would shape the production. He brought into one theatrical space the raga and the dance movements of masqueraders and of Shouter Baptists as part of his ongoing attempt to show Caribbean art as syncretic process and as a meeting of different cultures.

Many of his plays did not receive the same recognition as his poetry, though it might be argued that the stage was his great love. But no one could deny the beauty and the success of “The Joker of Seville,” in particular at its Boston performance. “The Joker” exemplified that unique combination of witty social commentary, sexual innuendo, characterisation and beautiful poetic language all united by music and movement. It is equalled only by “Ti Jean” which has seen many incarnations, finally emerging as “Moon-Child” in 2011.

Walcott also wrote film scripts. Many of these are stored in The UWI and University of Toronto archives, but only two have been produced: “The Rig” and “Haytian Earth.” His work anticipated the now current conversations about the relationship between film, digital and literature.

The long poem, “Omeros,” is filmic in its structure and in this way allows the poet to create a conversation between the major writers of the Caribbean, including Kamau Brathwaite, VS Naipaul and Wilson Harris, whose concept of simultaneity he sought to express through montage. In this work he returns to the debates of the ’60s and ’70s about the importance of Africa. He also pays homage to those influences that he had long acknowledged, from Homer to Yeats and Joyce to Lowell and Chamoiseau. Its multifaceted and polyphonic structure makes it an epic beyond compare.

Derek Walcott’s loss leaves a huge gap that cannot be filled. But his legacy as a man and as an artist remains.

For Professor Emeritus Gordon Rohlehr,

“Walcott was a mega mind, an enormous intellect, which was constantly searching out the pathways we should traverse. He never dabbled but delved deeply into literary imaginaries, into mythic and the folk sensibilities, into the visual as painter and filmmaker, into song as the producer of musicals. Consider for example that our understanding of what he produced would be incomplete until we take into account the over 500 pieces which he wrote on diverse topics in the “Trinidad Guardian” in the six to seven years he spent as a journalist there.”

Walcott’s life and work transcend simple assessments. It is this sense of a complex intervention into the nature of Caribbean art and the sensibilities of the region and his project of giving voice to this multiplicity that may well be viewed as his most enduring gift to the Caribbean.

Dr Jean Antoine-Dunne is a Walcott specialist and recently retired as a Senior Lecturer in Literatures in English and Film at the St Augustine campus. Her book Derek Walcott’s Love Affair with Film, published by Peepal Tree Press, is due out in October. |