|

June 2018

Issue Home >>

|

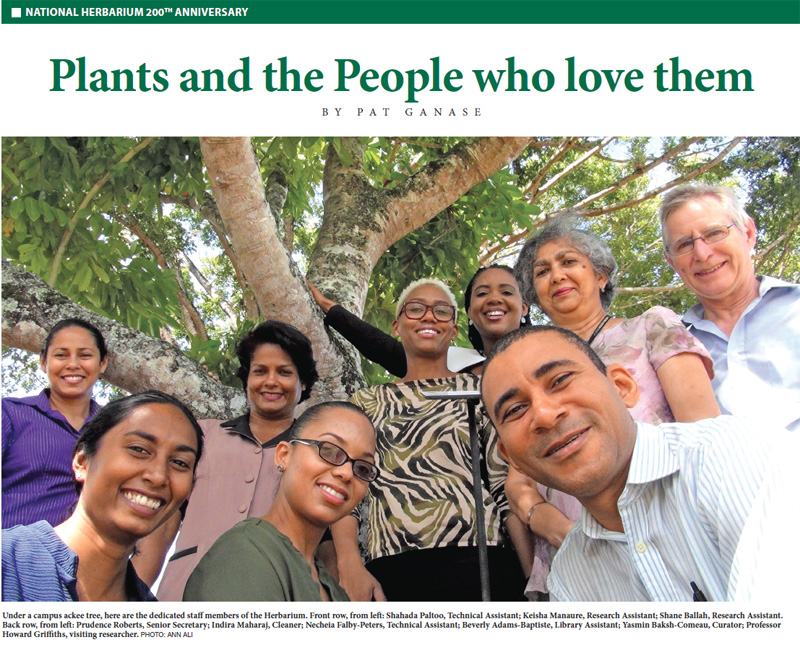

The Royal Botanic Gardens in Port of Spain was established in 1818. It was a living site for the study of trees, particularly those that were relocated here from around the tropical world. The Gardens’ museum partner is the National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago. Two centuries of plant collections – one living, the other dead – were celebrated on May 22, 2018, World Biodiversity Day. Yasmin Baksh-Comeau talks about how the two collections complement each other.

Yasmin Baksh-Comeau was appointed Curator of the Herbarium in 1980. She had recently graduated from the UWI in Botany and Chemistry: it was her first job, became her only job, and fostered a lifelong passion, a love of living trees and the comforts they provide. Even as relics, the trees are useful. As Baksh-Comeau wrote succinctly in a recent issue of UWI Today, the museum collection serves a valuable purpose, “using the dead to inform the living.”

“Taking on the role of curator was a challenge. There was one room with tables and cupboards. The collection was in various stages of decay. There were boxes of unprocessed, unmounted specimens. Some of the mounted specimens were as old as 1842; everything was deteriorating. I had one technician inherited from the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture (ICTA).

“What’s the use of a herbarium? This is an archival collection of plant specimens. These samples say ‘I was here. I existed.’ How do we know the dodo existed? We have pictures or relics; we have something that is the proof of existence. That’s what these specimens represent.”

Baksh-Comeau refers us to Vicki Funk’s (US National Herbarium) treatise 100 Uses For An Herbarium: “Herbaria, dried pressed plant specimens and their associated collections data, ancillary collections (e.g. photographs) and library materials, are remarkable and irreplaceable sources of information about plants and the world they inhabit. They provide the comparative material that is essential for studies in taxonomy, systematics, ecology, anatomy, morphology, conservation biology, biodiversity, ethnobotany and paleobiology, as well as being used for teaching and by the public.” Baksh-Comeau refers us to Vicki Funk’s (US National Herbarium) treatise 100 Uses For An Herbarium: “Herbaria, dried pressed plant specimens and their associated collections data, ancillary collections (e.g. photographs) and library materials, are remarkable and irreplaceable sources of information about plants and the world they inhabit. They provide the comparative material that is essential for studies in taxonomy, systematics, ecology, anatomy, morphology, conservation biology, biodiversity, ethnobotany and paleobiology, as well as being used for teaching and by the public.”

The National Herbarium in St Augustine, Trinidad is one way of accessing the history of our islands. Baksh-Comeau says, “By the time the Spanish arrived, the vegetation of these islands was already changing. Colonisers brought in plants that transformed the original landscape; of course, it was all for economic gain.

“The Herbarium was established alongside the Royal Botanic Gardens, which was a teaching site. It was relocated to the ICTA in 1947, and eventually was left to the UWI as custodian. It was Professor Ken Julien, then Chairman of the Scientific Advisory Council, who recognized it as a most valuable resource and recommended that the Government of Trinidad and Tobago take over its financial support as a ‘national asset’ with UWI as the custodian. We became the National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago (registered as TRIN in the Index Herbariorum ) in 1973.”

