|

|

|

|

June 2019

|

By the time Patricia Mohammed graduated from Naparima Girls’ High School in 1971, seeds of activism had already been planted. “My generation was optimistic, as well as visionary. We had a sense that we could change the world for the better.” After over four decades of teaching and research at The University of the West Indies, Professor Patricia Mohammed is reflective as she prepares for her retirement on July 31. She has led a distinguished and prolific career of pioneering feminist scholarship in the Caribbean-wide movement. “A renaissance thinker”, Mohammed has had a “catholic approach to education”, seeing all subjects as interconnected. She has a practical sensibility for the differences in disciplinary methodologies and theoretical positions, a trait essential to her strong performance in her decade-long role as Campus Coordinator and Director of Graduate Studies and Research at The UWI’s St. Augustine Campus. But before a career in academia was even a thought, a 17-year-old Mohammed had a revolutionary experience as a hospital worker. An old woman offered Mohammed money in exchange for medical attention, but she declined assuring her that it was her job to help. Mohammed earned a new sense of custodianship through encounters with the poor, and viewed the palpable lack of agency and imbalance of power they suffered as due for remedy. “I want to make the link between that and how I still treat students today,” she says. At this, I confessed she had left her imprint on me while supervising my undergrad Women’s Studies thesis two decades earlier. One day I showed up at Professor Mohammed’s office for our appointment. Let’s go outside, she said. She’d chosen a sunny spot on the concrete steps somewhere behind the engineering block, and thumbed through the document. I was touched by her empathetic response to the neatly bound mayhem disguised as academic prose. Kindly, she said that what I had was okay, but that I needed to “sharpen thought” and to think of the writing process as continually sharpening a pencil as one’s points became dulled with overwriting. It’s this pursuit of perfection that has led to some eminent feminist discourse where she would unravel inequalities faced by two women in her life. That they endured an abusive, alcoholic husband, or “old-style attitudes to Indian women”, and yet remained, was a tragic contradiction.

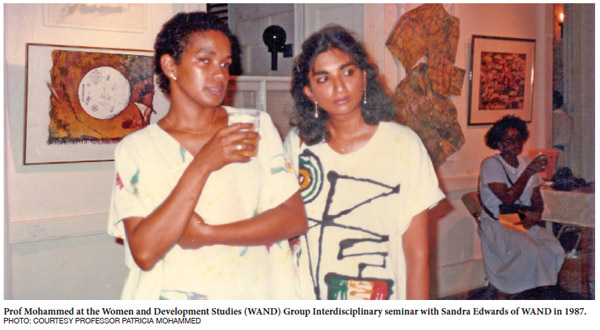

This was in 1975 “when the ideas had filtered in” from the global women’s movement and the UN First World Women’s Conference. Mohammed found a connection with the activism of Hazel Brown, who had started The Housewives’ Association of Trinidad and Tobago (HATT), and with Diana Mahabir, then a senator, and very vocal in women’s issues. This was the turning point. “I got involved in the People’s Popular Movement that created the Concerned Women for Progress as its women’s arm and the first second-wave feminist group in Trinidad; I became de facto one of its leaders. So I was very much an activist as well while doing a Master’s thesis on women — there was always the combination of the political and the social, and education.” As a Master’s student, Mohammed’s academic roadmap steered her towards receiving a Commonwealth Fellowship to work with Professor Kate Young at the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex. Young had just established the first Women, Men and Development Study course, requiring Mohammed to work as a research assistant for a year. During this time in the UK, she worked shoulder to shoulder with some 30 international scholars. “This was a very rich period of movement, so my feminism and my outlook which was always regional, went international,” she says. Mohammed inevitably crossed paths with people who would become deeply influential, personally and intellectually. A 15-year partnership that counts as a major intellectual influence on Mohammed did not emerge out of academia, she notes with some irony. She praises the friendship as a training ground for critical thinking and debate, and for how it led to new pathways of learning. Similarly, her marriage of over 25 years to British-Caribbean artist Rex Dixon has been the second most learning experience of her life, surrounded every day by his knowledge and practice of painting. Among a list of inspiring academic colleagues, Mohammed names Professor of English Literature Gordon Rohlehr, for his “capacity to engage in the subject matter and to travel with it”, and Professor of History Bridget Brereton, whose “detailed, methodical approach and economy of words” she admires.

