|

February / March 2011

Issue Home >>

|

It starts innocuously with a bout of inactivity, overeating and some weight gain around the waist. As this happens repeatedly and your waist expands, it’s easy to alter your clothes or purchase a new wardrobe. But as your waist size grows, so do your blood pressure and the bad fats (cholesterol and triglycerides) in your blood, and before you know it you have the dreaded Metabolic Syndrome. As the name suggests, Metabolic Syndrome is a clustering of several of the most dangerous risk factors for heart attack and type 2 diabetes, and includes high fasting blood sugar (glucose), abdominal obesity, elevated cholesterol and triglycerides and high blood pressure. People with Metabolic Syndrome are twice as likely to die from, and three times as likely to have a heart attack or stroke compared with others. It starts innocuously with a bout of inactivity, overeating and some weight gain around the waist. As this happens repeatedly and your waist expands, it’s easy to alter your clothes or purchase a new wardrobe. But as your waist size grows, so do your blood pressure and the bad fats (cholesterol and triglycerides) in your blood, and before you know it you have the dreaded Metabolic Syndrome. As the name suggests, Metabolic Syndrome is a clustering of several of the most dangerous risk factors for heart attack and type 2 diabetes, and includes high fasting blood sugar (glucose), abdominal obesity, elevated cholesterol and triglycerides and high blood pressure. People with Metabolic Syndrome are twice as likely to die from, and three times as likely to have a heart attack or stroke compared with others.

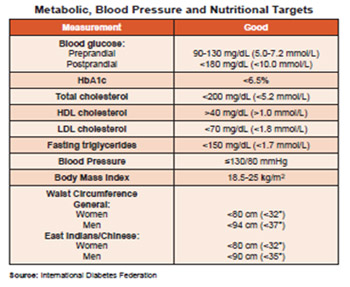

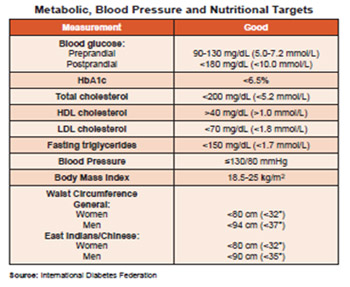

How do you know whether you have Metabolic Syndrome? The definition varies slightly from one region to another, but recently the International Diabetes Federation published widely accepted criteria now being used for defining the Metabolic Syndrome (Table 1). The major starting point for assessing whether someone has Metabolic Syndrome is an abnormally high waist circumference (WC) or a generous “inch pinch” around the waist. Traditionally, obesity is measured as Body Mass Index (BMI), which is a measure of someone’s weight in relation to their height. It is very important to know your BMI and to take the necessary steps to maintain a normal BMI because many studies have shown that as BMI increases so do blood pressure and risk for type 2 diabetes.

The definition of obesity in persons of different ethnicity can vary, and this is taken into account in Table 1. Indeed, persons of Asian ancestry (East Indians or South Asians and Chinese or Japanese) have increased risk for type 2 diabetes, heart disease and stroke at lower body weight and waist circumference than persons of African or Caucasian ancestry. There has been a similar argument for the relationship between cholesterol and risk The definition of obesity in persons of different ethnicity can vary, and this is taken into account in Table 1. Indeed, persons of Asian ancestry (East Indians or South Asians and Chinese or Japanese) have increased risk for type 2 diabetes, heart disease and stroke at lower body weight and waist circumference than persons of African or Caucasian ancestry. There has been a similar argument for the relationship between cholesterol and risk  for heart attack: East Indians seem to have a higher risk for heart attack at cholesterol levels which are considered normal in Caucasians. for heart attack: East Indians seem to have a higher risk for heart attack at cholesterol levels which are considered normal in Caucasians.

In the presence of an abnormally high waist circumference an individual must have a further two out of a possible four risk factors to be classified as having Metabolic Syndrome. These include abnormally high blood triglycerides, high blood pressure, high fasting blood glucose and low levels of HDL-cholesterol, which protects against heart attack. It is important to have regular measurements of these indices to assess Metabolic Syndrome risk. High triglyceride and low HDL-cholesterol are related to lack of exercise and overeating, although there may be a genetic cause, but this is rare. We tend to blame our genes for the increased prevalence of heart disease and diabetes, but although gene expression could partly account for this observation, the changes in gene expression are thought to be largely driven by dietary and lifestyle behaviours. Over the past few decades our gene pool has not changed, but there have been changes in some genes as a result of changes in dietary exposure.

