|

|

|

|

December 2009

|

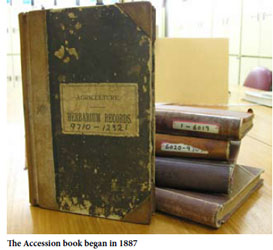

Housed at The UWI’s St Augustine Campus grounds since 1947 (even before the inception of The UWI), the Herbarium is, today, one of the University’s treasures. The Herbarium has its beginnings in the establishment of the Royal Botanic Gardens in 1818. Whoever held the post of Superintendent of the Royal Botanic Gardens collected specimens from the flora and put them into storage, but no one organized their collection so that it could be used. In 1887, John H. Hart became the fifth Superintendent and noticed his predecessors’ collections “tied up in brown paper parcels, put into out-houses, bed-rooms, closets, with no arrangement, or catalogue to guide anyone as to their contents. As a result 90% of the specimens were destroyed by insects.” Outraged, he proceeded to preserve, poison, mount and catalogue the salvaged specimens, some from as early as 1844, in an Accession Book, which continues to be used by the Herbarium today. The specimens were then stored in specially designed cabinets. This led to the formal establishment of the Herbarium in October 1887—122 years ago. Originally it was held at St. Clair, in the offices of the Department of Agriculture, where it provided botanical information to the nearby Royal Botanic Gardens, the Department of Agriculture and the Forestry Department. The Herbarium’s clientele expanded with the institution of the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture (ICTA) in 1924, when its collections were used by Professor of Botany, E.E. Cheesman, and his associates, W.G. Freeman and R.O. Williams of the Department of Agriculture, to compile a book, Flora of Trinidad and Tobago, published in 1928. In July 1947, to facilitate expanding botanical research and publication, the Herbarium was transferred to ICTA in St. Augustine. The collections were held in the Plant Pathology Department until 1953, when the Herbarium was moved to its own purpose-built room in the newly constructed Sir Frank Stockdale building, where it still resides to this day. In 1960, the University College of the West Indies took over the St. Augustine Campus and ICTA was incorporated as the Faculty of Agriculture. The task of managing and financing the Herbarium was allotted to the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, headed by Professor of Botany, J.W. Purseglove, until 1967. During that time Professor Purseglove assigned members of his staff the duty of collecting plant specimens and maintaining the Herbarium’s collection. His staff also aided in producing several volumes of the Flora of Trinidad and Tobago. Yet, the emergence of The UWI and the Faculty of Agriculture brought a change in focus, away from botany. Flora studies were discontinued and the value of the Herbarium declined. At that time, running the herbarium with no specific budget also proved to be an expense too hefty for the Department to continue. As a result, then Head of Department, F.W. Cope, proposed a financial takeover of the Herbarium by the government. In 1973, the Herbarium was declared a national asset and the collection was designated the “National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago” in an agreement with the Ministry of Planning and Development, where the Ministry would finance the National Herbarium indefinitely, while the University would administer the funds through the Bursary.

More than a century later, what began as a register for local flora has expanded to include other regional plants. The National Herbarium also provides botanical information to scholars. Since 1980, the Herbarium has hosted around 15,000 new visitors and has answered requests for information about plants, plant identification and field assistance. Its staff has identified over 20,000 plant specimens and added 20,000 new accessions to the same Accession book begun in 1887 by the Herbarium’s founder, John H. Hart. There are now over 70,000 specimens in the Herbarium’s collection. Over the past 28 years, the Herbarium has served The UWI directly, by becoming a major resource for four PhDs and six Master’s in Philosophy theses, with emphasis on Systematics, Ecology and Conservation of the flora in Trinidad and Tobago. The National Herbarium has worked with globally recognised institutions, including the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada, with which it undertook a study of the vegetation history of Lever Pond, Lake Antoine and Grand Etang in Grenada. It has also held workshops and training sessions on plant identification, funded by the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation in Agriculture (IICA), the Commonwealth Science Council (CSC) and the Organization of American States (OAS). The Herbarium also benefits from exchanging and loaning specimens to Universities and herbaria abroad for scholarly studies since these institutions, in turn, update specimen data and record it in any resulting publication. Thus, plant specimens from Trinidad and Tobago are spread all over the world, from Sweden and Germany, to The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in England and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. The Herbarium is then provided with a copy of the publication for its library. It also receives scholarly books in exchange for specimens. Selections from the Flora Neotropica series were obtained from the New York Botanical Gardens. Books and periodicals have also been donated to the National Herbarium from the Smithsonian Institution, the Fairchild Tropical Garden in Florida and Michigan University. Within the past five years, the National Herbarium’s facilities have undergone a major renovation and expansion and its number of staff has increased. It has also taken on the task of digitising its entire collection. To date, between 20,000 and 23,000 specimens have been digitised. In September 2005, the herbarium embarked on the Oxford/UWI Darwin Project with the University of Oxford in England. This project was funded £265,000 by the UK Darwin Initiative and endeavoured, according to a press release by the University of Oxford, to “create a detailed vegetation map of the islands and link the plant collections of Oxford and The UWI for the first time online.” The National Herbarium’s online plant database will also be linked to other collections around the world. A small team, led by Mrs. Baksh-Comeau and including Oxford professors Dr. Nick Brown, Ecologist, Dr. Stephen Harris, Taxonomist, and Dr. William Hawthorne, Conservation and Forest Ecologist, made its way to Tobago where it began a national inventory of the flora on both islands. This project, aiming to develop a Biodiversity Monitoring System for Trinidad and Tobago, proved to be “a very comprehensive and extensive survey,” Mrs. Baksh- Comeau said. Approximately 247 plots were explored and, though the team expected to uncover an estimated 10,000 new specimens, their search gave rise to 25,000 specimens between 2005 and 2008. The specimens were then taken to the herbarium, where 90 per cent of the species were identified, data-based and stored as voucher specimens.

