News Releases

Visual Communication on the Road with Hinkson in 2021 and Beyond

For Release Upon Receipt - February 22, 2021

St. Augustine

The following article is issued on behalf of Godfrey Steele, Professor of Human Communication Studies in the Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Education, at The University of the West Indies (The UWI) St. Augustine Campus.

Making art accessible and preserving it has always been a concern for many civilisations. A concern met in many Old World places, it remains a familiar challenge for us in the New World, but is not without solutions. It is also a concern for Jackie Hinkson, brought to life through the artist’s imagination in his exhibition of murals and sculpture, On the Road. This, in a place where, as Walcott says, the poet (or the artist/painter/musician) has no nation but imagination. It is also a concern for the general public interested in seeing and living beyond the mundane.

Without benefactors, opportunities to access art would be fewer or would neither exist now nor beyond COVID-19 and its variants. So how does one access art? One response is to be as imaginative as our artists. Hinkson’s On the Road is such a response.

Asked to reflect on the exhibition, Hinkson stated that he was “stunned by the public reaction”, adding that he did not expect it. For him the experience was “most astonishing” as he recalled seeing “families with children… people you might never see in an exhibition… a range of ages… and [their] enthusiasm about the whole thing.”

Just down the street from the Savannah, Parliament and Mille Fleurs and around the corner from Curepe, Chaguanas and Chaguaramas, and San Fernando, Point Fortin and Moruga, and across the water from the House of Assembly, Hinkson continues. He continues to create, remake and recreate each year, continually presenting and revitalising images that appear jaded to the casual observer. He achieves this with life-size still lifes and scaled-up versions of ourselves and our inescapable urban landscapes and escarpments on the street, savannah and life stage of murals. Standing tall like Lovelace’s warriors, they feature Hinkson’s green dragon, as evocative as the one that can’t dance, a vagrant human figure and a hound that is as emblematic as Tiepolo’s.

The street-located museum on Fisher Avenue in St Anns, originally planned for February 5-14, ran till the 16th. Some work is over ten years old, extended, retouched or updated to incorporate topical issues, but all are contemporary, bold, intuitive and insightful. His work is never on hold or inquorate like other business in the society. He presses on, the careful gardener I interviewed in 2011.

