|

|

|

|

June 2009

|

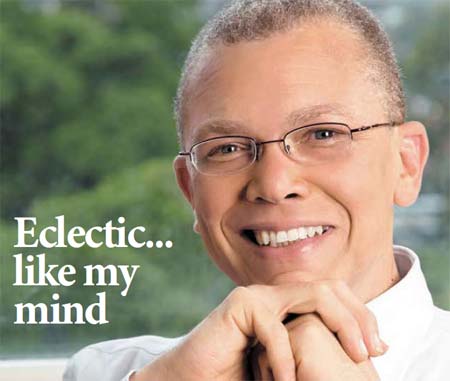

At 51, Robert Bernard Riley has been Chairman and CEO of bpTT (formerly Amoco) for nearly a decade and is one of the most powerful men in the region, but his early life was a struggle that endowed him with a moral compass that directs his way of life and his company’s corporate culture. He was born on September 2, 1957 to Rupert and Camilla and grew up on the Southern Main Road in Curepe with his two younger sisters and other relatives nearby. They were a poor family, held together by faith and the discipline doubtless instilled from his father’s Barbadian ancestry. “I would say my parents lived their whole life on faith because there was not much else to live on,” says Riley as he outlines the pallor of their poverty. “It was right on the edge of marginal. We had some tough days. I wouldn’t say I was abject poor. I always had a roof over my head. I always had some thing to eat. But there were difficulties. There were difficulties obtaining the schoolbooks, the schoolbags…” he trails off then regains momentum as memory broadens. “But they were really, really great parents. They were disciplined, they taught us about right and wrong. They taught us about life. My mother, I would say, is the real key why I think I have such a huge appetite for learning and reading.” He attended the traditional Curepe Hindu Vedic School “just around the corner,” and his immersion in Christianity didn’t interfere. “I had no sense of racial or religious boundaries,” he says, and he does not like stereotypes. “Generalisation is a really poor way to describe the colour, the breadth of people,” he says. “I was going to this Hindu Vedic school, praying my prayers on a morning, dancing Indian dances. Those schools had treats on a Friday, they were civilised.” Surrounded by farms belonging to the University and the Government, with milk and fruit smells wafting across from Ramcharan’s opposite and a soundtrack of hammers and saws coming from Peter’s wood-working (one imagines varnish scents too), Riley says people laugh when he tells them he grew up in the bush. “It felt country then.” His mother took him out of the country by encouraging him to read and his father supported the habit with occasional forays into Woolworth’s to get Louis L’Amour westerns on sale. The love for reading and learning was his greatest childhood legacy, infusing a sense of possibility that has enabled him to see opportunities through chinks. “I didn’t have to be limited by where I was or where my physical experience was. I could go and look into someone else’s expression of it and learn, and to this day, I approach everything with a certain methodology. I learned very early that I didn’t have to experience it all in order to know it, and that I could go beyond the paradigms of my experience. I like the challenge of learning and mastering. I’m always doing that.” He still reads, lamenting that “a lot of people who are busy in life are no longer reading. They do a little Internet stuff, but I still read. I still see books and reading as leisure and exposure.” The voracious reader, whose parents were “soughtafter singers” in church activities, became the devoted musician: first piano and then the guitar. “Music was a very, very important part of the sanity of my teens in particular, and the frustrations of the challenge of the constraints of the church,” he says. He’d inherited his father’s baritone and sensitive ear, and music became his abiding haven and joy. If he could live again, he says, he’d be a musician. “Today for me still the great relaxation and method of thought is to pick up a guitar and just play. Something goes on,” he says. “I believe when you distract the mind, you solve problems. So the more the pressure, the more I play.” Trinity College was an accommodating environment for the teenager struggling with “radical charismatic church” demands and the other secular “attractions.” Under principal Courtney Nicholls there were “wide boundaries” that you crossed possibly only with “sinister intent” and then you got into a lot of trouble. “But it was almost understood that boys got into trouble. I remember everything from when we made gunpowder and cracked the sinks all the way up to the funny things we did with sodium and water to blow our buttons off. In a sense there was a leeway, an understanding; we got caned a lot but there was almost like a private understanding in school that you’d really have to get into the realm of, I guess, truly sinister intent to get beyond.” Riley has two Bachelor’s degrees from The UWI. The first, in Agricultural Science, came about mainly because it was the only area where he could get financial assistance, and the other, in Law, came about while he was working at the Ministry of Agriculture and getting involved in land distribution projects involving lawyers. He suddenly realised Law was what he wanted to do, and he took off for Barbados, leaving his new bride, Patrice, to adjust to a couple years of long-distance love. He reflects that his first degree was so broad in its offerings that it suited his eclectic tastes perfectly and gave him the platform on which to ground his philosophies in practical applications. Sociology, physics, chemistry, geology, work on land distribution, economics, and understanding rural communities, environmental issues, and systems-thinking, shaped the policies of his influential corporate world. It was “eclectic, like my mind,” he says, and he believes the diverse experiences serendipitously combined to enable him to be a strong and sensitive leader. “Good turns do come back,” he says, aligning his phenomenal life journey with a karmic chain of people and opportunities. “I have experienced it in my life over and over and over. People are so generous to me.” The Riley Credo I really love people. Some people are motivated by money, some people are motivated by fame; I think I am motivated by bringing the best out of people. Every conversation with a person should leave them more motivated and better off. Not because I have given them some great insight but because the conversation has inspired them, caused them to try to do something better and different than before. Every conversation is also an opportunity to pick something up that might help you to do what you’re doing better. I guess I always have time to listen. I really do believe that there is no rank. I absolutely detest the idea of the total leader. I think it is passé and old and I think it is destroying the Caribbean. I think the modern leader is one who really has a vision, has something burning in their soul that is about bettering their society. The modern leader has to look beyond self, be willing to risk themselves for the greater good and dare to then spend their time bringing the greater good out of people. You can’t have rank in that. I believe people come with a diverse set of gifts. Some people bring high intellect, but high intellect is not all we need; some bring heart. Some people bring persistence, because you can have high intellect and you can have heart, but you can’t persist. It’s bringing that together and synthesizing that that brings the best out. I believe you have to think a lot about the long legacy. I guess all of us do like a little bit of us to endure, but it’s not by keeping our space we endure. I believe that every generation has to be better than the last, which I think is something I picked up from being around East Indians. It’s the only way I can describe it. I believe I’ve heard it said by them. I’ve heard it in the ethos, that every generation must be better. I take one day at a time. I don’t have huge dreams about the future. I believe life is sweetest when you feel you know your purpose in your soul and you are being honest about pursuing it. I don’t have a lot of disappointments because disappointments are just opportunities to learn. Admit your mistakes because you make plenty. Work on your strengths and strengthen them and make sure that you understand your weaknesses. Be free to admit that you have real weaknesses. Admit your failures, because integrity is not about telling the truth when you can. It’s about telling the truth at all times. It’s not convenient truth; it’s inconvenient truth, the kind that shows you up as making mistakes, shows up your frailties and weaknesses. That’s when you know integrity. And we could do with a heavy dose of that in our public life.

|

Poverty shaped him, embedded a value system not driven by money, though he is wealthy; a rejection of elitism, though he is among the elite; a distaste for authoritarianism, though he runs a mighty empire.

Poverty shaped him, embedded a value system not driven by money, though he is wealthy; a rejection of elitism, though he is among the elite; a distaste for authoritarianism, though he runs a mighty empire.