We are in the Zoology Museum at UWI St Augustine’s Department of Life Sciences (DLS), and curator Ryan Mohammed is explaining just how “giant” was the now extinct giant armadillo known as glyptodont. We are in the Zoology Museum at UWI St Augustine’s Department of Life Sciences (DLS), and curator Ryan Mohammed is explaining just how “giant” was the now extinct giant armadillo known as glyptodont.

Mohammed says, “we are talking about an animal the size of a Mini Cooper.”

Yes, once upon a time giant animals roamed Trinidad: armadillos the size of cars, ground sloths 20 feet tall. How long ago? Estimates range from hundreds of thousands to millions of years, long enough for time and weather to erase them from history. But Trinidad is blessed with a powerful preserving agent – tar.

“The value of tar pit or asphaltic fossils in the Neotropics is immense because fossils do not preserve in this environment typically,” says Aisling Farrell, Collections Manager at the La Brea Tar Pits Museum in Los Angeles, California. “So having them beautifully preserved in asphalt is exquisite.”

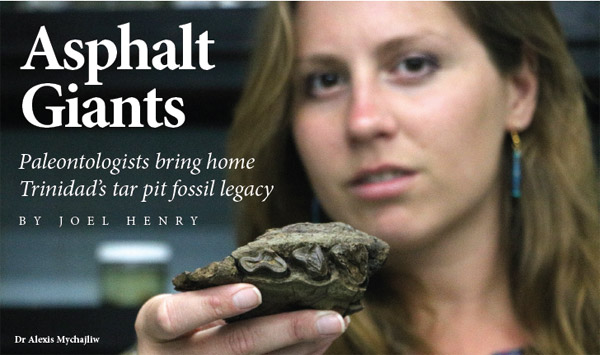

Aisling and her colleague, Dr Alexis Mychajliw (postdoctoral fellow at the Tar Pits Museum) know a great deal about tar pits, fossils, and the natural world of the prehistoric past. And, thanks to their efforts UWI St Augustine now knows a great deal more about Trinidad and Tobago’s. They have used their international network of paleontologists to recover fossils unearthed in Trinidad and taken abroad from as far back as the 1920s, returning fragments of a historic legacy that may go as far back as the Ice Age.

They also came to teach.

From La Brea to La Brea

“In the scientific literature, when they talk about tar pits they focus on Los Angeles, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela, but there is always at least one sentence in the paper on Trinidad. There’s always been this general awareness that Trinidad had material but nobody went out and investigated,” says Mychajliw.

Her moment came in July 2018 when the Latin America and Caribbean Congress for Conservation Biology (LACCCB) was held in Trinidad at the St Augustine Campus.

They met with then DLS Head Dr Adesh Ramsubhag to discuss Trinidad’s asphaltic fossils and visited local sites. After their return to the US they reached out to their community of paleontologists and museums and found a host of materials that were unearthed through oil exploration work in the 1920s, 30s, 50s, 80s and 2001. The initial plan was to have them shipped directly to UWI.

“Then it changed to ‘why just send it?’,” says Mohammed. “We asked them to come and help us build capacity here to do research.”

So in April 2019 they returned to Trinidad, bringing crates of asphaltic materials taken from sites such as the Forest Reserve and Pitch Lake.

Mohammed says, “they have really done yeoman service for the University and the country by being able to track these things down and bringing them home.”

On our visit to the Zoology Museum we saw a number of fossils separated into three different boxes based on how much information was known about them. Apart from the glyptodont remains there was a massive tip from the claw of a ground sloth. The size of a tablet computer, its owner must have been truly gigantic. There was also a row of near-perfectly preserved teeth and part of a jaw that is believed to have belonged to a llama. Yes, llamas in Trinidad.

Mychajliw says: “The thing about Trinidad is its biodiversity. It used to be part of South America until recently so it is this really interesting experiment of when you turn a continent into an island. And on top of that Trinidad is that gateway between South America and the Caribbean.”

She describes the very different world of the prehistoric past: “People moved through here and animals moved through here. This is a great window to understand how the Caribbean came to be. You have giant armadillo specimens that evolved in South America in isolation for millions of years. Then if we had something like a llama or carnivore, this would have had to come from North America with the landbridge.”

More museum, more paleontology

The tar pit fossils are an exciting discovery at an exciting time for the University. And the DLS understands the significance.

“We’ve gone into the deep sea,” says DLS Head of Department Dr Judith Gobin, referencing her work in underwater exploration. “Through Dr (Shirin) Haque’s (Senior Lecturer in Astronomy in the Department of Physics) work we’ve gone to the stars. And now this extraordinary find takes us deep into the core of ecological time.” “We’ve gone into the deep sea,” says DLS Head of Department Dr Judith Gobin, referencing her work in underwater exploration. “Through Dr (Shirin) Haque’s (Senior Lecturer in Astronomy in the Department of Physics) work we’ve gone to the stars. And now this extraordinary find takes us deep into the core of ecological time.”

Gobin sees the tar pit fossils as a “gold mine” that UWI must recognise. Her vision is an expansion of the Zoology Museum to better showcase its extraordinary collection of animals and insects.

“My approach, which I voiced to the Deputy Principal (Professor Indar Ramnarine), is that I would like him to consider locating space for us. Or if we could, extend our existing space. If they will allow me to extend the museum I will seek out external funding to enhance it,” she says.

Gobin adds, “We want to let the general public know this exists and that it is an incredibly valuable part of our heritage.”

But housing and displaying the items are only part of the agenda. During their visit to Trinidad the team from La Brea Los Angeles also taught a three-day short course to a group of over 40 that included students and members of the public. It involved class work, a field trip and excavation exercise, and finally laboratory work.

“Almost 50 people came on a Saturday at 9am,” says Mychajliw of the field trip. “People volunteering their time was really amazing.”

Mychajliw and Farrell volunteered their time as well. Apart from everything else they did during the trip, Mychajliw also gave a public lecture at the campus, titled “Tar Pit Time Capsule: Unearthing Trinidad’s Ice Age Giants”.

“I really want to see a community of paleontologists develop here,” she says. “I think Trinidad could be a place on the cutting edge of this type of research. The museum here is absolutely wonderful. It has the right facilities to do that type of work. It has the right people here to support the students. So my ultimate goal is to see students take ownership of the material and run with it.”

It’s a sentiment shared by DLS, not just to establish a teaching and research agenda for these near-magical creatures from the distant past, but to create a national understanding of their significance to our society.

“Now the work begins,” says Dr Gobin.

|