As he opened his notebook, I was struck by the neat, cursive, rounded script. That single page communicated to me a fastidious, organized, serious character. Though I am no hand-writing expert, my impressions were confirmed in the conversation that followed.

After 14 years, Sir George Alleyne officially ended his role as Chancellor of The UWI, making way for the new Chancellor, Mr. Robert Bermudez, who assumed the position on July 16. With ten days left before he demitted the office he has held since 2003, Sir George sat down to answer some questions I had outlined to him beforehand – and that’s how I saw his notes.

Sir George has had a distinguished career in medicine: as practitioner, as academic, as administrator and policy maker. He will turn 85 in October and as a staff member observed, he is “disturbingly spry.” He has held leadership positions in the world’s most influential health bodies: the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization. Before becoming Chancellor, he was Director, and when he became Chancellor they made him a Director Emeritus. Recognition for his services to medicine had come in 1990 with a knighthood, and in 2001 with the Order of the Caribbean Community, why did he step outside of the ‘healthy’ world?

“If you went to university at the time I did you would never lose the love for the university. It probably is the same way now. I can tell you those persons who were at my time at the university; we became West Indianized at the university. People of my generation at the university developed a deep and abiding feeling for the institution. So in a way I never really left the institution,” he said, as he made the absurdity of my question delicately clear.

“Who could refuse being Chancellor of one’s university?”

Given that the statutes of The UWI do not explicitly define the Chancellor’s role, and that each university has its own, I asked him to outline what it has meant to him.

“I took the trouble of looking up a paper that had been put to [University] Council about some of the roles at the institution. I can’t tell you that I would have followed them all, but there are certain ones that stood out and were probably more important for me than others” he said.

“The number one is leadership. You are the titular head of the university and you have to project a positive image of the institution in all you say or do, in various fora,” he said, adding that it was also important to stress its regional nature.

“The one they pointed out as number one about projecting a positive image of the university is terribly important to me and that’s the one I have been acutely conscious of over 14 years and I tried to do.”

