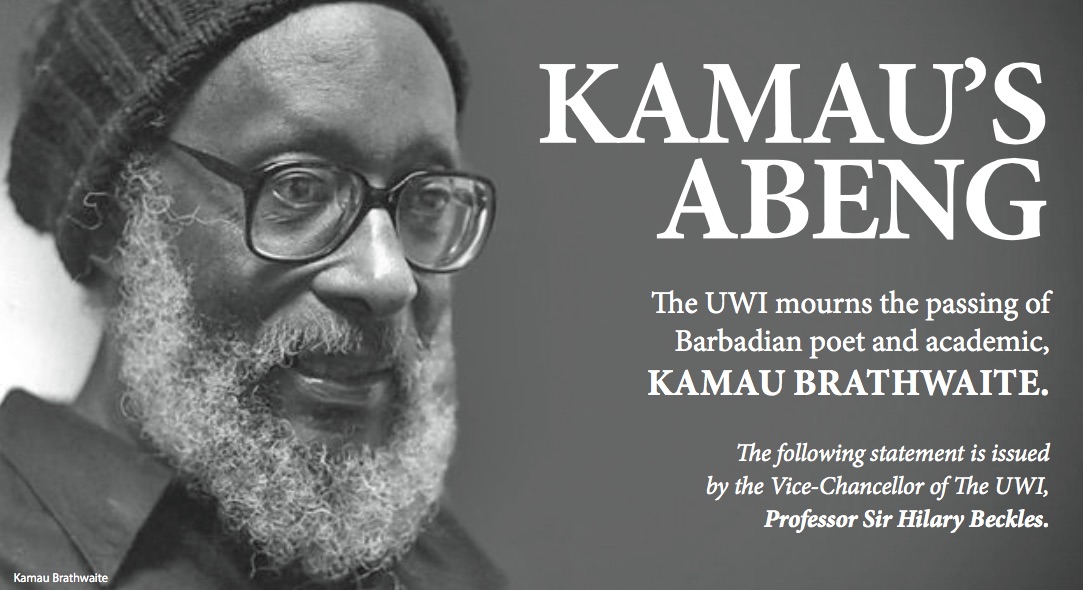

The University of the West Indies (The UWI) mourns the passing of Barbadian poet and academic, Kamau Brathwaite. The following statement is issued by the Vice-Chancellor of The UWI, Professor Sir Hilary Beckles.

We came to know and love Kamau Brathwaite as the keeper of the ‘abeng’, the African inspired use of the conch shell to spread manifesto messages among mountain maroons and their fellow forest freedom fighters.

The ‘abeng man’ grew a barberless beard, wore a roster of Rasta tams, sliding across our campuses, feet unchained in leathery slippers, and could never speak at a table without his thumb throbbing to the inner sound...the sound...the sound!

Our abeng blower took his task more seriously than many contemporaries were willing to admit. This was not Kamau’s thing; this was our war, our daily battles for justice, rights, and reasonableness.

When we worked together in the Department of History at The UWI Mona, he chose to live in a village on the edge of the Blue Mountains in eavesdropping reach of the maroons that still hold in sacred trust, life-giving terrain. He would come and go, the ‘mountain man’ with his abeng, but always writing, speaking, blowing, publishing, and calling!

Primordial poet of the middle passage, and philosopher of the ‘inner plantation’, our abeng man took the words of the empire, deformed their structure, mangled and decolonized their meaning in order to promote the rebellion against the inner estate where the real bondage of his people had persisted beyond the lawless Act of 1834 that ignored ‘Ewomancipation’ for ‘Emancipation’ when women were the majority on the plantations.

Regrounded in Ghana, where he discovered the abeng and began his journey as the craftsman of Afro-Caribbean words and the poetic verses they yield, our abeng man co-mingled a life of teaching, instruction, researching, writing and under-the-tree-reasoning, with a commitment to academia, love of The UWI that sometimes he thought ripped at his ribs, and concern for the poorest at the door.

Over the years, I watched him up-close as a batsman examines a brilliant bowler and marvelled at his ancestor-given gifts. He possessed a beautifully turbulent and unpredictable mind, honed in the watery underbelly of the middle passage, daily demanding new waves washing the beaches of our minds.

The abeng man was a soldier for our souls. For more than three scores and ten, his poetic passages told his tale. He cared for us—the used, abused and abandoned people/property of the empire. He called on us to be metamorphosed into missionaries, ontological armies marching to freedom from fear and distancing ourselves from doubt.

Born in Barbados, the centre/host of the slave-chattel enterprise, he journeyed to England—the holder of the intellectual property right to black chattel commodification—and then to Ghana, home of the soul, before middle-passaging to Jamaica, the land that had taken a firm stand. Along this slave route he took his liberation that gave us the sound of the free life he lived until, finally, he passed the abeng.

The UWI had heard and honed his sound, redefined its mandate and mission, and detached itself from the colonial scaffold. The Caribbean crier is now silent, though he will never be silenced; and so back across the middle passage he goes, for the final time to meet ancestors untold. They will blow the celestial abeng for him, and an African sun will shine upon their proud son.