The disturbing news that Trinidad and Tobago ranked among the highest in the world for the prevalence of diabetes was disturbed even further when Prof Surujpal Teelucksingh went on to reveal that children were now developing type 2 diabetes, the kind you associated with your grandparents when they said they had “sugar.”

The news didn’t get better, but it provided information that could reverse the trend – if people heed it. Unfortunately, it requires culture shifts that are so drastic that even when the first signs were spotted and reported 50 years ago by Dr Theo Poon-King, no significant headway has been made.

In January, Prof Teelucksingh presented the findings of a study done by PhD student, Yvonne Batson, which he and fellow researchers, Drs Brian Cockburn and Rohan Maharaj, have been supervising under the auspices of the Helen Bhagwansingh Diabetes Education Research and Prevention institute (DERPi). (See January issue of UWI Today http://sta.uwi.edu/uwitoday/default.asp)

The study not only identified this alarming trend for children, but Prof Teelucksingh dramatically pointed to the common factor of obesity in the group of diseases called the Metabolic Syndrome. He compared group photos of children from a half century ago and the children of our time were noticeably plumper. It was not cute.

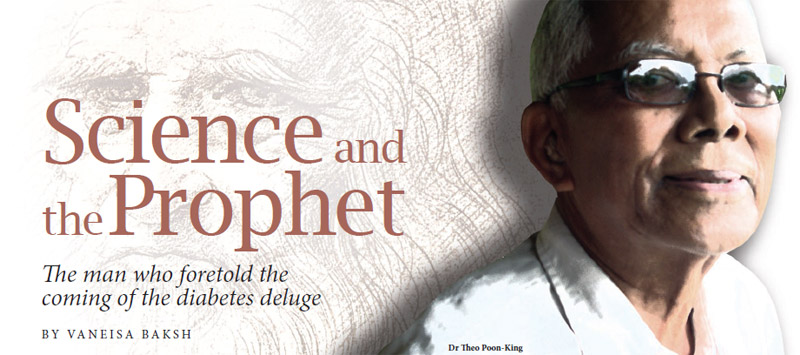

So when Prof Teelucksingh mentioned the work already done by Dr Poon-King, a man he reverentially refers to as the Da Vinci of medical research, it seemed natural to find out what had been done by this diabetes pioneer.

Dr Theodosius Ming Whi Poon-King epitomises the courtliness and grace of truly refined gentlemen of another era – he is 83 – and his mind is sharp, his recall clear, and his interests delightfully modern (He is currently reading “What the Internet is Doing to our Brains” by Nicholas Carr.).

He describes his passion for research as one inculcated at St Mary’s College when Fr Leonard Graf taught him how to study.

“Observe, analyse, synthesize,” said Fr Graf, before ushering him off to medical school in Ireland despite his scholarship award for Greek, French, Latin and Greek and Roman History. He had to start everything from scratch in that pre-med year in Dublin, but he won three gold medals by the time he graduated with first class honours and he believes it was through the techniques of research taught by Fr Graf, “the biggest influence on my life.”

It turns out that diabetes is just one of many areas in which he has made significant contributions and as I absorb the enormous girth of his work, I realise that Prof Teelucksingh is right to say that this man deserves an honorary doctorate from The UWI without delay.

Dr Poon-King’s work has ranged from the effect of scorpion stings on the heart, coronary heart disease, hypertriglyceridaema (elevated triglycerides), diabetes, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (a severe inflammatory kidney disease), acute rheumatic fever, streptococcal infections, immunology of streptococcal disease, and yellow fever… to paraquat poisoning.

He was the first to report on a link between scorpion stings and the heart. Scorpions were stinging like crazy in the sugarcane fields, and with his training in pathology he noticed something unusual in a 21-year-old canecutter from Barrackpore. He observed and analysed the next 36 scorpion victims and found that 70% had changes in their ECGs. Synthesizing the information, he made the important link.

In the seventies he started working with Dr Rasheed Rahaman and later, in the eighties with Dr Edward Addo (who died in 1999), on paraquat poisoning and treatments for it. According to research by Prof Gerard Hutchinson, between 1986 and 1990 paraquat poisoning accounted for 63% of suicides in T&T, and in south Trinidad from 1996 to 1997, for 76%; alarming figures. Dr Poon-King and Dr Addo were able to report a 72% survival rate from their treatment, which is now known internationally as the Addo-Poon-King regime.

He traced the source of Typhoid Fever in outbreaks of 1967 and 1969. He helped control Poliomyelitis in 1971, and in 1977 during a Yellow Fever outbreak, he worked with a team that demonstrated the virus on electron microscopy in human liver for the first time. Through him, four new nephritogenic streptococci were discovered locally and added to the international literature.

It is already a formidable range, and yet does not include work he has done in endocrinology. The work in diabetes, which set me on his trail, is the kind of work that makes you shake your head in amazement at the same time that you are trying to hang it for the shame of how we let things get out of hand.

At the invitation of Sir Harold Himsworth (the man who classified type 1 and 2 diabetes), he began a survey to find the prevalence of diabetes in Trinidad. That was fifty years ago. From July 1961 to July 1962, his team screened 23,900 people, finding 448 diabetics (1.89%) of whom 181 did not know they were.

In his report, he noted that, “Diabetes is more common in Trinidad than in North America or Great Britain,” but suggested that those figures were conservative. (The ranking is still high.)

The survey recorded race, sex, age, occupation, family history, obesity, diet, and parity of women (number of live births). Sir Harold had theorised that it was a diet high in fats that contributed to the large number of diabetics; but it was found that it was refined carbohydrates that were the real culprit.

“Roti is the root of all evil,” he says with a wry smile, stressing that white flour and white rice were the biggest contributors to type 2 diabetes. Identifying obesity and its root was a ground-breaking revelation then, but despite many public education initiatives, little has been done to dent the local desire for roti, bread, bakes, dumplings and all the other white flour treats.

“The problem is that people still think diabetes treatment is just about taking drugs,” he says. “It is about diet and exercise as well.” Writer Ian McDonald has said it succinctly: consume less, move more.

It comes full circle to the research now being done on the Metabolic Syndrome. Obesity is at the heart of it: the heart, the mind, the endocrine system, everywhere.

As he presented the findings on diabetes and children and warned of the increasing pressure on health care systems which will have to deal with spiralling depression, heart disease and diabetes, Prof Teelucksingh pleaded for government support for initiatives to provide testing in schools and public education campaigns. He reminded listeners of the deaths foretold by Dr Poon-King fifty years earlier if those same calls went unheeded.

Several researchers have answered the call to follow the insidious trail of diabetes. In many ways, the first path was cleared by Dr Theo Poon-King, and for his contribution to medical research, no honour should be spared.

|