|

|

|

|

January 2010

|

My community is the world

…I begin by taking as generally recognized (whatever one’s own response to it may be), Walcott’s ideal of multi-culturalism and hybridity, the idea of “the interlocking of the races,” of the Port of Spain of his desire as “a city ideal in its commercial and human proportions” which would be “so racially various that the cultures of the world—the Asiatic, the Mediterranean, the European, the African—would be represented in it [and] its citizens would intermarry as they chose, from instinct, not tradition, until their children find it increasingly futile to trace their genealogy.” I have thought it remarkable that from early Walcott sought to imagine himself into Indo-Caribbean mind-space, especially when we consider that the (East) Indian presence in St Lucia was very much a minority. I once heard the late Earl Warner say something about the play The Sea at Dauphin (1954) which he was directing at the time, and what he said articulated something I had felt but unconsciously. That play is dominated by the eloquently God-cursing, history-cursing Afa, but Warner said that it really became Hounakin’s play, the tragedy of the old Indian Hounakin, who is the test of Afa’s humanity. Walcott’s compassion and respect for the Caribbean person of the Indian diaspora was developed in another play, Franklin, which has, regrettably to me, never been published. In his portrayal of Ramsingh and his daughter Maria, Walcott builds on his depiction of Hounakin. Ramsingh, too, is a tragic figure, unable to come to terms with the erosion of his cultural traditions. Then there is the poem “The Saddhu of Couva,” and the use, in the Nobel lecture, of the performance of the Ramleela at Felicity as the foundation-stone, so to speak. When we come to Africa, we are in uneasy terrain. Walcott has not been known for any desire to “inhabit” Africa. Harold McDermott has remarked his “seeming failure to accord the African the same privilege he does to the European in his work…”. Decades earlier, Maria Mootry, comparing the poetry of Brathwaite, Césaire and Walcott wrote: “As a man committed to ‘West Indianness,’ Derek Walcott tends to play down African influences and to insist on the West Indian’s potential for creating a new world.” That was true enough, but later in the same piece she spoke of Walcott’s “rejection of Africa.” True enough, in his early poetry, such instances of African consciousness in the Caribbean as he essayed tended to be of the more questionable kind, as in “Chapter V” and “Chapter VI” of “Tales of the Islands,” and in the story of Manoir, the island’s “first black merchant baron” (Another Life), “pillar of the Church,” and his pact with the Devil in Another Life. The much-cited “A Far Cry from Africa,” while stating some allegiance to Africa, has its problems and has come in for some strong criticism. Walcott also emphasized the transported African’s loss of memory of Africa—“customs and gods that are not born again” (“Laventille”), seeking to turn this “deep, amnesiac blow” to the advantage of his thought-provoking theory that this erasure of memory enabled Caribbean people to free themselves of the tyranny of history and to inscribe their presence on a “virginal, unpainted world” (Another Life) and to create a world like nothing the world had ever seen. It is worth remembering that Walcott’s position was, at the time, partly a reaction against the upsurge of Black African consciousness in the Anglophone Caribbean in the later 1960s and early 1970s, which he saw as being too much of “political nostalgia” for “a kind of Eden-like grandeur.” Hence the necessity of Makak’s dream journey back to Africa to purge himself of his illusions, just as he had to kill, psychologically speaking, the ghost of the White Goddess who had held him in thrall. At the same time, though, and interestingly, although he acknowledged that he didn’t “think in the African mode,” “that is not to say one doesn’t know who one is: our music, our speech—all the things that are organic in the way we live—are African.” Again, “The African experience is historically remote, but spiritually ineradicable. Nothing has really been lost,” and, he comes to say in the Nobel lecture, “even the actions of surf on sand cannot erase the African memory…”. More to the point, though, is that Africa and reconnection with Africa eventually came to be represented in a major, regenerative, self-realizing way in Walcott’s poetry, notably in Omeros. If I may be permitted to quote myself: “If the poem brings to a head Walcott’s long involvement with the classics, it is also his deepest, most unqualified acknowledgement to date of the African presence in the Caribbean.” Two crucial sequences are those in which Achille makes his dream-journey to Africa and Ma Kilman journeys into the forest to find the lost African root that will heal Philoctete’s wound, symbol of all the wounds of heart and history that the poem probes. Achille’s journey parallels but contrasts with, balances Makak’s. It is a journey to complete himself, not, as with Makak, to discard a misguided part of himself. Similarly, Ma Kilman’s journey into the forest revises the ironic “truth” enacted by the story of Manoir: that “One step beyond the city was the bush. / One step behind the churchdoor stood the devil” (Another Life). Drawn by her subconscious African memory, she leaves her pew in church to go into the forest to find the healing herb.

