“I never attended university,” he says.

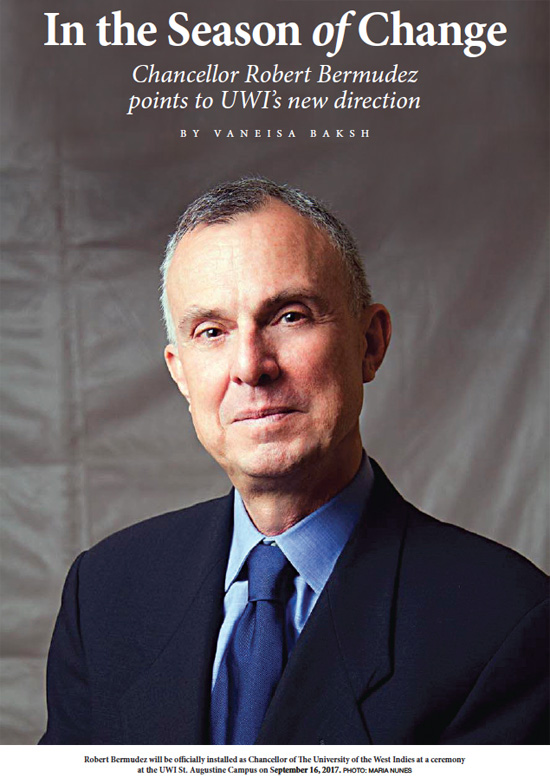

It is a statement that might alarm those academics who have grumbled about the selection of Robert Bermudez as sixth Chancellor of The UWI as he is not one of them.

It is true that he is not an academic, but spend a little time in conversation with this Chancellor and you will conclude that he is an intellectual.

People often use the words ‘academic’ and ‘intellectual’ interchangeably, but they are not quite the same.

The Oxford Dictionary defines an academic as “a teacher or scholar in a university or college,” and one of its descriptions (I mischievously add) is: “not related to a real or practical situation and therefore irrelevant.”

It also defines the intellect as the “faculty of reasoning and understanding objectively,” and an intellectual as “a person with a highly developed intellect.” It follows that an academic may not necessarily be an intellectual, just as an intellectual may not be an academic.

Either way, Mr. Bermudez, a businessman, has entered the UWI world of academia at a time when it has declared its intention to think differently, and his selection as Chancellor is an indication of where it wants to go.

He is aware of the consternation, but is not fazed.

“People equate education with attending a university,” he says, acknowledging the value of mass education, “but some people are privileged to get educated one-on-one by people who are experts in the field, and that was the opportunity I had.”

He credits his achievements to the lessons he had from members of the business community.

“Those guys taught me stuff, and by the time Tony Sabga was finished with me, I always said I had a PhD because he was the best that I ever had the good fortune to know.”

He says those periods of mentorship provided him with multiple perspectives and that “gave me a huge advantage.” He points out that the support of staff, “who come out to work every day and do extraordinary things,” was an important part of the Bermudez success story.

He refers to the concept of apprenticeship, which he says is part of the Costa Rican culture, so that people say “I was made by,” to indicate who had been their mentor. It had seemed an odd segue into the Cost Rican university system, but later, I realized he would have been fairly familiar with the country because more than a decade ago, he started the company, Alimentos Bermudez S.A., which is based there. It explains why he favours their delicious coffee.

While Chancellor Bermudez expressed many views on The UWI’s culture and where he thinks the institution should go, he is actually very reticent about his personal side. He doesn’t talk about himself, nor does he offer details on his range of business relationships. He has never been interviewed.

“I am a private person,” he says repeatedly, and it took some doing for him to be persuaded that people should know something about the man who would be Chancellor.

So, who is Robert Bermudez?

He is the son of Margot and Alfredo Bermudez; delivered by a midwife at a maternity house on Dere Street in Port of Spain on April 21, 1953. His family lived in St. Ann’s then, but he has spent most of his years living in and around Port of Spain.

