If this were a Netflix documentary, we would open on a rustic village scene of Indian descent. A peasant farmer would be yoking a buffalo to a wooden cart, while chickens would be briskly pecking at the dry, patchy grass underfoot. Two half-clad children would peer shyly out from the doorway as their father climbs onto the cart and trundles off to another back-breaking day in the field. If this were a Netflix documentary, we would open on a rustic village scene of Indian descent. A peasant farmer would be yoking a buffalo to a wooden cart, while chickens would be briskly pecking at the dry, patchy grass underfoot. Two half-clad children would peer shyly out from the doorway as their father climbs onto the cart and trundles off to another back-breaking day in the field.

We would be taken on a journey from India to Trinidad, replete with breathtaking vistas of hundreds of acres of land with water buffalo of varying hues and horns grazing languidly. We’d be taken through industrial plants where Buffalypso hides are being transformed into leather; to fancy restaurants where the lean, red loins are being served as a preferred beef substitute; to roadside stalls where fiercely marinated strips would be sizzling on grills and topped with imaginative Trini sauces; we would be watching celebrity chefs on TV rhapsodizing about the mozzarella cheese that has to be made from Buffalypso milk. Oh! And what are they saying about paneer and kulfi? You’d be salivating when you hear.

But this is neither a Netflix documentary, nor is it a success story. In fact, it might qualify as the worst case of Trinidad and Tobago missing out on something that was created here that has been so undernourished as an industry that it might just have made itself extinct, while several countries have developed something rich and viable from the Buffalypso they imported from local pastures.

If that sounds like the story of the steelpan, it is simply the same pattern, except that the steelpan has a whole lot of life in it, and will survive, and maybe even prosper.

In this sad tale, a once vibrant collective herd of roughly 6,000-8,000 water buffalo has been dramatically whittled, mainly by the dreadful Brucellosis infection, but exacerbated by neglect and a lack of resources.

It is a story that began with the vision of a veterinarian, Dr. Steve Bennett, who saw the potential for a meat industry to be developed by refining the breeds of water buffalo that had come from India. (See The Journey of the Buffalypso.) Once the strain that he joyfully named Buffalypso came into being, the possibilities opened up.

The meat was not beef, though it had a similar taste – thus making it permissible for Hindus to eat it – and it was leaner and less marbled, making it healthier. Buffalo milk had been embraced as the basis of the popular Mozzarella cheese in Italy and other European countries, and was a staple in the production of Indian products, such as paneer, kulfi, yoghurt, ghee, and sweets like barfi, rasgulla and rasmalai.

The hide was as thick as an elephant’s making them particularly resistant to ticks, which are the plague of cattle, but also lending itself to particularly durable leather that was well suited for furniture.

To cream it off, the germplasm from this superior breed of the water buffalo could be the basis of an exclusive line of cattle exports. In fact, a 2007 report in the Italian Journal of Animal Science, stated that the Buffalypso had been exported to 19 countries , including the USA, Colombia, Cuba, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico (via Honduras), Nicaragua, Panama, and Venezuela. The industries in those places have moved forward profitably.

With all of this, who would not be tempted to invest in opening up a buffalypso industry?

The State was, or so it said.

The 2012-2015 Action Plan for the Ministry of Food Production, Land and Marine Affairs (still posted on the site for the Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Fisheries, so I assume it is still The Plan) has this section:

Buffalypso/Buffalo

Facilitate the development of the Buffalypso meat industry.

Conservation of the genetic material of the Buffalypso through the development of a gene bank and development of herd registry and herd book.

Facilitate the development of the Buffalo milk industry.

Continue to maintain the bio-security of the Aripo Livestock buffalo herd.

Implement a management program for Brucellosis with a view to eradication.

So far, so good. If all goes according to plan, it sounds like a heap of positive things. Except for the timeline.

That’s the twist in the plot.

In 1998, twenty years ago, Brucellosis, a dreaded cattle infection, was detected within the buffalypso community and everything changed.

In April 2017, a status report on the water buffalo industry was published in “Tropical Agriculture (Trinidad)”. Its aim, said one of the authors, Riyadh Mohammed, was to try to get a grasp of the size, location and state of the water buffalo in T&T. Based on surveys done in 2012, the data tell a story, best repeated in their words.

“A test and slaughter brucellosis eradication programme, instituted by the Government, resulted in the three large WB (water buffalo) producers selling their stock and closing their WB production operations. Based on annual reports, 3255 WB were slaughtered due to a positive brucellosis status from 1998 to 2008.”

Those figures were taken from the Ministry’s report for 1999-2009.

The researchers noted that in 1999, the Animal Health Division tried limited vaccination with RB51 – a commercially available vaccine in the USA that had had some success with bison – but it did not protect the WB.

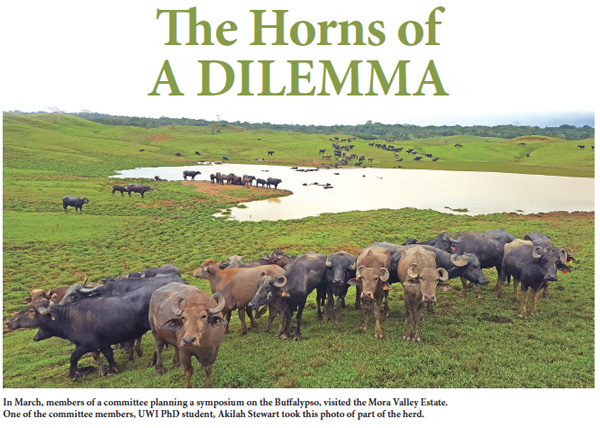

The infected herd was confined to the 1657-acre Mora Valley Estate in Rio Claro in 2003. A 2015 Ministry of Food Production Project Document, prepared by a Mora Valley Steering Committee, noted that the main operations were “cocoa production and water buffalo rearing but in 2003, operations on the cocoa estate ceased and some of the animals were sold/left abandoned.”

The document goes on, “The estate was to be restocked by 2006/7 but this did not materialize. The livestock farm was originally 1400 acres, but some of the land was distributed to ex-Caroni (1975) Ltd employees in 2008/9 while some was divested into MFP large farm in 2012/13.”

Using figures from the status report, the State owned 1021 head of Buffalypso in 2012, and the majority were infected with Brucellosis at a rate that has not decreased over 20 years. Plans to develop a Buffalypso industry have never materialized. There are only a few of the ‘pure’ Buffalypso remaining at the Aripo Livestock Station – an entire germplasm can be lost.

Despite numerous representations on the potential for a Buffalypso milk industry – based on the high butterfat content of the milk – nothing has ever been done to establish even facilities for this. I was told that because it is not classified as milk, it cannot legally be sold as such.

The infected herd at Mora Valley has literally gone wild, a feral bunch that roams the vast acreage, fending for themselves and not accountable to anyone (except for Deolal, the single keeper who can walk among them). Nobody can accurately tell the size of the herd, or how many are infected with Brucellosis, or whether they have strayed off the premises.

People who once kept herds have given up, mainly because there has been little support for Buffalypso as either a meat or dairy industry.

It is truly another sorry tale of neglect.

If this were a Netflix documentary, it would have taken us on a long journey full of promise, potential, and magnificent vistas along the way, but as the shadows lengthen, the cameras would pan in on that one man on his Buffalypso cart, returning home, dusty, bedraggled and hungry, with nothing to show for his day of hard labour in the fields of misfortune. And the sun would set innocuously behind his back. |