Burden of Metabolic Syndrome and its components in Trinidad and Tobago

In 2007, my research team collaborated with the Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute (CFNI/PAHO) to conduct a national nutrition survey on a representative sample of the Trinidad and Tobago population. A total of 1254 persons aged 18-64 years were questioned and measured; we found that 26% had abnormally high WC (Men=18%; Females=39%). About 20% of the sample was obese (BMI>30kg/m2); approximately 45% of persons in this sample were overweight (BMI>25kg/m2). More recently, in a study conducted by my PhD candidate, Debbie Hilaire, on a representative sample of the UWI staff found that the prevalence of high WC was a whopping 36%, with about 20% regarded as being obese (See UWI Today January 2010 ).

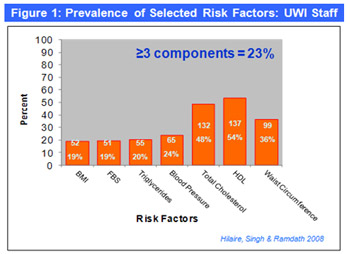

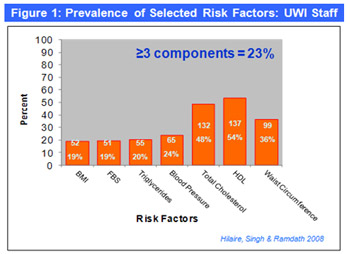

As shown in Figure 1, the prevalence of other Metabolic Syndrome risk factors was also high: high fasting blood sugar was present in 19% of the persons studied; 24% had high blood pressure; 20% had high triglycerides; 54% had low HDL-cholesterol and 48% had high total cholesterol. Taken together it is estimated that approximately 23% of this sample of Trinidadians could be regarded as having full-blown Metabolic Syndrome.

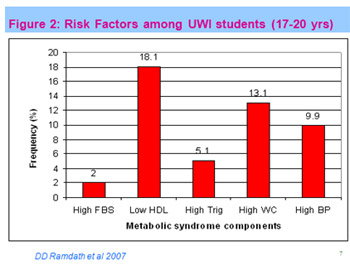

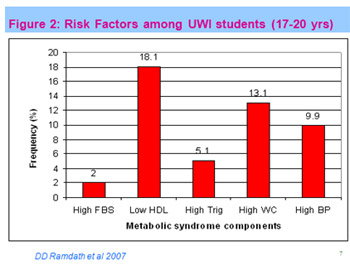

The study on UWI staff was preceded by another research project conducted by second-year medical students. At the start of the 2006 academic year at UWI, the young researchers surveyed 186 first-year entrants from Trinidad. In addition to measuring BMI and WC, blood levels of glucose, cholesterol and triglycerides were determined in order to assess the prevalence of risk factors for heart attack and diabetes among this group. Figure 2 shows that almost 10% had high blood pressure, 13% had large waist circumference and 18% had low HDL-cholesterol. These results show that risk factors for Metabolic Syndrome develop at an early age when it is possible to modify these with appropriate interventions (eg healthy eating and regular exercise). The study on UWI staff was preceded by another research project conducted by second-year medical students. At the start of the 2006 academic year at UWI, the young researchers surveyed 186 first-year entrants from Trinidad. In addition to measuring BMI and WC, blood levels of glucose, cholesterol and triglycerides were determined in order to assess the prevalence of risk factors for heart attack and diabetes among this group. Figure 2 shows that almost 10% had high blood pressure, 13% had large waist circumference and 18% had low HDL-cholesterol. These results show that risk factors for Metabolic Syndrome develop at an early age when it is possible to modify these with appropriate interventions (eg healthy eating and regular exercise).

