|

December 2009

Issue Home >>

|

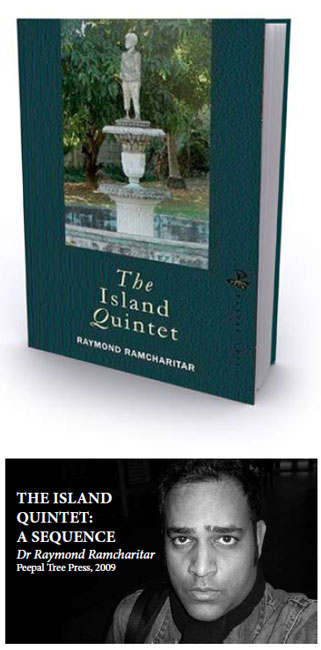

Glimpses of a vista Glimpses of a vista

by Louis Regis

Raymond Ramcharitar’s collection of stories is described in the blurb as having “a truth-telling honesty that does not disguise the compassion of a writer for whom the island still means a good deal.” Even before this, the blurb writer invites us to believe that “The tone of the collection ranges from the lyric—Trinidad as an island of great natural beauty—to an arresting grungy steaminess with dark comedy in between.” This beauty of landscape is obscured by the overwhelming degeneracy of the manscape. What the blurb describes as “an arresting grungy steaminess” is really an oppressive pervasive degeneracy of some elements and sectors of island life. Ramcharitar’s island people, as perceived by the protagonists of the stories, are either the degenerate descendants of the French Creoles, white and black, or debauched expatriate women, or ignorant Africans or backward-looking conservative Indians. he grotesques, whom earlier writers have portrayed with a satirical reductivity, have now been exposed sans humanité as irredeemable degenerates or lost devotees of an incomprehensible religion and lifestyle.

The blurb understates the truth when it advertises “a collection much concerned with the flesh—often in trangressive forms, as if the characters are driven to test their boundaries—and with the capacity of its characters to reinvent themselves in manifold, and sometimes outrageous disguises.” Far from this, transgressive sexuality seems the order of the day in certain circles, according to The Island Quintet, which presents figures, some recognizable to me under their deliberately transparent masks. In its own way The Island Quintet purports to retail some of the island’s recent political and social history, offering an account which culls details from the larger whole.

My major problem with the content of the collection is that the stories are smothered in the background. Too often a story stops as the author sketches in background information which is intended to explain characters, events and relationships in the story. Too often too the story is lost in the background and not developed as fully as it can be.

The first story “The Artist Dies” for example opens with the narrator’s staring out over the faces of the handful of individuals who attend the ceremonies marking the death of the Artist. Each of these individuals has a past—generally one of transgressive sexuality—and a relationship to the Artist—one in which excessive or transgressive sexuality plays some part. Ramcharitar sketches these pasts and relationships at some cost to the flow of the story. I am not sure if the final statement, “This life is nothing but a sport and a pastime; when we wake, we remember nothing,” is a commentary on the lifestyle of the Artist and his chosen playmates or the author’s commentary on life.

I am not sure of the conclusion to the story “The Blonde in the Garbo Dress” which features a confusion of mirrors. We are presented with a sense of pastness of the present and the presence of the past all blighted by the depravity—there is no better, indeed no other word of the white women past and present. I am not sure whether the simultaneous declarations of pregnancy by the two women signal parallelism or continuity.

“New York Story” presents the Colo family, Indo-Trinidadian peasants who, by trickery and luck, have relocated to New York where they perpetuate the wretched folkways of their past on the island. Patriarchy (including sodomy of a daughter-in-law), favoritism, ignorance and false sophistication are features of this lifestyle which it is implied is characteristic of some debased rural Hindus. The narrator, who in his own way, is as bad as the Colos, becomes the beneficiary of the generosity of a John Gotti type mafiosi whose life he saves. Safe now from the threat of deportation, the narrator imagines himself betraying his erstwhile hosts to the INS and exulting in their downfall, all save the much-abused Sarah and her child. Certainly the dark humour mentioned in the blurb is in evidence here, although the fiendish glee with which the narrator fantasizes the discomfiture of the Colos argues for something more sinister than dark humour.

“The Abduction of Sita” is a hopelessly bleak story. The presence of dual narrators and the interplay between them and other characters makes for an interesting narrative technique but the inorganic ending featuring Sunil’s sexual sadism and Maryse’s sexual masochism overwhelm the literary technique. It is almost as if the author is saying that there is only one way in which characters like these can end.

“Froude’s Arrow,” the last story, promises an arresting story centered on Froude, the mulatto who occupies a middle ground between white and black. In this story, however, the basic ethnic stereotyping and sexual transgressivity developed in other stories are present as the picturesque Asiatic comments detachedly on the supposed white and black liberals, the artistic community, the journalistic fraternity, the sex-starved female expatriates, the ignoramus painter Mokombo Cojo, the leading light in the Africanist movement and so on. While these are accepted as the core principles of the worldviews of the collection’s protagonists, whether in Porto Spana, London or New York, the story focuses on Froude who engages his dividedness  by engaging in a public polemic with himself by resurrecting to some extent the comments of James Anthony Froude and the response of JJ Thomas. Our Froude plays the role of the British historian and has his sister Jenny respond under the nom de plume JJ Thomas. This is an interesting way of presenting dividedness but the revelation that Froude is homosexual leaves me wondering if that socially unacceptable condition is ipso facto sufficient reason to discredit his perspective. Interestingly, Froude like the Artist of the first story thinks that the young Asiatic malehe possesses and perhaps transforms is also homosexual. I am not sure if this is merely an example of the “dark humour in between” as described in the blurb. by engaging in a public polemic with himself by resurrecting to some extent the comments of James Anthony Froude and the response of JJ Thomas. Our Froude plays the role of the British historian and has his sister Jenny respond under the nom de plume JJ Thomas. This is an interesting way of presenting dividedness but the revelation that Froude is homosexual leaves me wondering if that socially unacceptable condition is ipso facto sufficient reason to discredit his perspective. Interestingly, Froude like the Artist of the first story thinks that the young Asiatic malehe possesses and perhaps transforms is also homosexual. I am not sure if this is merely an example of the “dark humour in between” as described in the blurb.

As far as I can read, The Island Quintet offers only a few glimpses of the compassion advertised by the blurb. My own sympathies are with the parents of the Artist, with Sarah of “New York Story” and with Jenny, and with the parents of the protagonist in “Froude’s Arrow,” all essentially good people caught up in a corruption which leaves them bewildered. I suspect that they need their own stories to offset the trauma that is presented as normalcy on the island.

A brief review like this is inadequate for any judgement on the blurb declaration to the effect that, “In writing The Island Quintet Ramcharitar establishes himself as a truly significant Caribbean voice.”

|