|

|

|

|

March 2013 |

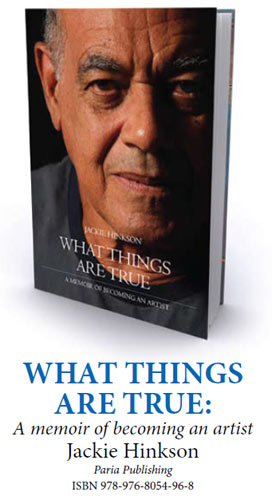

“Standing on the sidewalk across from the shop, I look up to the family quarters under the gables. The fenestration of jalousies and windows overhangs the sidewalk outside the shop. Bicycles lean on wooden posts.” It is a Chinese shop, one of many he has visually recorded as part of the “vernacular heritage in architecture,” that abounded in Trinidad. Capturing nesting places – homes, churches, shops, trees – has been one of the passions of Jackie Hinkson. Images of these formative spaces are vividly evoked in “What Things Are True: A memoir of becoming an artist” as he meanders through those early years. Hinkson is an accomplished artist: he draws, he paints, he sculpts, and his work has received widespread acclaim. From the incandescence of the book’s prose it would not have been surprising to find that he was a remarkable writer as well. But he has been quick to make it clear that the book was “ghost-written” by a lifelong friend, who turns out to be the brilliant biographer, Arnold Rampersad. The two collaborated over a year, and after dozens of interviews had been transcribed, Rampersad shaped and drafted what Hinkson would then edit to his satisfaction. The book is elegantly bound, printed in the graceful font, Centaur, and it is strewn with sketches from what must be a massive collection – a charming combination for a reader who loves the feel of the turning page. Normally, I read quickly, but I found myself slowing down, savouring sentences and retrieving others so I could revisit them. At some point, the reason became clear. The book is written the way an artist must see his subjects. The exquisite detail can only have been harboured in a mind trained to record it carefully; for reproduction. The description of the Chinese shop is just one of many that either adds layers to dusty memories or creates sparkling new images. Rampersad sees biography through all the strands that bind a life together, so one can imagine him coaxing memory out of mind, and expertly giving it texture and hue with just the rightly nuanced questions. It is something of a coming of age book, for man and country, bringing intimacy to the growing pains borne at 21 Richmond Street in Port of Spain and later, at Académie Julian in Paris. Hinkson’s account of his childhood dreams and miseries, alienating days at QRC, his forays into existentialism and Cobo Town, emerging friendships, and his eventual release into the Parisian wild, simultaneously render a portrait of the period while tracing the persistent inner turmoil. And as the pages turn, the deft lines add up and the portrait of the artist begins to emerge, and in the gently applied strokes one can feel his almost perpetual bewilderment fading as he becomes more comfortable in his skin. “Sometimes I wonder if my devotion to art isn’t akin to my father’s tendency to compulsiveness. I hold up small pieces of the world around me to the light and I see things that most other people apparently don’t notice. I try to put those pieces of the world down on paper or canvas, or occasionally in wood sculpture. I look for forms of truth, of self-revelation and of revelation beyond the self. I look for perfection, if you will. I seek to distill the essence of the world as I know it.” The memoir provides a social history, revealing the mores of that time; how the artist, the lawyer, the doctor, the athlete was ranked. And the conditions: where but the public library could one find anything to read on art and artists? And what it felt like after finding Cézanne and just knowing that life without art would be meaningless. “As far as I knew, none of my schoolmates valued art. Distinction came at QRC and its rival schools through the efforts of athletes and ‘bright boys.’ Artists simply didn’t count in the scheme of things. Male artists were also likely to be ‘hens’ (so some tough boys called other students in order to disparage their sexuality). So where was I to turn to express my budding love of art, and my desire to become an artist?” His QRC friendship with Peter Minshall would be significant here (In 1961, with Minshall, Pat Bishop, Alice Greenhall and Arthur Webb, he would be part of the exhibition, “5 Young Painters”.) but overall, he didn’t find it at QRC and it was not on the syllabus at either Progressive Girls or Tranquillity where he taught briefly in the early sixties. It was later, in a much muddled route to take up a scholarship of sorts, that he found himself in Paris and discovered a new way of seeing that he began to feel himself an artist. But homesickness lunged so fiercely at him that, despite misgivings, he made no effort to prolong his yearlong stay. “Never had I enjoyed so much free, subsidised time in which to draw and paint. Another year might have taken me to new levels of competence and skill. I still suffered from pangs of doubt about my art. My instructors still seemed to see nothing out of the ordinary in my work.” In Trinidad again, he went back to teach at QRC and reconnected with Minshall, who had returned from London. Soon, he was offered a five-year fellowship to study art in Canada. One day, the influential artist, Sybil Atteck said something to him that could be relevantly said today. She told him that he would learn a lot in those five years, but when he returned he would have to “unlearn” much of it. The book moves along languidly, lingering on those “becoming” years, but it fairly canters towards the end, leaving one wishing for more. As the front door is being pulled in, we are allowed a glimpse of the married artist, now a parent, at home in Trinidad, still ruminating on the dilemmas of art. “I was amazed and continue to be amazed that so many in the world of art do not see beyond surface subject matter, believing that full meaning in a work stops at literal surface symbolism. There must be no nuances. “I knew that as I went forward with my life in Trinidad and Tobago, I would have to deal ceaselessly with this tension and hostility about politics and race, about radical changes in our values and traditions. I would have to confront these changes and interpret them in my work, but in my way and within the notion of art that I had developed during the first twenty-eight years of my life.” Yes, the book is that too, a guide to the life of the craft. Let the artist beware. Artist Donald Jackie Hinkson (2011) and Professor Arnold Rampersad (2009) have both been conferred with honorary doctorates by The UWI. Permission was sought to disclose Professor Rampersad’s contribution to the book. |

“The counter top is smooth and shiny from years of use. The shopkeeper deftly shovels flour or sugar into brown paper bags on the curved brass bowl of his scale. Before one is quite certain about the weight, he twirls the bag and secures its contents. Then he slips the pencil stub from behind his ear and adds up the bill. Above his head hangs a shiny curling tape that traps flies…

“The counter top is smooth and shiny from years of use. The shopkeeper deftly shovels flour or sugar into brown paper bags on the curved brass bowl of his scale. Before one is quite certain about the weight, he twirls the bag and secures its contents. Then he slips the pencil stub from behind his ear and adds up the bill. Above his head hangs a shiny curling tape that traps flies…