|

|

|

|

February 2018

|

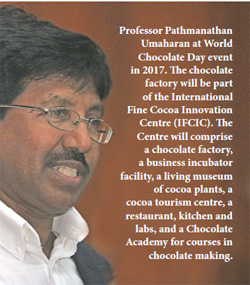

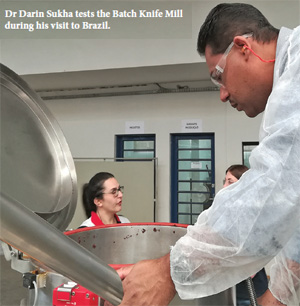

Fruity or floral, roasted or subtly spicy, the possibilities of chocolate flavours are endless. Some chocolates may have hints of jasmine or salty caramel, while others may seep into your tastebuds like dark velvet rum at midnight. But it takes skill, knowledge, imagination, and excellent cocoa beans to achieve true deliciousness. Flavour, like smell, is deeply linked to our emotions and memories. In cocoa beans, almost everything helps shape the flavour, starting from the genetic makeup of the cocoa plant, to the soil from which the plant draws nutrients, to the quality of the sunshine and the rainfall, “terroir” as the French call it. After you collect the beans, how you choose to ferment, dry, and process them to best bring out their body and richness is especially important for developing flavours. With a passion for cocoa and fine chocolate, Dr. Sukha leads the Food Technology Team at the Cocoa Research Centre (CRC) at UWI St. Augustine. He is very excited about the new chocolate factory in Mt Hope which is soon to be built. It has been his dream. At the time of this interview, he was in Brazil, testing new machinery for the chocolate factory. The factory will be part of the International Fine Cocoa Innovation Centre (IFCIC), a project being partly funded by a €2 million grant from the European Union/African, Caribbean and Pacific Science and Technology Fund. The IFCIC is the brainchild of plant genetics expert, Professor Pathmanathan Umaharan, who leads the Cocoa Research Centre tucked away in a wing of the Frank Stockdale building at The UWI. The IFCIC aims to rejuvenate our cocoa sector by helping to develop and spread better technologies, skills and quality products, as well as seed a lively, delicious, indigenous cocoa culture. IFCIC partners include the European Union, the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States, the ACP Science & Technology Programme, The UWI, and the Caribbean Fine Cocoa Forum.

Dr Sukha sits on a panel of judges for the International Cocoa Awards, of the Cocoa of Excellence Programme, a global competition celebrating the diversity of cocoa flavours, held every two years since 2009. There he gets to taste some of the world’s best-flavoured cocoa. The 2017 competition received 166 samples of fermented and dried cocoa beans from 40 countries: “Some of the flavours will blow your mind!” he said. Dr Sukha wants to help T&T cocoa producers develop their own equally wonderful flavours. Trinidad is uniquely positioned for this, because we grow Trinitario cocoa, one of the world’s finest. “While bulk cocoa beans, which are 95% of the market, might sell for about US $2,000/ton, fine flavour beans (5% of the cocoa market) sell for US$5,000-US$10,000/ton,” says a senior CRC staffer. There’s much money to be made from cocoa’s most popular product, chocolate. Chocolate is one of the best-loved foods on the planet, with global retail sales of US$101 billion in 2015. But so far, the lion’s share of cocoa profits is being made by a few big multinational chocolate manufacturers and retailers in the global north, such as Mars Inc (USA), Mondelez International (USA), Nestle SA (Switzerland), and Ferrero Group (Luxembourg/Italy). As T&T cannot compete with big bulk chocolate firms, it makes sense to focus on high-end, high-quality niche cocoa products. The IFCIC chocolate factory is one step towards this. It aims to boost local expertise in making excellent, unique home-made chocolate and other cocoa products. To accomplish this requires several things, including access to good and plentiful local cocoa stocks, training in manufacturing processes, access to a factory, and developing the craft and taste sensibility to discern, enjoy and make good chocolate flavours. Genetic research into the cocoa plant itself can help develop better tasting, resilient varieties. The Cocoa Research Centre has had a head start on such genetic research. It is home to the International Cocoa Genebank, the largest collection of cocoa varieties in the world, with 2,200 varieties. The CRC also has more than 80 years of research under its belt through its previous incarnations as the Cocoa Research Unit, and the Cocoa Research Scheme (formed in 1930 under the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture).