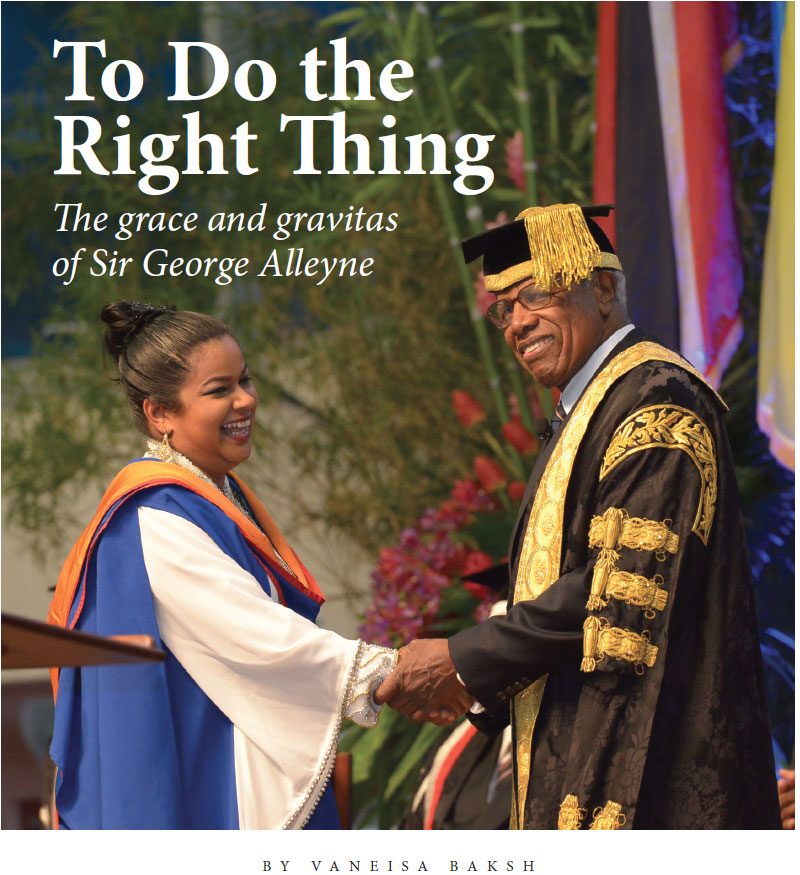

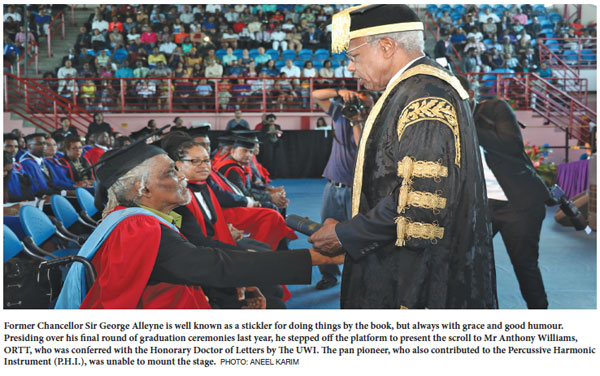

The image of Sir George, resplendent in his robes, solemnly shaking each graduate’s hand and saying “Congratulations,” and the special “Well done, well done, my sincere congratulations,” for first-class honours, is an integral part of each graduation ceremony. He does not deviate. It is his assigned role to preside over ceremonial functions, the Council meetings, the graduation ceremonies.

“People would say that is ritualistic; and I agree. Well I happen to like rituals… We all have personal rituals. Family rituals help to bind families together and I think that institutional rituals help to bind institutions together. Rituals also tend to embody principles. For example at graduation, I pay a lot of attention to the format of the ritual because I think that rituals done sloppily are worse than no rituals at all. I pay a lot of attention to the seriousness of my greeting. It is not a flippant matter… I am all in favour of the joy and exultation of the moment, but I believe that unruly behaviour disturbs the beauty of the ritual,” he said. It is not simply being old-fashioned. “You are saluting the individual candidate. I took that very seriously because I thought if a person has gone through the institution, to be received into the company of those who have passed through the institution before, I think that is a very important part.” “People would say that is ritualistic; and I agree. Well I happen to like rituals… We all have personal rituals. Family rituals help to bind families together and I think that institutional rituals help to bind institutions together. Rituals also tend to embody principles. For example at graduation, I pay a lot of attention to the format of the ritual because I think that rituals done sloppily are worse than no rituals at all. I pay a lot of attention to the seriousness of my greeting. It is not a flippant matter… I am all in favour of the joy and exultation of the moment, but I believe that unruly behaviour disturbs the beauty of the ritual,” he said. It is not simply being old-fashioned. “You are saluting the individual candidate. I took that very seriously because I thought if a person has gone through the institution, to be received into the company of those who have passed through the institution before, I think that is a very important part.”

Students think so too. In the annual graduation survey, when asked, “Please indicate your #1 graduation memory,” the answer is repeatedly “shaking the Chancellor’s hand while crossing the stage.”

Presiding over the University Council meetings is another of the roles of the Chancellor. As much as he likes ritual, he is not there as an ordained adornment. He takes copious notes and meticulously checks minutes to ensure accuracy.

“I know that some people believe that minutes should be as skeletal as possible, should record the simple decisions that were taken. I take it differently. I say that in 50 years’ time when people look back they should be able to see what happened at Council. They need to have some idea of the thinking behind the decisions,” he said.

Another of his roles as described by the Council was “ensuring that the institution remains a regional institution,” he said.

“When I became Chancellor it was ten years after the previous Chancellor [Sir Shridath Ramphal] had established a committee on the governance of the institution. I thought it was an appropriate time to have another committee, so I got a team of five or six of us to look at the governance,” he said, and their first task was defining it.

“We defined it as those structures and processes and traditional practices necessary for the optimal functioning of the institution,” and they went about revising some of them.

“One of the things that struck me in the context of the regionality of the institution was in the views of at least two of the heads of government. They put the case to me quite forcibly – unless the institution establishes a more credible and visible presence in all of the contributing territories, the university will cease to be relevant. And it would cease to be a genuine regional institution.

“At the time we put forward the view that the university would look to abolish the term ‘non-campus territories’ and we advocated that it should be called a fourth campus. It became the Open Campus,” he said.

He feels that was a good move.

