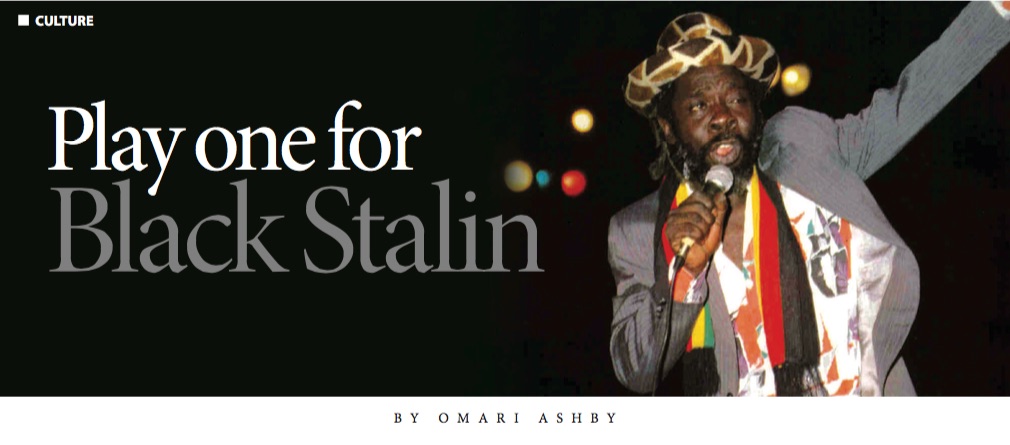

Some say that the limbo dance is the act of finding space where there is none. It should come as no surprise then that the Black Stalin started his creative career as a limbo dancer, because Leroy Calliste found space where there was none. Space as a calypsonian, as a voice for the common man, a voice for Caribbean unity, and a voice against oppression.

His calypso journey started in 1959 at the Good Shepherd Hall in St Madeleine and in three short years he would find himself singing in the Southern Brigade calypso tent. From there, he would go on to conquer stages nationally and then globally, picking up five Calypso Monarch titles along the way. But Stalin’s impact goes way beyond his titles. Indeed, his music and his message made him the quintessential Caribbean man.

With his first full length album, To De Caribbean Man in 1979, Stalin revealed himself to be a gifted lyricist who could craft songs dealing with the issues of the day from the people’s perspective. Songs such as De Same Ole Thing, Play One and Caribbean Unity showed that his early success was no fluke, but more significantly, it showed us a man who in his compositions would not lean on clichés or be satisfied with mere observations. No, Stalin would proffer solutions and action plans. In Caribbean Unity, he critically examined the failure of Caribbean leaders to unite the region and recognised the importance of acknowledging our common socio-historical context.

“You say dat de federation

Was imported quite from England

And you going and form ah Carifta

With ah true West Indian flavour

But when Carifta started running

Morning, noon and night all ah hearing

Is just money speech dem prime minister giving

Well I say no set ah money, could form ah unity

First of all your people need their identity”

Caribbean Unity stoked controversy when it came out, and it still sparks debate in contemporary discussions of race, gender, and Caribbean integration. This is an indication of Stalin’s ability to create songs that are both topical and timeless.

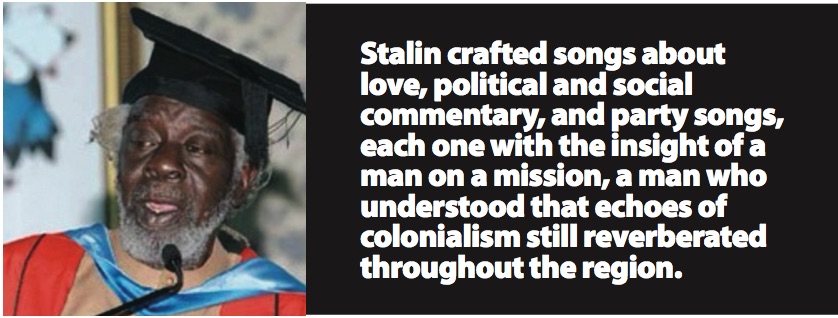

Stalin crafted songs about love, political and social commentary, and party songs, each one with the insight of a man on a mission, a man who understood that echoes of colonialism still reverberated throughout the region. In Bun Dem he would plead his case to be given the job to “deal” with the oppressors of his people.

“Judgment morning, ah by the gate and ah waiting

Because ah begging di Master, gimme ah wuk with Peter

It have some sinners coming, with them I go be dealing

Because the things that they do we, ah want to fix them personally.

Peter wait, Peter wait, Peter, look Cecil Rhodes by the gate.

Bun he! Bun he!

Peter, look the English man who send Cecil Rhodes to Africa land.

Bun he! Bun he!

Peter, take Drake, take Raleigh, but leave Victoria for me.

Bun she! Bun she!

Peter, ah doh care what you say, but Mussolini, he cyar get away.

Bun he! Bun he!”

The opening refrain of “Jah Know!” gave an indication that this “bunning” was righteous and overdue, giving voice to a sentiment permeating the Caribbean space at the time.

Nation Language, as Kamau Braithwaite calls it, was as important to Stalin’s fight against oppression as his biting lyrical salvos.

“We normal way of speaking, Africans always resisting de European language. Ah mean we get licks tuh learn English. So we speech is resistance language.”

The above quote from Stalin was taken from an interview given to Winthrop R. Holder in 2001. Stalin was making the point that resistance language is the key to calypso. He argued the “whole world have to see us through our language”. I would argue that through the Black Stalin’s music, the whole world did. He understood what it would take to dismantle the colonial project. He knew it was as much about what he said as how he said it. Stalin was a warrior of the word in every sense.

Former UWI lecturer the late Dr Louis Regis wrote two books on the Black Stalin, 1987's Black Stalin – The Caribbean Man, and 2007's Black Stalin Kaisonian. The latter publication traced Stalin’s development from apprenticeship at the South tent, his entry into Port-of-Spain, his work with Sparrow in the Original Young Brigade Tent, his mentorship under Kitchener, and to his own emergence as mentor and inspiration to a new generation of Calypsonians.

On Friday, October 31, 2008, Black Stalin was conferred the Doctor of Letters (DLitt) by UWI St Augustine’s Faculty of Humanities and Education. He often mentioned in his interviews the many theses written on him and his calypsos. So, it was indeed fitting that the Caribbean man was honoured by one of the institutions that stands as evidence of what can be achieved through regional co-operation.

“He was acutely conscious of our shared history, culture, passions, and concerns, and expressed them in his songs in a way we never could ourselves. In the true tradition of calypso, Stalin was also a griot, chronicling the issues and philosophies impacting our daily lives.”

This was part of a statement given by Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley on his passing. Dominica’s Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit said of Stalin, “While Leroy Calliste was a national of Trinidad and Tobago, he was also a Caribbean man and always stood and supported the Black race. He was an oral historian of our regional society as well as politics, whose amazingly crafted lyrics and melodies will abide as a testament to the life and culture, along with the times of our region and its people.”

These sentiments were echoed throughout the region about Leroy Calliste (DLitt), the limbo dancer from San Fernando, the Caribbean man, the Black Stalin.