EIGHTY-SEVEN BILLION US DOLLARS – that’s how much market research firm, Global Market Insights, says the global commercial seaweed industry will be worth by 2024. Seaweed as food, as biofuel, in agriculture, textile manufacturing, pharmaceutical production, and even cosmetics, it has many profitable uses. China, Indonesia, South Korea and Japan dominate the industry, which produces over six million tonnes of seaweed per year. But it’s not enough to meet world demand. In this market, Indonesia has been increasing its seaweed production by 30 percent per year. EIGHTY-SEVEN BILLION US DOLLARS – that’s how much market research firm, Global Market Insights, says the global commercial seaweed industry will be worth by 2024. Seaweed as food, as biofuel, in agriculture, textile manufacturing, pharmaceutical production, and even cosmetics, it has many profitable uses. China, Indonesia, South Korea and Japan dominate the industry, which produces over six million tonnes of seaweed per year. But it’s not enough to meet world demand. In this market, Indonesia has been increasing its seaweed production by 30 percent per year.

Seaweed is an asset. For years it’s been invading the coasts of the Caribbean, piling up on beaches, patiently waiting for those with the capacity to recognise it for what it is – opportunity.

“It is a gift,” says Professor Jayaraj Jayaraman, Professor of Biotechnology and Plant Microbiology at the Department of Life Sciences at St. Augustine’s Faculty of Science and Technology.

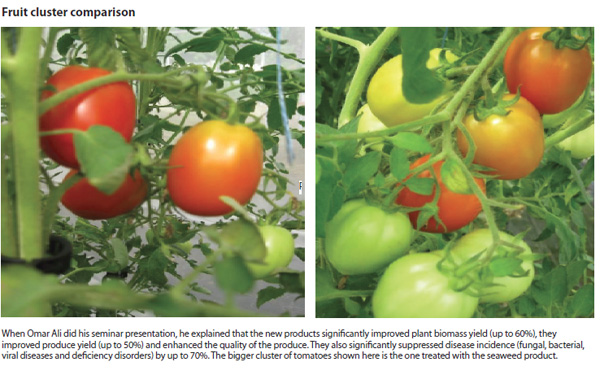

The Professor is one of the driving forces behind a tight team of researchers, among them Omar Ali, a graduate student focused on tropical seaweeds. Omar, whose work was first highlighted in UWI Today in 2017 (https://sta.uwi.edu/uwitoday/archive/june_2017/article19.asp), has achieved outstanding results using seaweed as a biostimulant for agricultural crops. When applied to tomato and sweet pepper plants, extracts from three local seaweeds produced incredible growth and disease resistance, far better results than that of commercially available biostimulant products.

“It increased the yield and product quality very significantly,” says Omar, speaking of the extract’s effects. “It also reduced disease levels significantly compared to the controls. By this way we can cut down chemical use to one third or even more.”

The three seaweed types (one red, one brown and one green) were used as the basis for products that increased plant size by up to 60 percent, improved yield up to 60 percent and suppressed disease by up to 70 percent compared to the locally available commercial biostimulants. “Our current focus is only on those abundant ones; but there are few more rare seaweed species which we have discovered are better than the best reported anywhere in the world. But I’m careful not to tell you about those now,” laughs Prof. Jayaraman.

“I was skeptical at first about the idea of using seaweed as a biostimulant,” says Dr. Adesh Ramsubhag, Head of the Department of Life Sciences, but when they showed me these results, I felt this is the best way to go. We vowed to thoroughly study the mechanisms and roll out a product for crop use.”

The research team is justifiably excited. They have created products with a level of performance that surpasses what the imported alternatives offer. And they say it will cost much less.

“About 40 to 50 percent less, and that is a conservative estimate,” says Professor Jayaraman. “The main raw material is free. It is waiting there on the shore.”

At their lab in the Natural Sciences building, Omar and Professor Jayaraman show samples of the commercially available biostimulants on the local market. One is made up almost completely of chemicals. The other two are branded as seaweed stimulants. The first lists seaweed as a 10 percent proportion of its ingredients; the second, five percent. The other ingredients include humic acid, nitrogen phosphate, zinc, chemicals and more chemicals.

“It’s like an energy drink. It will give a short-term boost,” Jayaraman says. “What we are offering is like a nutritious meal. It has a long-term stabilizing effect.”

The team’s seaweed products contain at least 50 percent seaweed-based ingredients. The team’s seaweed products contain at least 50 percent seaweed-based ingredients.

“It’s natural and organic,” Omar says.