“The main thing out of that of which I am particularly pleased is the idea of a more visible presence in every one of the contributing territories, and the idea of them coming together under one. I am pleased to be part of the genesis of that idea,” he said.

While the University’s brand as a regional institution remains strong, the increased autonomy of each campus and the reduction in the movement of students among campuses have diminished the “West Indianizing” experience that shaped earlier alumni. Despite its claim, does he think the University actually functions as one entity?

“I have agonized about this. You have to think about what you lose and what you gain. There is no doubt that The UWI could not retain its function as a small, elitist campus in Mona. It could not retain its function. [Sir] Arthur Lewis was very clear on that; the massification of education had to be the route to go. And once you take that route, it is inevitable you lose that closeness that comes from a small campus where everyone lives together.”

Even though the intimacy has practically gone, he has still found evidence of regional spirit, citing a paper presented by students to the Council a few years ago asking that the WI be put back into UWI. “That was what the students themselves were articulating for: more West Indianness in the institution,” he said, and it is expressed as well at graduation time.

“I have sat and listened to valedictorians at all our graduations and when you hear some of the valedictorians speak, still speak, of the extent to which it is a West Indian experience, it really does my heart good.”

In spite of the spread, he said the experience of the students in their formative years is “leading a lot of them toward the belief that they belong to a regional entity.”

“So I applaud the effort of the present Vice-Chancellor when he says there is one UWI, and I point out that we have always had one UWI, so how I interpret that initiative is to make some of the structures, the processes to facilitate the oneness – cause you’re not creating one university, there’s never been anything but a one university – but I make the point that you are trying to create the structures that will facilitate that oneness. That is how I have interpreted this initiative which is being put forward. And I am all in favour of having structures and processes in place that will facilitate this oneness of the institution.”

One of the concerns about educational institutions is that the focus is on certification and students do not demonstrate the kind of civic-mindedness so vital for the development of the region. Sir George feels that by the time students enter The UWI, their characteristics are already formed by their environments and culture, and it would be tough to reshape them radically. One of the concerns about educational institutions is that the focus is on certification and students do not demonstrate the kind of civic-mindedness so vital for the development of the region. Sir George feels that by the time students enter The UWI, their characteristics are already formed by their environments and culture, and it would be tough to reshape them radically.

“That is very difficult,” he said, “Yet we cannot dissociate ourselves from the responsibility to try to inculcate some of the values that would lead to a better citizen.”

He has heard many good reports about graduates, particularly from his medical community, and he stoutly defends the quality of the students generally.

“I’ve heard the comment being made on many occasions about our graduates not being job-ready when they come out. I think that is absolute nonsense. I say no graduate will ever be job-ready. None. What we hope is that they will be job-prepared, to have the basic skills, attitude, competence to adapt to the job they’re going to do.

Every good employer has a responsibility to help the person who comes in to adjust.

I believe this is something we should push back hard on,” he says indignantly.

It is a measure of how strongly he feels because he is characteristically unflappable.

As we wound up, I asked him what he thought was his legacy, and his response was immediate and emphatic.

“I shall never answer that. You know why? Because I always believe it is arrogance to say that you leave a legacy. It is for other people to say what they think of what you’ve contributed. I think it is pompous arrogance. My legacy is so and so. I never answer that. No one ever does anything alone. If I say I am pleased to have contributed, and I use the word contributed, because you could not do it unless you have support.”

It was the position he took in a speech he gave at Mona in 2005, which he called Listen to the Chimes of the Bell, where he celebrated the growing number of students coming from the poorer stratum of the society as a sign that “we have moved from being the university of the elite to become the university of the many.”

And he threw out a question, and offered an observation.

“How do we maintain excellence and at the same time, increase access? I have found that there is remarkable commonality in the requisites for personal and institutional excellence. There is self-discipline, the capacity to listen and hear, and avoid the sinister hubris. Perhaps the most difficult is the capacity for honest self-criticism, the acknowledgement that you can and will be wrong often and the understanding that the seal of excellence is never given by one’s self.”

They are words that resonate with wisdom and grace – the mark of a man who has done The UWI the honour of being its Chancellor.

Vaneisa Baksh is editor of UWI TODAY. |