|

|

|

|

May 2011

|

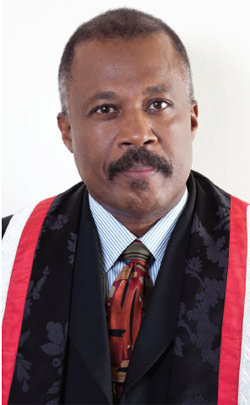

By Professor Hilary Beckles

The mandate of The University of the West Indies is consistent with this pedagogical understanding. It was established in 1948 to serve a very specific process: the emergence of a post colonial consciousness within Caribbean civilization. It was agreed by its founding thinkers, that despite the political balkanization of the region, caused by multiple imperial trajectories, a unifying historical process had created coherent cultural experiences that expressed themselves as an undeniable civilization. All agreed, furthermore, that a university, regional in scope and ideology, would best enhance this erupting empire of the mind that was countering the dominant vision of communities as home to servile labouring hands. In addition, the historians among the founders emphasized that this common, cultural legacy was crafted upon an indigenous cosmology that had long imagined the region as a common survival space – a sea warmly embracing a settled sense of self, despite its dramatic turbulence and turmoil. Eric Williams especially, was insistent: a regional university should be created embedded within a nativist Caribbean epistemology. Nothing else would suffice! It was not simply Williams’ persuasiveness that won the day. After all, he was speaking to a gathering of believers long converted to the philosophy of a singularity of sea and society. To this end the proclamation that called into being the regional university was not prophetic, but an expression of a common sense. The Caribbean was forged against a background of native genocide, African enslavement, Asian indenture, and is determined to rise from this colonial rubble as a unified force of familiarity and, hopefully, family. UWI, then, was launched as a missile into a self-possessed future with a distinct mission: to conquer colonialism, transcend imperialism, and liberate the Caribbean imagination. This mission is far from complete. Caribbean unity remains the vision of most inhabitants despite the persistence of a parading parochialism. Citizens increasingly are insisting upon the right to live in the Caribbean as their home though divisive governance has institutionalized the celebration of segregation that has no historical integrity and discernible future. The region’s politics, as a result, is best characterized as crippled by the unhappy circumstance of State versus Society that problematizes the journey to singularity. At no moment in the conception of The UWI was it imagined that the roots of five hundred years of European imperialism would wither and die within less time, or that the emerging mentalities of postcolonialism would possess abundant and persistent passion to drive the project. It was understood that ebb and flow, advance and retreat – the dynamics of historical change and continuity – would be a continuing feature of transformation. The lessons of the legacy of Caribbean liberation had shown this much, and The UWI would be subject to these laws. Men and women of commitment to the ancestral vision would come and go, while The UWI navigated this turbulent sea. This much I understood on becoming a part of the University’s senior management over 15 years ago. There I ‘roots’ with such unwavering men and women – Alister McIntyre, Rex Nettleford, Elsa Goveia, Keith Hunte, Sonny Ramphal, Bunny Lalor, Compton Bourne, Max Richards, Woodville Marshall, Roy Augier, Marlene Hamilton – a powerful intellectual force harnessed by an activism of regionalism. And it was all very personal. These were citizens who loved their Caribbean – all of it – and were giving their lives in its service. Their passion was devoid of parochialism, and enhanced by their desire for things Caribbean which they claimed as their very own. The work of The UWI as imagined by these stalwarts is still in its formative stages. In some ways it has only just begun. Preparations for another thrust are being laid. There have been a few setbacks, and some terrible errors, but the focus remains and the commitment no less certain. The ideal of the regional university also remains as fresh as it was articulated in the ’40s. Rationales for regional governance have changed, so too have the structures of economic institutions, and frameworks for resource management. But these are not central to the evolution of Caribbean civilization – that powerful binding sense of history that pushes against gravity in order to forge new depths for the restless and rebellious. Lloyd Best was in his richest vernacular vein when he insisted that The UWI should never succumb to the temptation of being a validating elite of academics. Rather, it should be a site of continuing resistance to the root causes of our impoverishment and marginalization. In this regard, he stands as a beacon along the way – as did Williams, Walter Rodney, McIntyre, Nettleford and others. The UWI, then, a site of resistance for the region, holds direct relevance for the future imagined. When, for example, our economic industries are threatened