Prof Umaharan has long had a vision for the huge potential development of not only the T&T cocoa industry, but also the local anthurium and hot pepper sectors. But visions remain dreams until they are funded. So Prof Umaharan, six years ago, on behalf of the CRC, applied to the UWI’s RDI Fund to do a special project on the genetic control and identifying markers for some specific cocoa traits. The project, approved in 2012, looked at cocoa yield, pod characteristics, disease resistance, cadmium bioaccumulation, rooting characteristics and flavour. The project has since become a rising star among UWI’s RDI-funded projects because its findings attracted significant additional external funding to support more CRC work. For instance, it helped attract the EU/ACP €2.6 million funding to help build the International Fine Cocoa Innovation Centre, of which the chocolate factory is just one component. It also helped secure €500,000 in funding from ECA/CAOBISCO/FCC for a five-year project on mitigation of cadmium in cocoa, which is a growing health concern. And the MARS chocolate company is funding a joint cocoa genome sequencing project, where the CRC/UWI has partnered with Stanford University in the USA. Although funding has enabled the Centre to move ahead with its projects, those funds are fairly depleted, and there’s still a long way to go: Trinidad’s yields of dried cocoa beans, for example, are terrible: “In all T&T cocoa farms, the trees are aging. You get maybe 150 kg/hectare; compare that to 4,000 kg/hectare in some other countries,” comments Prof Umaharan. “Farmers here are still planting cocoa how they used to in the 1800s.” On many levels, the cocoa industry needs help. The chocolate factory is just the beginning. Cocoa in Trinidad: quick facts.(1 metric tonne =2,204.62 lbs)

MORE INFO

|

“Good chocolate is like a good piece of music,” says Dr. Darin Sukha: as you sample it, you’ll experience different flavour notes which combine to make a memorable harmony. It’s like an aria of taste, or meditating with your mouth: a quiet adventure in sensory pleasure.

“Good chocolate is like a good piece of music,” says Dr. Darin Sukha: as you sample it, you’ll experience different flavour notes which combine to make a memorable harmony. It’s like an aria of taste, or meditating with your mouth: a quiet adventure in sensory pleasure.  The IFCIC will comprise a chocolate factory, a business incubator facility, a living museum of cocoa plants, a cocoa tourism centre, a restaurant, kitchen and labs, and a Chocolate Academy for courses in chocolate making. The chocolate factory will produce cocoa nibs, cocoa liquor (the unsweetened liquid base for chocolate), and couverture or finished chocolate (both dark and milk). The idea is to have a total bean-to-bar model to stimulate the sector and enable applied research to have real community and industry impact.

The IFCIC will comprise a chocolate factory, a business incubator facility, a living museum of cocoa plants, a cocoa tourism centre, a restaurant, kitchen and labs, and a Chocolate Academy for courses in chocolate making. The chocolate factory will produce cocoa nibs, cocoa liquor (the unsweetened liquid base for chocolate), and couverture or finished chocolate (both dark and milk). The idea is to have a total bean-to-bar model to stimulate the sector and enable applied research to have real community and industry impact. In addition to its scientific research, the CRC also provides certification, post-harvest support, chocolate-making support, DNA fingerprinting, breeding support and disease screening, paid services for clients throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, earning some useful foreign exchange. And it has been running its own tiny in-house chocolate factory in UWI since 2012, making a 70% dark chocolate bar from local cocoa.

In addition to its scientific research, the CRC also provides certification, post-harvest support, chocolate-making support, DNA fingerprinting, breeding support and disease screening, paid services for clients throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, earning some useful foreign exchange. And it has been running its own tiny in-house chocolate factory in UWI since 2012, making a 70% dark chocolate bar from local cocoa.