Broadening the imaginative capacity was a conduit to seeing beyond academic arguments and to sifting through and surfacing with new ideas. She said that this process was an intuitive one, necessary to provide balance, perspective and feeling. Her movement to film-making in which she has made, among others, two award-winning films “Coolie Pink and Green” (2009) and “City on a Hill” (2015) and book Imaging the Caribbean: Culture and Visual Translation (2009) were products of a similar aesthetic sensibility of history. And for her final research role at The UWI, Professor Mohammed would also return to that instinctive process of combining logic with creative storytelling. She conceptualised The UWI Visual Heritage Exhibition, researched and developed over eight months with the skilled hand of Research Assistant Chelsea Seetahal. Mohammed undertook the task as “a gift for the university” and as an “attempt to leave a footprint both for the heritage (of The UWI) and the growth of Graduate Studies”.

The photographic exhibition was presented in two sections, located in the main corridor of the Lloyd Braithwaite Student Administration Building, and the offices of Graduate Studies and Research, respectively. Professor Mohammed offered parting words for The UWI’s continued success as a repository for artistic and historical record and scholastic identity: “I would like the university to be conscious of the feeling of awe it must create for its students, staff and visitors and to ensure that its beauty is maintained and to build on that. For example, create a design for our main sidewalks with our own imprint of tiles that tell this story, so when you walk in the university, you walk into a compound that already has a signature of the space; it brings a whole different feel to that journey.” Sabrina Vailloo is a writer, editor and certified events coordinator. She’s currently head of branding at a local start-up. |

Dancing women holding flowers. Placard slogans for peace. Fists flying high in protest. The imagery of the Flower Power era and the local Black Power Movement had a seminal effect on a generation. And one teenaged girl from south Trinidad watched with eyes wide open.

Dancing women holding flowers. Placard slogans for peace. Fists flying high in protest. The imagery of the Flower Power era and the local Black Power Movement had a seminal effect on a generation. And one teenaged girl from south Trinidad watched with eyes wide open. “I was always confused about how both things could coexist. It shaped in me an understanding how the nuances of gender and gender relations couldn’t be just cut through with slogans or with divisions like ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’.” Compelled “to make sense of how Indians negotiated their gender relations”, Mohammed would produce two academic breakthroughs, an MSc in Sociology in 1987 with a demographic study of women in education in Trinidad and Tobago, and later on, aPhD thesis, titled Gender Negotiations Among Indians in Trinidad 1917-1947 (2002).

“I was always confused about how both things could coexist. It shaped in me an understanding how the nuances of gender and gender relations couldn’t be just cut through with slogans or with divisions like ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’.” Compelled “to make sense of how Indians negotiated their gender relations”, Mohammed would produce two academic breakthroughs, an MSc in Sociology in 1987 with a demographic study of women in education in Trinidad and Tobago, and later on, aPhD thesis, titled Gender Negotiations Among Indians in Trinidad 1917-1947 (2002).  In the Netherlands, the five-year PhD research period was a “very intensive and lonely experience”. At the same time, Mohammed wanted to transcend from left-brained logic to right-brained creativity. Reaching out for balance, she found it in art, a perennial passion. After attending her exhibition, Mohammed attached herself to a Dutch artist who paid her a small stipend. By the time she left the International Institute of Social Studies, she was able to put on her own full exhibition.

In the Netherlands, the five-year PhD research period was a “very intensive and lonely experience”. At the same time, Mohammed wanted to transcend from left-brained logic to right-brained creativity. Reaching out for balance, she found it in art, a perennial passion. After attending her exhibition, Mohammed attached herself to a Dutch artist who paid her a small stipend. By the time she left the International Institute of Social Studies, she was able to put on her own full exhibition. The exhibition, launched on May 24, is a celebratory nexus of The UWI’s architectural heritage, colonial and post-colonial history, student life in evolution, and many other transformative events that have shaped the institution from 1922 to present day.

The exhibition, launched on May 24, is a celebratory nexus of The UWI’s architectural heritage, colonial and post-colonial history, student life in evolution, and many other transformative events that have shaped the institution from 1922 to present day.