“All my life, even to this day, I can hear the Queen’s Royal College bells ringing,” he says. “So I think I’ve spent most of my life within earshot of that.”

After attending the primary school run by a “lady named Mrs. Bodkins on Oxford Street,” he went to St. Mary’s College, where they also had a prep school.

He insists he was a terrible, hard-headed student. (I get the impression that he was probably another bright, bored child afflicted by an education system that had not yet learned how to teach them.)

“I was not a good student. I did not enjoy my school years. I didn’t enjoy the academic part of it. I sure enjoyed being at St. Mary’s. It was fun. You had lots of friends. You had a lot of things to do.”

He said he played sports but was “useless.”

“I was not a sportsman of any quality. I played cricket, terribly. I played tennis; something I thoroughly enjoyed. I played a lot of tennis in my life. I played it poorly, but I had a lot of fun,” he says laughingly. “But the academic part… my whole ambition in life was not to come last, because my mother quarreled so much. I kept my mother as quiet as possible by staying away from last place.”

His mother was very strict, he says, a disciplinarian, who kept an eagle eye on his hard-headedness. His only brother, Bernardo, is nine years older, “so effectively, we were two only children,” and it meant he was often caught in his mother’s crosshairs.

At 16, after St. Mary’s College, he was sent to St. George’s College in Surrey, England, a boarding school founded in 1869 by a Belgium Catholic order of priests called the Josephites. He does not talk about that period; but in 1973, he returned to Trinidad and began working at the Bermudez Biscuit Company.

The company had been started by Venezuelan brothers, Jose Rafael and Jose Angel nearly a century ago, opposite St. Mary’s College on Park Street. His father, Alfredo, along with his brother joined their uncle, Jose Rafael, in making the salt biscuits (known as water crackers), that would become the famous Crix brand.

The building burned in the 1950s and this was when the company moved to Mt Lambert where it has grown and flourished.

He started off as a route supervisor, visiting customers in his assigned sector to ensure they were being serviced and eventually learning his way around the country. “There is no place in Trinidad that I do not know,” he says. “I cannot get lost anywhere because our customers are everywhere. As far as we are concerned, once you open your door to do business, we will come and supply you. It is part of the values of our business.”

He did a bit of everything in those days, learning the business thoroughly (he particularly likes the manufacturing process) and in 1982, when his father died, he assumed full responsibility for the business.

The Bermudez name was already in every household locally; but it wasn’t so much what he got, as what he made of it. In no time it had gone international: its website says the Group has “more than 3000 employees spread across the Americas.”

The Group comprises Kiss Baking Company, Jamaica Biscuit Company Limited, Holiday Snacks Limited, West India Biscuit Company Limited, Bermudez Biscuit Company and Alimentos Bermudez S.A. These six companies are located in Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, Barbados and Costa Rica, but their distribution is regional and includes the USA, Canada and the UK.

He is also Board Chairman at Massy Holdings Limited.

After 44 years, he is a reputable and respected figure within the business community. He has been a director on the board of 18 different organizations throughout the region – banking, brewing, insurance, tourism, packaging, distribution, retailing, air travel, even matches – quite the gamut; and if you consider his latest portfolio, you can add education to the list.

Does this make Chancellor Bermudez a mogul, a tycoon… a magnate? They are words that invoke power, wealth and influence, but even if he has all of these, somehow those descriptions do not sit immaculately on his neat frame. Those words cast a decadent, maybe even ruthless, shadow; and there is something too light about him for them to fit snugly. He has a clear distaste for trappings and fanfare, and an unobtrusive manner that suggests he prefers to observe than to be seen.

He likes walking, hiking and riding his bicycle, and spending time with friends. “I think my favourite pastime might be having nothing to do,” he says with a laugh.

Throughout our conversations some words come up repeatedly – values, service, mentoring, collaboration, equity, opportunity, balance, commitment, fun, optimism… When he articulates his views on the University, on the region’s development, on the young people in our midst, each idea is rooted inside one of those words. He is not spouting platitudes; he is earnest, and has done his homework with the care of a man who believes in the importance of attention to detail.