No national data exist on the prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome or its risk factors such as cholesterol or high blood pressure. The Ministry of Health plans to execute the WHO STEPS study which will provide such information. However, in the absence of any other information, we feel confident that the observations made on persons at UWI provide a reasonably good approximation of the national picture. Many other researchers have reported a staggering increase in the prevalence of  obesity in Trinidad and Tobago. When we observe the heavy usage of the CDAP initiative, the waiting times for dialysis due to end-stage renal failure resulting from diabetic complications, the increasing number of young persons who have suffered a heart attack and the growing number of youths with type 2 diabetes, we must conclude that there is an undeniable problem with the growing burden of chronic diseases in Trinidad and Tobago. obesity in Trinidad and Tobago. When we observe the heavy usage of the CDAP initiative, the waiting times for dialysis due to end-stage renal failure resulting from diabetic complications, the increasing number of young persons who have suffered a heart attack and the growing number of youths with type 2 diabetes, we must conclude that there is an undeniable problem with the growing burden of chronic diseases in Trinidad and Tobago.

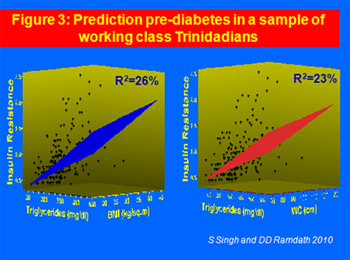

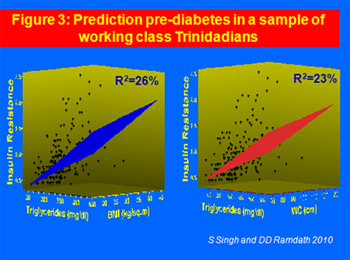

Protecting you and your family from Metabolic Syndrome

Using data from our various studies, another of my PhD students, Shamjeet Singh, has developed models to predict risk for developing type 2 diabetes by calculating the level of insulin resistance (pre-diabetes) and relating this to simple measurements of weight, height and waist circumference. In particular, Figure 3 shows that a combination of waist circumference and triglyceride or BMI and triglyceride can be used to predict whether someone has pre-diabetes. The predictive value is modest, at 23-26%, but this manipulation shows that by knowing someone’s BMI, waist circumference and triglyceride it is possible to assess their risk for developing diabetes.

Know your numbers Know your numbers

Clearly, knowing your numbers for the risk factors that comprise the Metabolic Syndrome is an imperative in reducing these risks among you and your family. Not only is it important to have these tests performed by a qualified health professional on a regular basis, knowing these numbers is equally or even more important. Following is a table that gives the desirable targets for the various risk factors for Metabolic Syndrome. This Target Table is taken from the International Diabetes Federation and forms part of a pocket guide for the management of diabetes in the Caribbean, which will be launched by the Caribbean Health Research Council shortly. These guidelines are prepared for health care professionals but it is useful for everyone to read these to understand the level of care they should expect and to become more involved in the management of their health. The full guidelines can be downloaded from http://www.chrc-caribbean.org/Guidelines.php. By knowing your numbers and relating these to the targets on this Table any individual can now assess their risk and increase their role in the self management of disease risk.

Does lifestyle change really work?

Obesity and weight gain are the starting point for Metabolic Syndrome, so it is important to engage in healthy eating (rather than dieting) and regular exercise. Healthy eating should not be confused with dieting. Dieting is a prescriptive process for persons who have an underlying disease that requires a specific diet. Dieting is sometimes used to initiate weight loss but cannot be sustained for a long period. Healthy eating should be the goal to maintaining a normal waist circumference and body mass index. Healthy eating is consuming a small amount of a variety from all food groups. Obesity and weight gain are the starting point for Metabolic Syndrome, so it is important to engage in healthy eating (rather than dieting) and regular exercise. Healthy eating should not be confused with dieting. Dieting is a prescriptive process for persons who have an underlying disease that requires a specific diet. Dieting is sometimes used to initiate weight loss but cannot be sustained for a long period. Healthy eating should be the goal to maintaining a normal waist circumference and body mass index. Healthy eating is consuming a small amount of a variety from all food groups.