The idea of using seaweed as a biostimulant is not new. In North America, Ascophyllum, a brown seaweed native to temperate climates, has been used for some time for crop growth and health. In fact, Professor Jayaraman has worked with an Ascophyllum-based biostimulant manufacturers in Canada for more than 10 years. It was based on this experience that he recognised the potential for tropical seaweeds. The UWI team’s research is not reinventing the wheel. It is making the wheel with local materials. “Local seaweeds are a bit tougher species though, but we found better ways to derive a premium product which is as good or even better than what you see imported from the Americas and Europe”.

“He knew the potential of those temperate types but no one had done a lot of hard scientific work on the tropical species,” Dr. Ramsubhag says.

The initial research was carried out by graduate student Antonio Ramkissoon, who is also doing landmark work on microbial-based products with high potential for pharmaceutical use (see https://sta.uwi.edu/uwitoday/archive/april_2018/article11.asp). When they saw the results, it was decided they needed a researcher dedicated to seaweed. It was a role Omar accepted.

“It is impactful research,” says the 24-year-old from Indian Walk in Moruga. “We are working to get a premium product out of it, not just writing papers, graduating and leaving.”

Omar says he wants to both see the creation of a new company manufacturing their seaweed products and encourage organic farming practices. “Some parts of the work are of intellectual property value, and my mentors are already working on it,” he says.

A big part of their research includes field trials with local farmers, and they have been happy with both the products’ organic nature and the bigger and better yields they produce.

But much more needs to be done – more field trials and more data collection, specifically more detailed basic studies, including genomic and transcriptomic sequencing to determine what processes are taking place and what genes are being affected when the seaweed extracts interact with the plants. Also the environmental effects of these extracts need to be studied.

“We have to use the science to drive the product development process, “says Dr. Ramsubhag. “We can’t just collect seaweed, make a little concoction, that might sometimes work and most times not.” “We have to use the science to drive the product development process, “says Dr. Ramsubhag. “We can’t just collect seaweed, make a little concoction, that might sometimes work and most times not.”

And research, particularly the sequencing, is very expensive. The research team has done outstanding work funded by earlier (now discontinued) external grants, private sources and even directly out of the pockets of Ramsubhag and Jayaraman. The Life Sciences students have also shown great commitment to the work, volunteering their time and effort for little to no recompense. Moving forward, with these strong results, they are hoping for more support.

“We don’t need millions of dollars. We can start small,” says Professor Jayaraman. “But we must not wait too long. We cannot wait for things to happen. We have to make them happen.” “Extracts are only a part of the story. There are many exciting molecules which are of high commercial value. We are also working on those with the help of our colleague, Dr. Nigel Jalsa from the Chemistry Department,” says Professor Jayaraman.

Dr. Ramsubhag agrees. “In the business world, time is of the essence.” But he remains optimistic that they can find support for their work. “The end we have in sight is the creation of a UWI spin-off company. But there are several models we can look at. We can even licence the product and work with the private sector.”

“Adesh is more of an optimist than me. He is a mahatma,” says Jayaraman, smiling. Having a long career as a researcher in both India and North America, he has the firsthand knowledge of how aggressively societies invest and pursue high potential research.

“I am more cautiously optimistic,” he says.

Meanwhile the seaweed piles up, mountains of it, on the Caribbean coasts.

How big is seaweed? It’s big enough for a segment on “60 Minutes”, the renowned US news programme. “A promising source of food, jobs and help cleaning ocean waters,” is how journalist Lesley Stahl describes it in the July 15 news segment. How big is seaweed? It’s big enough for a segment on “60 Minutes”, the renowned US news programme. “A promising source of food, jobs and help cleaning ocean waters,” is how journalist Lesley Stahl describes it in the July 15 news segment.

The growing demand for seaweed is easy to understand. It’s a natural product in the age of increased health consciousness and environmental sustainability. And it has many, many uses. Seaweed has traditionally been a source of food as well as a food additive and that still remains its primary use, with an estimated 80 percent targeted towards food consumption in 2015. Seaweed is categorised by colour: red, green and brown.

Asia is both the main producer and market for seaweed food products. China and Indonesia are the major producers. Japan, South Korea and China are the major consumers. Europe has been steadily increasing its seaweed consumption, with the UK as the top market. But seaweed is enjoyed around the world as an ingredient in food items as varied as Welch bread to Caribbean punch.

Beyond food, seaweed has myriad uses, and even more are being investigated. Seaweed is a source of hydrocolloids, gelatinous substances that are very useful for a variety of purposes. The hydrocolloids are alginate, agar and carrageenan. They are used as natural food additives and preservatives, in natural medicine and science, filtration (of unwanted nutrients in water such as ammonia), crop biostimulants, ingredients in paint, toothpaste, cosmetics, and feed for livestock and fish.

Conservative estimates put the current value of the industry at between US$10 billion and US$16 billion. With such a variety of uses and growing demand it is easy to see why. |