|

January 2010

Issue Home >>

|

By Ira Mathur

I mumbled something about working in the Government Information Division, feeling horribly pedestrian, and he responded quicker than light with a question: Well then, can you multiply 25435 by 234? Then laughed raucously as I looked up, completely floored (I’m refiguring the numbers, but you get my drift). He vanished into the Savannah. But I saw him again, directing his play (may have been Moon over Monkey Mountain) at the Old Fire Station building which then housed the Trinidad Theatre Workshop he’d started in 1959, jocular, intimate with his actors, clearly relishing the authenticity of producing one of his plays, here, by people he loved.

A few years later came “The Bounty,” a slim volume of poetry which, while retaining his unstinting examination of our new world—the unlikely conversion of strands of four continents, a colonized people with lost languages and clean slates, who resist further colonization and maintain authenticity. It is a celebratory volume: lush and tender, with intimations of loss and a claim too of other continents. (Remember this? I’m just a red nigger who love the sea/ I had a sound colonial education/ I have Dutch, nigger, and English in me/ and either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.)

By then he had already produced as if a mere tossing of omelettes (a phrase borrowed by Virginia Woolf) not simply (ha!) “Omeros,” but the bulk of his twenty plays, enough landscape paintings to fill an exhibition, essays, and a Nobel lecture that has already in his lifetime become a timeless classic: the Ramleela, acted out in Felicity, plucked out of obscurity.

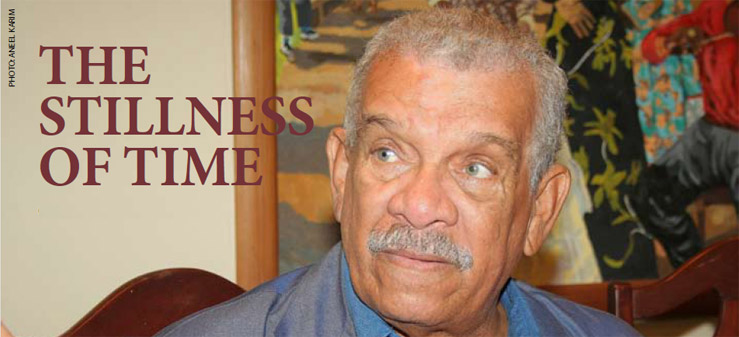

This January, when The University of the West Indies had a week-long poetic and literary tribute to this Nobel Laureate, the poet was far more subdued. There were intimations of the man I’d met years back in the chuckles in his own wit in our unique humour, his obvious enjoyment at watching the audience howl with laughter during the performance of Fragments.

But he was different, older. His twin brother was dead. His sister’s death was fresh in his memory. The diabetes was obviously taking hold of his body. And so when he read from his latest volume of poetry, “White Egrets” to be published in April this year, it was heartbreakingly lovely. His preoccupation of time, with the here and now, with memory and rain, is reminiscent of TS Eliot. His subject, as he put it before he began to read, a kind of quiet, meandering through St Lucia, London, New York, Trinidad, Italy—his preoccupation with the light making transitions between continents seamless. He maintains in “White Egrets” that the perpetual ideal is astonishment. He strives for it, but also falls into stillness, a quiet, that could be death, that could transcend it.

Consider the Sweet Life Cafe from “White Egrets”:

If I fall into a grizzle stillness

sometimes, over the read-chequered tablecloth

outdoors of the Sweet Life Cafe, when the noise

Of Sunday traffic in the Village is soft as a moth

working in storage, it is because of age

which I rarely admit to, or, honestly, even think of.

I have kept the same furies, though my domestic rage

is illogical, diabetic, with no lessening of love

though my hand trembles wildly, but not over this page.

My lust is in great health, but, if it happens

that all my towers shrivel to dribbling sand,

joy will still bend the cane-reeds with my pen’s

elation on the road to Vieuxfort with fever-grass

white in the sun, and, as for the sea breaking

in the gap at Praslin, they add up to the grace

I have known and which death will be taking

from my hand on this chequered tablecloth in this good place.

In the interview I had with him his one regret (and there were many: he wished he’d written more, done more) was that he hadn’t been tender enough towards our islands). Walcott bemoaned our self loathing. The sum of what we are, he felt, the amalgam of many continents, allowed us a sophistication and identity that went far beyond that claimed by people of the old world, be it Italian or Persian. We had three continents, four, for God’s sake. They had the one. He wanted less veneration of that old world and a greater recognition of our own authenticity.

At 80, Walcott should have no regrets. If what we feel now is a lasting gratitude for helping to restore our lost selves, for taking us out of the reach of imposed touristy stereotypes, allowing ourselves confidence in who we are, we should let him know. All his work, all his greatness, can be distilled to one point, that of a paean to our New World, that of love, of a boundless, heartbreaking tenderness for us, for the continents we inhabit in these tiny islands.

|