Skipping 30 years, Baksh-Comeau says, “In 2005, the UK government funded a Darwin Initiative Project, awarded to Oxford University to collaborate with the Herbarium at UWI and the Forestry Division. They introduced us to the RBS (Rapid Botanical Survey) method. Trinidad and Tobago was the first Small Island Developing State (SIDS) to implement this method. We collected approximately 25,000 specimens in two years. It was the most intensive and extensive survey ever undertaken on the islands, and combined with the herbarium historical and modern collections, resulted in the identification of ‘botanical hotspots’ of high conservation value on our two islands. The herbarium collection was digitized and the RBS samples databased and uploaded into the BRAHMS (Botanical Research and Herbarium Management System) software and sent electronically to the Oxford University website. It was a pioneering project and represents a model of collaboration.”

The survey resulted in the 2016 publication, “An annotated checklist of the vascular plants of Trinidad & Tobago with analysis of vegetation types and botanical hotspots.” This project involved plant ecologists Dr William Hawthorne and the taxonomist Dr Stephen Harris, both from Oxford University, the full staff of the TRIN Herbarium, along with a team of volunteers, 29 forest officers, who assisted Shobha Maharaj, Research Officer, who conducted the survey of 240 sites from which over 22,000 specimen samples were identified. The “checklist” may be purchased online through the link: http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/article/view/phytotaxa.250.1.1 or from the limited number of printed copies available at the Herbarium.

By the numbers, according to Baksh-Comeau, a total of 3,639 species were recorded, of which 108 are endemic, 2,407 indigenous and 1,222 exotic. Indigenous plants are those found in specific regions or ecosystems as the result of natural processes; endemic species are exclusively native in a particular place or ecosystem. Pride of place in the Herbarium is occupied by the special collection of Theobroma and Herrania species inherited from the Anglo-Columbian Cocoa Collecting Expedition of 1952-53 to the tributaries of the Amazon and Magdalena rivers in the Andes by staff from the Cocoa Research Scheme of the ICTA.

We may be rich in the trees that have taken root here over the years: a reflection of all the people who came to populate the Caribbean. But Baksh-Comeau’s response to a question about what’s really native to our islands in our daily diet is a revelation: “Shadon beni,” she says, “may be the only native (named by those who came from India, bandhania) plant. And balata.” Almost everything else that we eat came from elsewhere.

The Darwin Project 2006 to 2008 coincided with the refurbishing of the Herbarium. It was an intense double workload with satisfying results: the Herbarium now features state-of-the-art facilities, microscopes and photographic equipment, climate-controlled storage lockers, and a library. Beverley Adams-Baptiste, the librarian, who joined in this period, welcomes visitors whether their interest is scientific or merely curious. Among the artifacts in this library are watercolour paintings of common Tobago plants drawn by Major Charles Dalton Grigson between 1946 and 1948.

“Today, we have over 50,000 specimens. I think we have covered most of the vascular (ferns and flowering plants) plants in Trinidad and Tobago in the collection. We are looking at a mycological (fungi) collection next.” Baksh-Comeau is concerned that the Herbarium needs a new expansion: more space for research and outreach, and certainly for public engagement and exhibits, is required. Her vision, however, goes beyond the museum walls. She advocates for living collections all over our two islands. “Today, we have over 50,000 specimens. I think we have covered most of the vascular (ferns and flowering plants) plants in Trinidad and Tobago in the collection. We are looking at a mycological (fungi) collection next.” Baksh-Comeau is concerned that the Herbarium needs a new expansion: more space for research and outreach, and certainly for public engagement and exhibits, is required. Her vision, however, goes beyond the museum walls. She advocates for living collections all over our two islands.

“The trees here on the campus at the UWI - some of which may be decades even a hundred years old – should be a teaching collection. Many of them have created the settings for students’ social activity marking memorable occasions on campus – cool spaces for meals, quiet contemplation, courting, proposing – and should be cherished. Our task must be to foster and seed the greening of the urban landscape. Our campus should be a continuum of the Northern Range, the living heritage of appreciating and conserving our biodiversity.

“We started on World Biodiversity Day (May 22) with the ceremonial planting of two trees by the President of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, Her Excellency Paula-Mae Weekes, and our Pro Vice Chancellor and Principal, Professor Brian Copeland. At the same time, the label on one mature tree was re-installed by the Deputy British High Commissioner; this is symbolic and relevant since the new labels on all the trees will bear QR codes which will link to the Virtual Campus Arboretum on the new herbarium website under construction.”

In mid-June, students from Hillview College, in collaboration with the UWI Biodiversity Society, will undertake the planting of 200 native trees on a degraded hill slope near the college premises. These trees will also be labeled in due course. It will be the pilot for getting many other communities involved. Baksh-Comeau is excited by the prospect of living trees and forests. She is grateful for the contribution of trees by the Herbarium volunteers, Dan Jaggernauth and George de Verteuil and the Forestry Division, saying:

“We need to bring all sectors of society to reforest the landscape, especially urban areas, in order to instill appreciation of trees and the value of biodiversity; in order to foster conservation and protection of the natural forest.”

|