|

|

|

|

May - June 2008

|

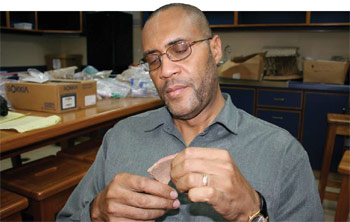

Q & A : Dr. Basil ReidUWI lecturer and archaeologist, takes a critical look at our pastby Anna Walcott-Hardy Q: Do you think our West Indian history books are accurate especially in terms of the reporting on the Amerindians, their way of life, government, culture, society etc? A: Yes and No. Some books provide useful and reasonably accurate information on Amerindian lifeways but the majority are grossly inaccurate as they tend to “lump together” most of the major Amerindian groups in the Caribbean as either “Arawaks” or “Caribs.” Using these broad categories does not adequately reflect the multiplicity and social complexity of the Amerindian groups that existed in the region before and after Columbus. There are also major inaccuracies concerning the naming of groups of people as well as their geographical distributions. While doing research for my book Popular Myths About Caribbean History, I reviewed several text books currently being used for teaching Caribbean history in secondary schools and noticed many had these glaring inaccuracies. I partially blame serious scholars like myself for this privy to the most current information on the Caribbean native peoples, we have been busy talking to among ourselves at conferences and writing esoteric papers for often inaccessible journals rather than writing for popular audiences. The book Popular Myths About Caribbean History is an attempt on my part to correct this shortcoming and it seeks share current information with the general public, in simple, non-academic language. Q: Is there a particular case study that you found to be quite revolutionary, a breakthrough? A: Recent information that the Archaic peoples in fact produced pottery was quite revolutionary as for decades many Caribbean archaeologists, including myself, assumed that the Saladoids were the first potters in the Caribbean. The Archaic people, also called the Casimiroids and the Ortoroids, migrated from Central America and South America approximately 7000 to 5000 years ago, colonising much of the Caribbean until the arrival of the Saladoids in 500 B.C. The Archaic people were generally classified as preceramic but pottery found at their sites in Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands suggest that they were also potters. In Caribbean archaeology, pottery is closely associated with farming. Interestingly, there is emerging evidence that the Archaics were also engaged in plant domestication. The Archaic people also inhabited Banwari Trace in southwest Trinidad. To date, no pottery has been found at Banwari Trace. But given that the site is still very much under-researched, we should keep an open mind to possible discoveries in the future. Q: Do you think we are doing enough locally and in the Caribbean to preserve our sites and archaeological discoveries? A: To an extent, there are efforts to preserve our sites and various archaeological discoveries. Throughout the Caribbean, there are a number of heritage management agencies such as the National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago, the National Museum of Trinidad and Tobago, the Barbados Museum and Historical Society, the Barbados Trust, the Jamaica National Heritage Trust, the Institute of Jamaica, the St. Lucia Archaeological and Historical Society and the national Archaeological Museum of the Netherlands Antilles (NAAM). Several Caribbean territories have enacted laws aimed at protecting sites and monuments. In Trinidad and Tobago, for example, the National Trust Act offers some measure of protection provided that the site or historic monument is designated as a property of interest. The protection of underwater archaeological heritage in Trinidad and Tobago was given attention in 1994 with the passing of the Protection of Wrecks Act. There is also a Cabinet-appointed National Archaeological Committee that advises the Minister of Culture on archaeologically-related matters. Despite all of these useful legislative and institutional frameworks in Trinidad and Tobago and elsewhere in the Caribbean, sites are still being destroyed or compromised due to urbanisation, agriculture or industrialisation. This problem is certainly commonplace throughout the Caribbean and perhaps one of the ways of to curtail the problem is to ensure that the laws are more effectively policed. This may be achieved by sensitizing local communities to their heritage through the formation of county or parish heritage groups throughout the region. Providing developers with tax credits can be a useful incentive to encourage them to protect archaeological sites on their private properties. We also need to train more archaeologists to satisfy local needs rather than becoming so dependent on overseas expertise. By so doing, we would create a local cadre of archaeologists available for rescue archaeology, whenever sites are threatened by development. Geoinformatics can also be used to map sites that are being threatened as well as identify those that are neither visible nor accessible because of thick vegetation or rugged topography. These are just some of the ways in which we could more effectively protect and preserve our archaeological heritage. Q: What important discoveries have been made in Trinidad and Tobago? A: The discovery of the Banwari Trace in southwest Trinidad as well as the discovery of Banwari Man by members of the Trinidad and Tobago Historical Society in November 1969 can be cited as important iscoveries. Radiocarbon dates indicate that Banwari Trace was inhabited around 5000 BC, making it the oldest in