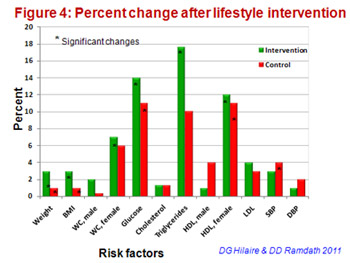

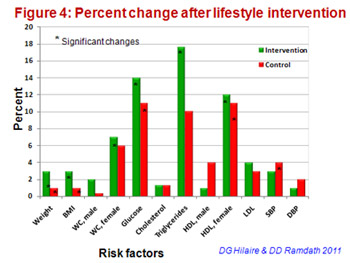

Given the high burden of disease risk and the 23% prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome among UWI staff, we collaborated with the Director, Human Resources and the Director, Health Services at UWI to conduct a six-month lifestyle intervention. Working with my PhD student, Debbie Hilaire (who is also a Registered Dietician), we designed and executed a controlled intervention: two groups of persons with two or more risk factors for Metabolic Syndrome were allocated into a group that received the usual information about healthy lifestyle, or another group that received individual diet counselling and fitness plan, monthly lifestyles workshop and regular health information. This intervention ran for six months when measurements were repeated and the results are shown in  Figure 4. There was significant weight loss and decreases in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol and blood pressure. This study showed that a healthy lifestyle that excludes overeating, fast foods and high fat foods, but includes regular physical activity and regular consumption of generous amounts of fruits and vegetables can result in a reduction of the factors that lead to Metabolic Syndrome. So again, it’s not the genes that we inherited that increase Metabolic Syndrome disease risk but rather, the lifestyles we adopt that influence the genes we possess. We need to therefore stop blaming genes and focus on eating the right greens to ensure that we always fit into our old jeans. Figure 4. There was significant weight loss and decreases in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol and blood pressure. This study showed that a healthy lifestyle that excludes overeating, fast foods and high fat foods, but includes regular physical activity and regular consumption of generous amounts of fruits and vegetables can result in a reduction of the factors that lead to Metabolic Syndrome. So again, it’s not the genes that we inherited that increase Metabolic Syndrome disease risk but rather, the lifestyles we adopt that influence the genes we possess. We need to therefore stop blaming genes and focus on eating the right greens to ensure that we always fit into our old jeans.

-Professor Dan Ramdath was former Head, Department of Preclinical Sciences, Faculty of Medical Sciences. UWI, St. Augustine. He is currently a Clinical Research Scientist with the Canadian Government where he leads a programme that involves human clinical trials to generate evidence for regulatory approval of health claims that impact on population health globally. Prof. Ramdath remains involved in several research activities at UWI; he supervises three postgraduate students and is a Scientific Secretary of the Caribbean Health Research Council.

|

It starts innocuously with a bout of inactivity, overeating and some weight gain around the waist. As this happens repeatedly and your waist expands, it’s easy to alter your clothes or purchase a new wardrobe. But as your waist size grows, so do your blood pressure and the bad fats (cholesterol and triglycerides) in your blood, and before you know it you have the dreaded Metabolic Syndrome. As the name suggests, Metabolic Syndrome is a clustering of several of the most dangerous risk factors for heart attack and type 2 diabetes, and includes high fasting blood sugar (glucose), abdominal obesity, elevated cholesterol and triglycerides and high blood pressure. People with Metabolic Syndrome are twice as likely to die from, and three times as likely to have a heart attack or stroke compared with others.

It starts innocuously with a bout of inactivity, overeating and some weight gain around the waist. As this happens repeatedly and your waist expands, it’s easy to alter your clothes or purchase a new wardrobe. But as your waist size grows, so do your blood pressure and the bad fats (cholesterol and triglycerides) in your blood, and before you know it you have the dreaded Metabolic Syndrome. As the name suggests, Metabolic Syndrome is a clustering of several of the most dangerous risk factors for heart attack and type 2 diabetes, and includes high fasting blood sugar (glucose), abdominal obesity, elevated cholesterol and triglycerides and high blood pressure. People with Metabolic Syndrome are twice as likely to die from, and three times as likely to have a heart attack or stroke compared with others.  The definition of obesity in persons of different ethnicity can vary, and this is taken into account in Table 1. Indeed, persons of Asian ancestry (East Indians or South Asians and Chinese or Japanese) have increased risk for type 2 diabetes, heart disease and stroke at lower body weight and waist circumference than persons of African or Caucasian ancestry. There has been a similar argument for the relationship between cholesterol and risk

The definition of obesity in persons of different ethnicity can vary, and this is taken into account in Table 1. Indeed, persons of Asian ancestry (East Indians or South Asians and Chinese or Japanese) have increased risk for type 2 diabetes, heart disease and stroke at lower body weight and waist circumference than persons of African or Caucasian ancestry. There has been a similar argument for the relationship between cholesterol and risk  for heart attack: East Indians seem to have a higher risk for heart attack at cholesterol levels which are considered normal in Caucasians.