“I don’t want to summarise it in a sentence because there’s bound to be a germ from the experience that I might use for writing. The one thing I would say is that it felt as if the years between Africa and the Caribbean, the 300 or 500 years, had vanished. A weird feeling.” Perhaps there will be more to come on the matter of Walcott’s inhabiting, or being inhabited by Africa. But to return to The Prodigal. He returns to his island in pre-Easter drought, and notes that the ground dove, which “flew / up from his path to settle in the sun-browned / branches that were now barely twigs”, coos with a “relentless … tiring sound” that is “not like … the flutes of Venus in frescoes”. In his “scorched, barren acre”, “he had the memory of rain / carried in his head, the rain on Pescara’s beach”. The drought breaks, and the rain images the blessing and renewal of the return home, but it is now, as the poem draws to its close, even in the peace and fulfillment of “the enclosing harmony that we call home”, that the dialogue between the Caribbean and Europe comes to a head in complex twists and turns, nuanced, subtilized, to a new level of self-conscious scrutiny of how “we have tortured ourselves / with our conflicts of origins”. The simultaneous inhabiting of disparate places is true, but conflicted. The persona reaches the point where he asks himself, “So has it come to this, to have to choose?” To choose, that is to say, between the island and Italy, between Canaries and Venice, between “the marble miracles of the Villa Borghese” and “villages of absolutely no importance”, with “streets untainted / by any history”; between “a plank bridge” and Florence’s fabled Ponte Vecchio. But, no, he says, “the point is not comparison or mimicry.” “Both worlds are welded, they were seamed by delight.” So the blending is enacted when A crowd crosses a bridge To inhabit, simultaneously, different, shifting, overlapping spaces is, to borrow a phrase from Tiepolo’s Hound, to live by “maps made in the heart”, such maps being truer than the maps of everyday, factual use. While, in his right ear sounds “oak-echo, beech-echo, linden-echo” (62), his left hand writes “palms and wild fern .. / sea-almond … and agave,” but the one set is “not [the] opposite or [the] enemy”of the other. So, the stately Caribbean cabbage palm, the palmiste, stands beside “Doric and Corinthian” columns in the same line of verse, on equal terms. The palmistes speak, in their “correcting imprecations,” saying to poet and reader, In other words, they were and are only themselves, and that is everything. In the final analysis, there is no resolution in the sense of accepting one place and rejecting the other. Europe will still have its place in the poet-Prodigal’s head space, but he knows where his groundings are, he knows where is home. It is where he has the privilege of “mak[ing] each place” new again from naming it, the gaping view Incidentally, the representation of home provides another instance of the simultaneous inhabiting of different places. Home is configured, in the most particular sense, as one would expect, in images of St Lucia, but at times it is also configured in images of Trinidad, “Sancta Trinidad” as he says, and more particularly the Santa Cruz valley, locale of the white egrets that will provide the title of his next collection of poems: Santa Cruz, in spring. Deep hills with blue clefts. Significantly enough, the poem ends imagining another kind, another level of space, beyond worldly spaces, another “idea of home,” another idea of “Out There.” At the end, the poet-Prodigal is on a dolphin-sighting boat ride, heading out between Martinique and St Vincent. In a visionary, epiphanic close, the dolphins become the possibility of angels, We may simultaneously inhabit worldly and other-worldly spaces. Now, after all that, listen to this. In its list of “The Best Books of 2007,” Contemporary Poetry Review named, as “Best New and Selected Edition,” Derek Walcott’s Selected Poems. On the winner in each category, there was a comment. Here is the comment on Walcott: “Yes, he won the Nobel Prize, but does Derek Walcott really get the respect he deserves from his fellow poets? His American colleagues tend to ignore him, while the Brits don’t claim him as one of their own. ‘What are his politics? Who does he belong to? What group does his work represent?’ You can just imagine the academics asking their reductive questions about him and shaking their heads in dismissal. Walcott is, however, one of the greatest poets alive in English—only Richard Wilbur, Seamus Heaney, and Geoffrey Hill are in his league.” In other words, “Where does he belong, especially since acceptance and acclamation depend on our being able to place him, never mind that he has said, ‘My community, that of any twentieth-century artist, is the world’ (Conversations, 83)?” Interestingly enough, he has also said, “I think it’s very exciting to be outside English literature, English literature in a hierarchic sense” (Conversations, 47). And speaking of himself and his close Nobel laureate friends Brodsky and Heaney, he remarked, with an implicitly self-confident sense of place, “The three of us are outside of the American experience” (Conversations, 119). Haven’t “the academics asking their reductive questions” ever heard of the Caribbean? What can we say: “Alas, poor Derek?” Or, better, following the CPR line, “More power to Walcott”? Perhaps I should say, “So much for all my wanderings and wonderings about the desire to inhabit different places simultaneously.” |