the Caribbean. Another important discovery was the Saladoid site of Gandhi Village in south Trinidad. Although not many artifacts were found there by my students in 2003 and 2006, the site, given its hilltop location, nevertheless provided us with useful insights into the defensive nature of some pre- Columbian sites in Trinidad. Q. Where is Banwari man housed ? A: The remains are housed in the Museum of the Life Sciences Department. Persons interested in viewing the remains may contact Ms. Savitree Rattan; telephone number 662-2002 extension 2237. Q: How many digs are you currently involved in? A: At present, my digs are usually conducted when I teach the course: Research Methods and Techniques in Archaeology…and that the fieldwork component of that course usually takes place around March or April of each year. When I started teaching at U.W.I., I was very active in the field. I organised major projects at Blanchisseuse (Trinidad) and Lover’s Retreat (Tobago) between 2003 and 2005. However, I have decided to limit field activities for the time being in order to complete a number of publications that have been hanging for a while. Once, I get those publications out of the way, I will be going back into the field for more primary data, which in turn can be used to fuel new research publications. Q: What future projects are you involved in at UWI? A: I am looking at the possibility of working collaboratively with colleagues in the Department of Surveying and Land Information in the teaching of Caribbean archaeology based on geoinformatics. The Department of History is considering the introduction of a Masters degree in Heritage Studies in September 2009 and I have been asked to coordinate this course. Teaching this course will require that I work closely with my colleagues at U.W.I., St. Augustine as well as those outside of U.W.I. This course will focus on heritage management, heritage tourism, cultural legislation, archaeology, museology, landscape studies and environmental issues etc. and should be of particular interest to heritage professionals, tourism professionals, museologists as well as archaeology, museology and cultural studies enthusiasts. I plan to become more actively engaged in research projects outside of pre-Columbian archaeology such as historic landscapes, parks and gardens, railways as well as the archaeology of the industrial era. The archaeology of Trinidad and Tobago and the Caribbean is far more diverse than people are sometimes led to believe as it extends beyond the pre-Columbian period into the more recent historical periods where the data are a lot more visible and in greater abundance. When these projects have jelled, I will be in a better position to speak more definitively about them. Q: Why did you decide to produce this book? A: Because I felt that there was the need to legitimize the application of geoinformatics within the context of Caribbean archaeology. The vast majority of archaeology publications based on geographical information systems (GIS), remote sensing, aerial photography and other geoinformatics techniques, have tended to focus very heavily on North America and Europe with scant regard being paid to the Caribbean. This has been the situation for years despite the fact that Caribbean archaeologists have increasingly been employing geoinformatics techniques in their research projects and despite the fact that geoinformatics has been used worldwide for over 20 years. In the past, there were a handful of papers published on the use of geoinformatics in Caribbean archaeology. These were published as chapters in the Proceedings of the International Association for Caribbean Archaeology (IACA) rather than as edited chapters in an international publication like Archaeology and Geoinformatics: Case Studies from the Caribbean. This book is therefore an important milestone as it showcases to both regional and international audiences, the important work that is being done by Caribbean scholars. Q: What is geoinformatics and is it used at UWI? A: Geoinformatics pertains to the application of geographic information systems (GIS), remote sensing, aerial photography, photogrammetry, cartography, global positioning systems (GPS) and geophysical surveys. The Department of Surveying and Land Information at UWI, St. Augustine provides training in the judicious application of these techniques. I am sure that individual lecturers in other departments at UWI use geoinformatics in their various research projects. I received my geoinformatics training at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida (U.S.A.) where I did my Ph.D. in anthropology. Q: Why should we look at our history and these artifacts from a regional perspective? What are the benefits? A: A regional perspective is not only important, it is also absolutely necessary as it provides us with opportunities to compare and contrast the histories of Caribbean territories. For example, while it is useful to study individual sites such as the Saladoid sites of Blanchisseuse and Gandhi Village in Trinidad, unless we view these sites within the context of other Saladoid sites found elsewhere in the Caribbean, such as those in Montserrat, Antigua and Puerto Rico, then we will be unable to fully explore issues of migration, trade networks, community organisation and settlement atterns from a regional perspective. Being engaged in research from a regional context also brings us in contact with several colleagues throughout the Caribbean and outside the Caribbean, which in turn facilitates fresh perspectives, new lines of enquiry and a better research product in the end. |