His manner is informal – a spectrum away from the preponderance of protocols that define the University – but he seems thorough, keen to understand things, and interested in learning. He might be a breath of fresh air to the many intellectual academics at the University.

When asked what challenges he sees for the University, he goes right back to its first incarnation as the University College of the West Indies in 1948 and the hurdles it faced.

The rate of change now will test the University’s agility, because the changes are so great that they are “disrupting the structures that we have come to depend on and understand,” he says, and “it is a problem it will have to grapple with for the rest of its existence.” The strategic plan has to be dynamic, “because it is a five-year plan and before the five years are over, the changing environment is going to force adjustment as things we don’t foresee begin to happen.”

It used to be straightforward, he says, “you went to a university and you got a set of tools, and basically, for the rest of your life, you used those tools.” With technology rendering everything obsolete in no time at all, today’s world requires lifelong learning and universities must be prepared to provide programmes that upgrade skills continuously, he says, and that creates an opportunity for them to earn revenue as well.

But even as he identifies several kinds of collaborations the University can build – with States, students, the private sector – for income generation, he believes it must not forget its main responsibility.

“The reality is that the University is not a business and that although there are business aspects to the University and there are things about business that could be useful for the University to think about, the University cannot be approached as a business, because it is not here to make a profit, it is here as a common good.”

That places a special burden of care on the University in the way it manages its resources. “Every contributing country has scrimped and saved to meet its obligations, and we have to make sure that we use the funds wisely,” he says.

Equity is important, he says. “The University must be focused on creating an equitable environment. The history of these islands – slavery, indentureship, colonialism, – this is a University that, more than most, must be focused on providing an equitable environment. The University has only just adopted a gender policy in the year 2017, and a gender policy is only the beginning of an equitable environment.”

He thinks the University should create a forum for debates; that faculty members should share their expert opinions on matters of public importance, and that they should encourage students to do the same.

“The UWI must have a balanced view, showing different arguments, so people can draw their conclusions. You don’t want to have a politicized university; it should provide a forum for discussion and the students must be an important part of that,” he says.

“We have to serve the community; that is the basic purpose of the University in all the things it does, whether it is research, teaching… the University has to become more and more integrated into the community.”

This is one of the ways he sees the collaborations working.

“We have a responsibility to ensure that once we educate our people that we provide them with opportunities, otherwise we are going to create a cadre of dissatisfied, unhappy young people who cannot fulfill their potential,” he says. The “we” he is referring to is “the community, the West Indies,” he says.

“That requires collaboration on every front and it something that is happening already. People are leaving university and can’t find the kind of employment they expected to find with a university degree.”

He focuses very heavily on the quality of a student’s experience, and I wonder if, because his own experience was unpleasant, he has greater empathy for the nature of the learning environment. To him, it should not simply be a matter of certification, but that the University has to help nurture their sense of belonging and pride in being West Indian.

“The more the University can be integrated, the more West Indians can come on the campuses and get to know each other, the stronger the glue that holds Caricom together,” he says.

Does he think the regional movement is failing?

“I don’t think so. I think that over the years we’ve had our quarrels, but this is not unique to Caricom. We’ve had our disagreements but all in all, I think there is a genuine understanding that we are stronger together. There is no doubt of it. Even our largest islands are relatively small and if we don’t stick together and try to achieve some size in unity, then I think we will be the worse off for it.”

He talks about how his travels throughout the islands have made him appreciate the beauty of each.

“I like all of them. Every country in the West Indies is fun. I can’t say that there is anything in any of them that I don’t enjoy. And they are so different. You would think we are homogeneous. We are not, in that we have our own quirks and you just have to appreciate them for what they are,” he says.

True of the islands. True of the people.

Vaneisa Baksh is Editor of UWI TODAY. |