by global capitalism, in which corner of the region should the loudest voices of resistance be heard? When petty, domestic politics threatens to rip our fragile peace apart with racial and ethnic recklessness, where should we find an arena of opposition? When our youth are ravaged by locally produced and imported narcotics that enrich a few and outrage many, whose hearts and minds should rally the outraged? A regional university that transcends insular agendas is best suited to mend or remove broken fences and serve Caribbean society at the level of the collective interests of multiple communities. But there is more, of course, much more. Reading the time, and seizing the season, constitute the mandate of all high quality academic fraternities. As we examine this third, communications-driven phase of globalization, for example, we see that it is very much a contradictory process which we misread to our peril. On the one hand the global agenda speaks to openness and borderlessness. But on the other hand, we see that its fundamental building block remains the ‘nation-state.’ Powerful economies push for access to Caribbean markets while closing their political borders to our citizens. The politics of globalization promotes a dialogue of strong nations versus weak nations. The Caribbean nation, weakened because of its political fragmentation, cries out for UWI’s activism as imagined by its founders. Arguably, then The UWI has a compelling moment to demonstrate its pertinence to the needs of the people. Many cases can be made in support of its continuing relevance, and in all circumstances they serve to validate the visionary quality of its founders. A tertiary education revolution in the region is a prerequisite for sustained economic and social development. Currently, the English-speaking sub-region has the lowest enrolment rate in this hemisphere within the 18-30 age cohort. A shortage of relevant skills, more than capital, holds back the region on many fronts. The combined efforts of the regional university and national tertiary institutions represent the most efficient way to deal with this challenge. Spawning a new generation of national universities and colleges should be a top agenda priority for UWI, whose parenting role will be a vital resource in the years ahead. There are many aspects of this expectation that will require the mobilization of the collective research capacity of UWI. This is where it has a special niche as the regional embodiment and repository of our best efforts in search for new and innovative ideas to remove obstacles to development. Our challenges are regional in scope and nature and require collective engagements. Indeed, if we consider five pressing issues facing each Caribbean society – HIV/Aids, economic decline, political fragmentation, social decay, cultural stasis – each requires a regional answer best prepared by the institutions of The UWI. The roles and functions of national universities as strategic partners should be enhanced within the context of a regional university system in which The UWI, given its wealth of experience in building regionalism, has a continuing overarching mandate. Imaginative leadership within The UWI is a critical requirement. This is not a time in its journey for bureaucratic celebration and excessive administrative tinkering. It is a moment for a revitalization of intellectualism, and rededication to the activism of regionalism. Building consensus among regional stakeholders on the way forward will require research-based leadership strategies from the premier research institution. In this context the fidelity of UWI’s voice, and the integrity of its utterances, are crucial to envisioning the 21st Century Caribbean. Our region still wrestles with accepting institutions dedicated to its integrated identity. This suggests the need to aggressively assert the historical character of UWI. But such a legacy cannot be presented to the next generation as a right to be respected. Rather, UWI has to reinvent itself as a moral and cultural force within an ancestral stream that has brought us thus far safely, and remains forceful and fertile. |

Universities everywhere are established to serve nations. They are not expected to focus on a narrow self-perspective, or to commit to hegemonic sectional interests. Their mandate is to drive agreed processes of nation-building such as social tolerance and upliftment, economic development, cultural sophistication and political freedom. These objectives are critical to the enhancement of humanity and implemented within the imagined construct referred to as ‘nation.’

Universities everywhere are established to serve nations. They are not expected to focus on a narrow self-perspective, or to commit to hegemonic sectional interests. Their mandate is to drive agreed processes of nation-building such as social tolerance and upliftment, economic development, cultural sophistication and political freedom. These objectives are critical to the enhancement of humanity and implemented within the imagined construct referred to as ‘nation.’