In September of this year, an internship was established with the University of the Southern Caribbean and eight students set out on a three-month long journey with the National Herbarium. Their task was to mount 250 specimens each and within the first two months, each person had over 100 specimens mounted, with one person having already crossed the 250 benchmark. By the end of the internship, over 1600 specimens had been mounted. On that Friday, as the interns gave their final presentations at the Herbarium in front of a small audience including Head of the Department of Life Sciences and Agriculture, Professor John Agard it was clear how much they had gained. Mrs. Baksh-Comeau said that she particularly noticed the vast improvement in their technical skills, transformed from “all thumbs, to all manipulative fingers.” “As a pioneering exercise, (the internship) was a success,” she said. “It was very worth the adventure and risk that we took.” Now that some of its major endeavours have finished, new adventures beckon. A study on lichen biodiversity in Trinidad has already begun and Mrs. Baksh-Comeau has her own list of plans. She remains hopeful about moving the facilities into a new purpose-built building and would like to see it upgraded to the status of a regional herbarium, particularly to benefit the SIDS (small island developing states) in the Caribbean. Also on her list is the development of a virtual field herbarium, the expansion of the reference collection and, in the near future, DNA barcoding of specimens for quick identification.

(National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago website: http://sta.uwi.edu/herbarium/collect.asp) Herbarium |

One Friday at the end of November, seven students stood at the head of a conference room and gave presentations on their work, marking the conclusion of their three-month internship with the National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago. This was the Herbarium’s first attempt at hosting an internship and just one of its accomplishments this year.

One Friday at the end of November, seven students stood at the head of a conference room and gave presentations on their work, marking the conclusion of their three-month internship with the National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago. This was the Herbarium’s first attempt at hosting an internship and just one of its accomplishments this year. In 1976, Dr. Charles Dennis Adams joined The UWI Department of Botany and Plant Pathology as an ecologist and taxonomist. He successfully attempted to revive plant research in Trinidad and Tobago by employing a Graduate Curator for the Herbarium. In 1980 this post was approved by then Dean of the Faculty of Agriculture, Professor John Spence, and Yasmin S. Baksh was appointed to the post. This was the first and only time that the position has been filled as, 29 years later, the now Mrs. Yasmin S. Baksh-Comeau still holds her position as the Curator of the National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago.

In 1976, Dr. Charles Dennis Adams joined The UWI Department of Botany and Plant Pathology as an ecologist and taxonomist. He successfully attempted to revive plant research in Trinidad and Tobago by employing a Graduate Curator for the Herbarium. In 1980 this post was approved by then Dean of the Faculty of Agriculture, Professor John Spence, and Yasmin S. Baksh was appointed to the post. This was the first and only time that the position has been filled as, 29 years later, the now Mrs. Yasmin S. Baksh-Comeau still holds her position as the Curator of the National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago. Mrs. Baksh-Comeau said the Oxford/UWI Darwin Project opened up new areas for research, “particularly in the area of conservation of threatened and endangered species in our flora.” She hopes to collaborate further with the University of Oxford, “to extend the project to the small island states in the Caribbean,” she said.

Mrs. Baksh-Comeau said the Oxford/UWI Darwin Project opened up new areas for research, “particularly in the area of conservation of threatened and endangered species in our flora.” She hopes to collaborate further with the University of Oxford, “to extend the project to the small island states in the Caribbean,” she said.