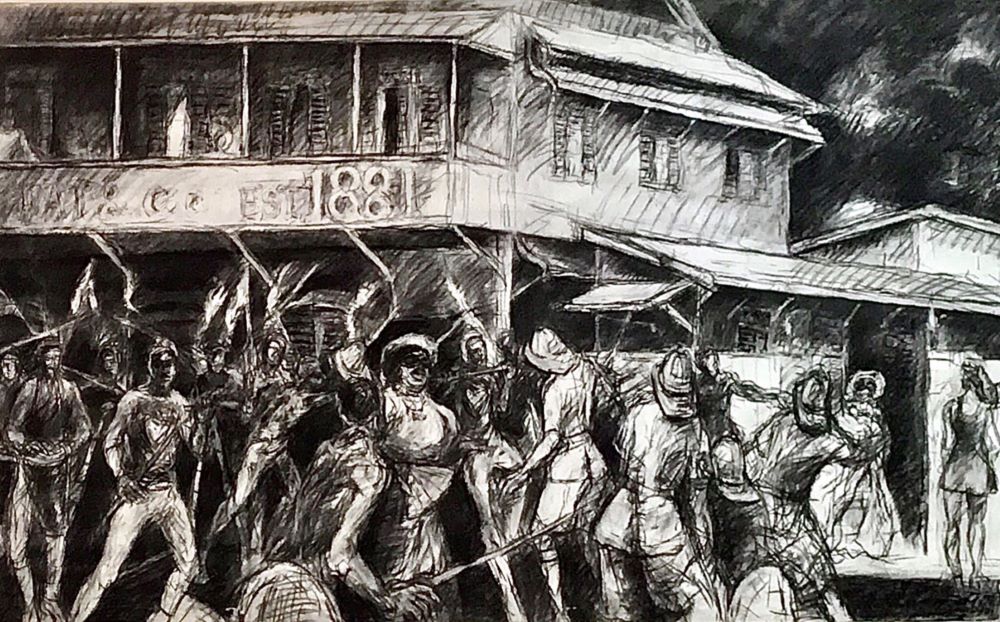

On the Road was set up along both sides of the lower end of Fisher Avenue with neighbourhood cooperation when community can mean connecting, even while socially distancing. Perhaps more than ever, the exhibition illustrates the making of connections, whether in mas or masquerade, despite the distancing ravages of our times. These ravages include political, social, health and cultural topics, but Hinkson’s work does not merely reproduce commercial logos, protest placards and signs of the times displayed in murals presented on 4x8 or 8½ foot panels, one as long as 105 feet. Some are connected physically and thematically as in “Band of the Year”. Images seep from one panel to another, through combinations of crayons, oils, acrylics on canvas and large prints of charcoal on wood and metal frame on vinyl, and sculpture. “From Canboulay to Beyoncé”, with enlarged charcoal prints, is separated physically for practical reasons and located at opposite ends of the neighbourhood art promenade, but what you see in one location resonates in the other.

The exhibition also features previous wood sculpture. The accomplished plein air watercolourist who is committed to a vision beyond the space of four walls, and who has also worked in oils and conté crayon and charcoal drawings for well over 50 years, has not only been working outdoors but has been taking his work outdoors for more than two decades. He displayed sculpture outdoors in “If You Say So” (Soft Box Studios, 2011), in “Evolving” (Vicky Assevero’s Kiskadee Gallery, 1999), Port of Spain and other work at Queen’s Hall, and the Department of Creative and Festival Arts and Alma Jordan Library at The UWI, St Augustine.

Yet the Caribbean plein air artist, Hinkson, is different from Homer as explained by Timothy Wilcox, an expert on English watercolours, at “Retrospective” at the Art Society in 2017, also featuring Hinkson’s book “The Light in Paint: 50 Years of Watercolours”. Like unaccommodated man in Shakespeare’s King Lear, art is sometimes unfortunately not well accommodated in the Tropics, but people make space for it in their hearts and minds and blood. As Walcott’s “Spoiler’s Return” reminds us, Hinkson is composing still, compos mentis, despite the decay and death everywhere.

Hinkson’s bold communication through art initiative was not supported in any large measure by corporate or state agencies, except for bpTT, although he and other artists may have benefitted more in the past. Even in these understandably difficult times, the lack of support, funding, ideas or interest in supporting art cannot be explained. And that support is not required in monetary terms. But money always helps, especially when it is tax deductible. There are many spaces on the grounds and in hallways of the Parliament buildings, at NAPA North and South, and large state and private buildings, and gaping spaces that can be also used.

Some newer and future buildings need to be created with permanent spaces for art, mas, pan and other music in the architecture of the built environment, not as an appendage or temporary space. No doubt Hinkson’s work is widely known, and his generosity more so as he continues to be available to scores of students, young artists, colleagues and the curious. Daily, 4:00-6:00 pm officially, but not rigidly, Hinkson was on his feet talking about his work at Fisher Avenue during the exhibition ended February 16.

Hinkson uses social media, emails and websites to talk about and make his work accessible in a novel way on a large scale for Trinidad and Tobago. This generosity is not without a human cost or some risk, especially when large public gatherings are not possible or safe. Visible safety and distancing measures are made. Whether or not there is a permanent place for the work of Hinkson and other artists, that goes beyond singular, disconnected and outdated museum spaces, this is not an issue for him. He soldiers on, on the road, putting in long hours, days, months and years. It would be good if Hinkson and other deserving artists, were to have a home other than, in his case, his home and that of accommodating neighbours and the goodwill of family, friends and well-wishers.

