|

|

|

|

May 2011

|

DIASPORA BONDS AND THE CARIBBEAN:

|

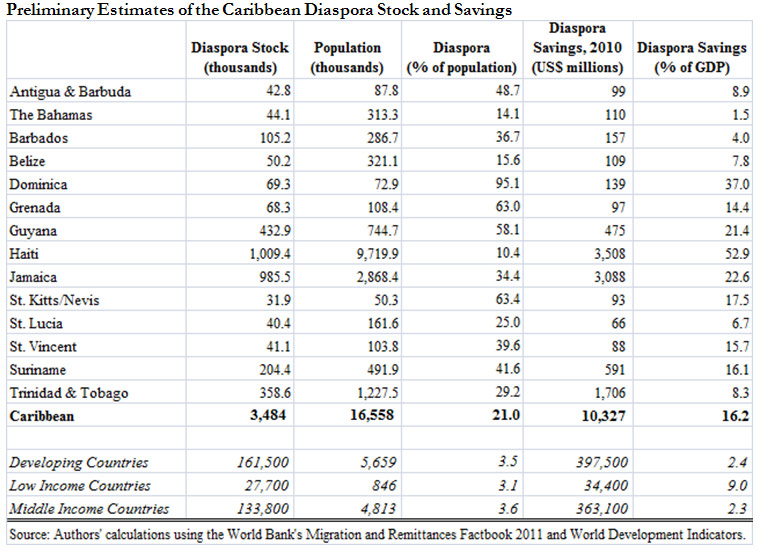

This is a synopsis of a paper to be presented at the International Conference on the Global South Asian Diaspora 2011, by Jwala Rambarran, Chairman, National Institute for Higher Education, Research Science and Technology (NIHERST) and Prakash Ramlakhan, Lecturer in Banking and Finance, UWI, St. Augustine. Although Caribbean countries are now starting to show some signs of recovery from the global economic crisis that began in the summer of 2007, many continue to encounter difficulties in obtaining external financing, a situation which jeopardizes their prospects for long-term growth and employment generation. Some Caribbean governments have reluctantly turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for financial support. Others have relied mainly on fiscal stimulus accompanied by borrowing on the regional capital markets, which further increases the risk of public debt distress. Inevitably, the Caribbean will need to consider and adopt more innovative and more stable forms of financing that target previously untapped investors. Using data from the World Bank’s Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011, the stock of the Caribbean diaspora is estimated at around 3.5 million people or more than one-fifth of the region’s population. This is not surprising since the Caribbean has one of the highest emigration rates in the world. Preliminary estimates place the annual savings of the Caribbean disapora at about US$10.3 billion or more than 15 percent of the region’s GDP. These estimates are based on assumptions that members of the Caribbean diaspora with tertiary education earn the average income of their top three host countries, that migrants without tertiary education earn a third of the average household incomes of the top three host countries, and that both skilled and unskilled migrants have the same personal savings rates as in their home countries. As expected, savings are higher for countries such as Haiti, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago that have more migrants in the advanced economies. Most of these savings are invested in the host countries of the diaspora, especially the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom. Indeed, if Caribbean countries were to design proper financial instruments and incentives, it is quite possible that a fraction of these US$10 billion in annual savings could be mobilised as investment in the Caribbean. Diaspora bonds are one such mechanism for tapping diaspora wealth. The governments of India and Israel have issued diaspora bonds, raising about US$40 billion, often in times of financial crisis. Lebanon and Sri Lanka have also issued diaspora bonds. Even Jamaica was at one time considering the issue of a diaspora bond. A diaspora bond is a retail savings instrument marketed only to members of a diaspora. Beyond patriotic reasons and the desire to contribute to economic development of their origin country, a diaspora investor may be willing to buy diaspora bonds at a lower interest rate than the rate demanded by foreign investors. This is a “patriotic” discount. Migrants are usually more loyal to their origin country than the average foreign investor in times of distress. By making available a reliable source of funding that can be tapped in both good and bad times, a diaspora bond market improves a country’s sovereign credit rating. Diaspora bonds also provide the opportunity for risk management. Migrants typically have better knowledge of their origin country and are less likely to worry about the risk of currency devaluation since they can often find other ways to send money back home. They are also less likely than purely dollar-based investors to be unduly concerned about the issuing country’s ability to make debt service payments in hard currency. In summary, the potential for disapora bonds in the Caribbean is enormous. In the wake of the devastating January 2010 earthquake, Haiti requires substantial sums to fund its reconstruction effort. International donors generously pledged aid to help build a better Haiti, but actual disbursements have been slow, stymieing the economic recovery process. If the million-plus Haitian diaspora were to simply invest US$500 each in diaspora bonds, the resulting sum of US$500 million would go a long way in helping to finance spending on relocation of families, education, energy and transport infrastructure. Part of the incentive for such investments by the Haitian diaspora would come from patriotism and part from higher returns. A five percent tax-free US dollar interest rate, for example, is far more attractive to Haitian investors who are getting close to zero interest rate on their deposits. Apart from the Haitian diaspora, the pool of potential investors could even be expanded to include foreign individuals and charitable institutions interested in helping Haiti. Despite their obvious potential as a financing vehicle, the actual issuance of diaspora bonds, however, remains limited to a few countries for a number of reasons. First, there is limited awareness about diaspora bonds and many governments are usually deterred by the complexities of bond instruments. Second, many countries still have little data on the capabilities and resources of their respective diaspora. Finally, countries with political insecurity and weak institutional capacity would find it hard to market diaspora bonds unless credit enhancements are provided by more creditworthy institutions. In the end, while patriotism would motivate the Caribbean diaspora to provide funding at discounted rates, they must be confident that the funds would be used prudently. |

UWI International Conference on

Thursday 2nd June

Friday 3rd June

Saturday 4th June

Registration Fee: TT$600. |