for heart attack: East Indians seem to have a higher risk for heart attack at cholesterol levels which are considered normal in Caucasians.  The study on UWI staff was preceded by another research project conducted by second-year medical students. At the start of the 2006 academic year at UWI, the young researchers surveyed 186 first-year entrants from Trinidad. In addition to measuring BMI and WC, blood levels of glucose, cholesterol and triglycerides were determined in order to assess the prevalence of risk factors for heart attack and diabetes among this group. Figure 2 shows that almost 10% had high blood pressure, 13% had large waist circumference and 18% had low HDL-cholesterol. These results show that risk factors for Metabolic Syndrome develop at an early age when it is possible to modify these with appropriate interventions (eg healthy eating and regular exercise).

The study on UWI staff was preceded by another research project conducted by second-year medical students. At the start of the 2006 academic year at UWI, the young researchers surveyed 186 first-year entrants from Trinidad. In addition to measuring BMI and WC, blood levels of glucose, cholesterol and triglycerides were determined in order to assess the prevalence of risk factors for heart attack and diabetes among this group. Figure 2 shows that almost 10% had high blood pressure, 13% had large waist circumference and 18% had low HDL-cholesterol. These results show that risk factors for Metabolic Syndrome develop at an early age when it is possible to modify these with appropriate interventions (eg healthy eating and regular exercise). obesity in Trinidad and Tobago. When we observe the heavy usage of the CDAP initiative, the waiting times for dialysis due to end-stage renal failure resulting from diabetic complications, the increasing number of young persons who have suffered a heart attack and the growing number of youths with type 2 diabetes, we must conclude that there is an undeniable problem with the growing burden of chronic diseases in Trinidad and Tobago.

obesity in Trinidad and Tobago. When we observe the heavy usage of the CDAP initiative, the waiting times for dialysis due to end-stage renal failure resulting from diabetic complications, the increasing number of young persons who have suffered a heart attack and the growing number of youths with type 2 diabetes, we must conclude that there is an undeniable problem with the growing burden of chronic diseases in Trinidad and Tobago.  Know your numbers

Know your numbers Obesity and weight gain are the starting point for Metabolic Syndrome, so it is important to engage in healthy eating (rather than dieting) and regular exercise. Healthy eating should not be confused with dieting. Dieting is a prescriptive process for persons who have an underlying disease that requires a specific diet. Dieting is sometimes used to initiate weight loss but cannot be sustained for a long period. Healthy eating should be the goal to maintaining a normal waist circumference and body mass index. Healthy eating is consuming a small amount of a variety from all food groups.

Obesity and weight gain are the starting point for Metabolic Syndrome, so it is important to engage in healthy eating (rather than dieting) and regular exercise. Healthy eating should not be confused with dieting. Dieting is a prescriptive process for persons who have an underlying disease that requires a specific diet. Dieting is sometimes used to initiate weight loss but cannot be sustained for a long period. Healthy eating should be the goal to maintaining a normal waist circumference and body mass index. Healthy eating is consuming a small amount of a variety from all food groups.  Figure 4. There was significant weight loss and decreases in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol and blood pressure. This study showed that a healthy lifestyle that excludes overeating, fast foods and high fat foods, but includes regular physical activity and regular consumption of generous amounts of fruits and vegetables can result in a reduction of the factors that lead to Metabolic Syndrome. So again, it’s not the genes that we inherited that increase Metabolic Syndrome disease risk but rather, the lifestyles we adopt that influence the genes we possess. We need to therefore stop blaming genes and focus on eating the right greens to ensure that we always fit into our old jeans.

Figure 4. There was significant weight loss and decreases in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol and blood pressure. This study showed that a healthy lifestyle that excludes overeating, fast foods and high fat foods, but includes regular physical activity and regular consumption of generous amounts of fruits and vegetables can result in a reduction of the factors that lead to Metabolic Syndrome. So again, it’s not the genes that we inherited that increase Metabolic Syndrome disease risk but rather, the lifestyles we adopt that influence the genes we possess. We need to therefore stop blaming genes and focus on eating the right greens to ensure that we always fit into our old jeans.