The invigorating and free walk along Fisher Avenue, where Hinkson’s vale of imaginative work allows us to savour the Carnival flavours, sights and sounds, in a seemingly silent and shapeless time, is memorable. It is memorable, despite the mindless cacophony that is often headlined with the frenzy of news production and reporting on the viral commodities of crime, gender-based violence, political trysts and duels, fallen statues and traditions, permanent and mutant epidemics, budget and fiscal issues and refinery sales and fossil fuels and feuds, misinformation and infodemics, mistrust and fake everything, fake sou sou, and zesser parties. These are all images and themes in Hinkson’s murals, each competing for freedom of expression and space in the Trinidad and Tobago psyche. To the media’s credit, despite press deadlines and fewer resources, this exhibition was publicised. It reflects, perhaps too, a continuing recognition of the value of Hinkson’s work in these times, and over the years.

Amid this frenzy and noise, it helps the sense and the soul to be able to step back, or walk or drive by Hinkson’s On the Road. Take your smartphone, snap the onsite QR code (courtesy son David and grandson Liam) and visit YouTube to see and hear Hinkson speak to you briefly to introduce the exhibition and a few pieces. In his words, Hinkson does not seek to explain or analyse his work or his pieces but seeks to intuitively and impressionistically share his imagination with you, allowing you to respond in your own way. With Hinkson’s help one cannot help engaging in introspection, analysis and critique even if he does not overtly set out to do so and tell you what to think. Like all agenda-setting communication, Hinkson’s art does not tell you what to think, but highlights images and themes, drawing the eye and the viewer in, and appealing to other senses. He does so using composition techniques to juxtapose shapes and symbolise ideas and emotions (Hinkson, 2017, p. 73).

He captures and directs light and shade, and through selective emphasis and aesthetic sentience his art inevitably tells you what to think about, and perhaps, sense in your own way.

You might also think you are in one of those galleries famous elsewhere, using rented or free headphones paid for by support for the arts. But you can’t travel there and you don’t need them now, because here is where you are. Here On the Road, as Destra and Machel remind us, “Carnival in T and T is so special to all of we/Like we need blood in our veins/That’s how we feel about Port of Spain.” Here you can have this live experience and take away a visual, permanently archived personal and social media memory, which also belongs in a virtual Collection of Digital Museums of the Caribbean when there is no Carnival or Panorama or while Kitchener’s Carnival is Over for this year.

END

Note to the Editor

Captions:

Photo 1: A colour panel depicting the effects of life during COVID-19.

Photo 2: A panel from the exhibition in charcoal.

Photo 3: A lone (socially distant) masquerader in front of the exhibit.

About The UWI

For more than 70 years The University of the West Indies (The UWI) has provided service and leadership to the Caribbean region and wider world. The UWI evolved from a university college of London in Jamaica with 33 medical students in 1948 to an internationally respected, regional university with near 50,000 students across five campuses: Cave Hill in Barbados; Five Islands in Antigua and Barbuda; Mona in Jamaica, St. Augustine in Trinidad and Tobago; and an Open Campus. Times Higher Education has ranked The UWI among the top 1,258 universities in world for 2019, and the 40 best universities in its Latin America Rankings for 2018 and 2019. The UWI is the only Caribbean-based university to make the prestigious lists.

As part of its robust globalization agenda, The UWI has established partnering centres with universities in North America, Latin America, Asia, and Africa including the State University of New York (SUNY)-UWI Center for Leadership and Sustainable Development; the Canada-Caribbean Studies Institute with Brock University; the Strategic Alliance for Hemispheric Development with Universidad de los Andes (UNIANDES); The UWI-China Institute of Information Technology, the University of Lagos (UNILAG)-UWI Institute of African and Diaspora Studies and the Institute for Global African Affairs with the University of Johannesburg (UJ). The UWI offers over 800 certificate, diploma, undergraduate and postgraduate degree options in Food & Agriculture, Engineering, Humanities & Education, Law, Medical Sciences, Science & Technology, Social Sciences and Sport. As the region’s premier research academy, The UWI’s foremost objective is driving the growth and development of the regional economy. For more, visit www.uwi.edu.

(Please note that the proper name of the university is The University of the West Indies, inclusive of “The”)

Contact

Marketing and Communications Department

- Tel.: (868)-662-2002 ext.2013/2014

- Email: marketing.communications@sta.uwi.edu