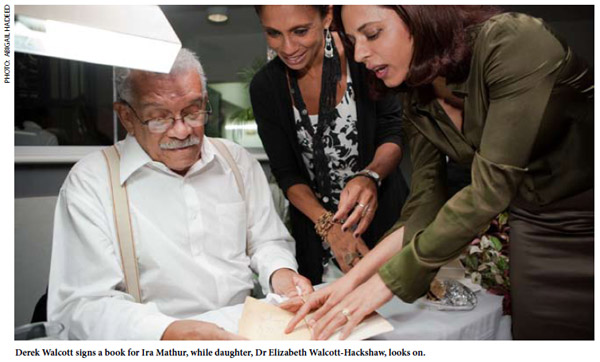

Professor Emeritus Edward Baugh delivered the keynote address at the opening ceremony of the conference in celebration of Derek Walcott, Interlocking Basins of a Globe, held at The UWI, St Augustine from January 13-15, 2010. This is an excerpt from Prof Baugh’s address which was titled Walcott’s Island(s), Walcott’s World(s): On inhabiting disparate, shifting, overlapping spaces.

Professor Emeritus Edward Baugh delivered the keynote address at the opening ceremony of the conference in celebration of Derek Walcott, Interlocking Basins of a Globe, held at The UWI, St Augustine from January 13-15, 2010. This is an excerpt from Prof Baugh’s address which was titled Walcott’s Island(s), Walcott’s World(s): On inhabiting disparate, shifting, overlapping spaces. In a recent interview, Walcott, telling the interviewer that he is “travelling [now] more than [he] ever did before”, and that “seeing another place is always good,” let on that he had recently been to Nigeria, “quite an experience,” and that that was his first time in Africa. The interviewer, Dante Micheaux, then asked him what the experience of Nigeria was like. This was his reply:

In a recent interview, Walcott, telling the interviewer that he is “travelling [now] more than [he] ever did before”, and that “seeing another place is always good,” let on that he had recently been to Nigeria, “quite an experience,” and that that was his first time in Africa. The interviewer, Dante Micheaux, then asked him what the experience of Nigeria was like. This was his reply: