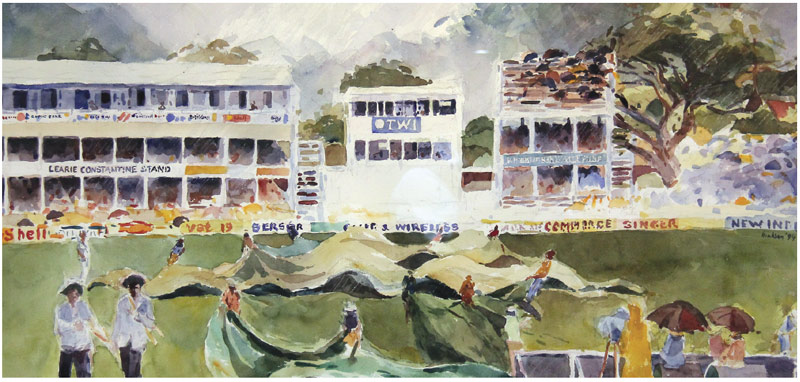

This watercolour called, “Rain Stop Play” by Jackie Hinkson is part of the Angostura collection of around 100 works of art on the walls of its corporate offices. Angostura graciously allowed us to reproduce this piece after Mr Hinkson generously agreed not only to share it, but to also permit us to reproduce some of the cricket sketches he has done over the years.

We have selected sketches that express the mood that regional cricket seems to have found itself in. There is a sense of waiting and watching, hoping that something different will happen, but hardly expecting that it will. So the figures in the sketches do not exude the tension of anticipation, rather they look mainly like patient die-hards, hardly knowing what else to do with themselves.

The watercolour above that shows the covers going on to stop play, seems symbolic of the endless rainy season of West Indies cricket.

At its best, Test cricket is about thought, technique and time. Waltzing to a rhythm of spikes and lulls, lunges and retreats, and often, long spells that invite languor rather than tension; it is not for the impatient – neither onlooker nor player.

It calls for time – the most expensive commodity these days– and few have it to spare. And like a majestic leatherback turtle in a world buzzing with batimamzelles, it is losing ground quickly and within this century will likely take its place among the extinct.

A dread prophecy, to be sure, but such is the evolutionary way.

We do not wish to simply wallow in mourning; but to discuss its features, as they are expressions of the conditions under which our lives are unfurling. In this issue, we hope to simultaneously discuss West Indian society and West Indian cricket, choosing our moment to coincide with the annual general meeting of the West Indies Cricket Board on March 7 and the ongoing ICC Cricket World Cup, eight years after it was held here on our shores.

We would like to question the ownership and control of West Indies cricket. We look at the issue of leadership, and how the region has fared under its sloppy hands. We look at a future that sees cricket primarily in the formats of the one-day matches of 50 overs, and the three hours of T20 games. What has been the impact on our cricket; what about the four-day games?

The popularity of ODIs and T20s is intricately bound to two prevailing factors: time and entertainment. The packages wrapped up with shiny, gaudy ribbons that cater for TV rights, feteing crowds, high performance fees and roving cricketers offer much more to suit the modern appetite.

And it is all propped up by time. Five days are just too many for the average person to take in a game. With ten Test teams, half of whom are hardly worth watching, it has become increasingly difficult to draw crowds. It is my belief that the magnetism that West Indies cricket once held was a powerful life force for Test cricket. That the decline in Test cricket coincides with the decline in West Indies cricket is no coincidence. The world would have been far more inclined to loiter on Test grounds had West Indies cricket continued in all its magnificence.

Time campaigns on no one’s behalf; and the shorter forms of the longer form of the game are wresting its premiership away. Even if we acknowledge that, how are we preparing for the future?

We would like to think we are opening a regional discussion on the future of cricket and of our region; one that is not raging with animus, but one that retains its composure despite the atrocities that have been perpetrated unchecked for far too long. For we have to look closely at the roles we have played in condoning a state of affairs that bodes well for none of us.

In this 21st century of moving and shaking, apathy is not how we can play the game.

This entire cricket excerpt can be viewed in PDF format here, or read online in the following articles:

|