|

|

|

|

May 2012 |

In academia the term “blue-sky research” is often used when the importance or relevance of the research findings is not immediately apparent, obvious or applicable to present day problems. Some academics argue that a certain percentage of this type of research should be encouraged or allowed while others vigorously oppose this type of “scientific adventure” because of the cost and also the perceived idiosyncratic or esoteric nature of these studies.

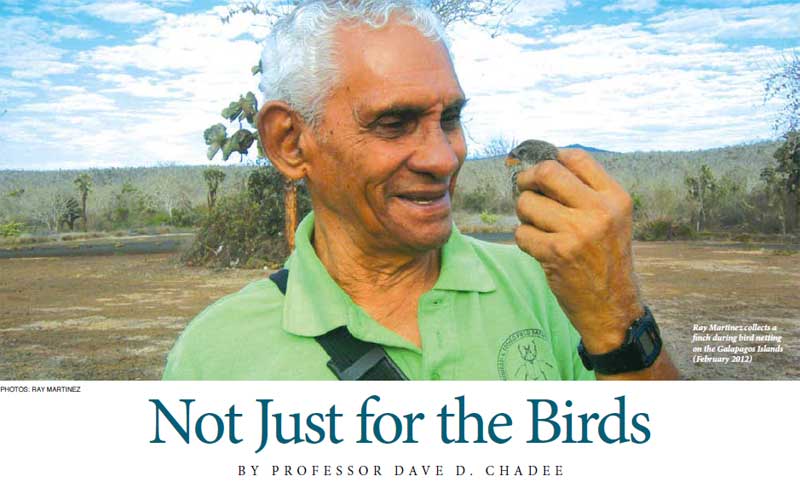

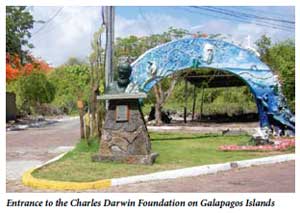

In January 2012, research assistant, Raymond Martinez, and I were invited to a workshop in the Galapagos Islands to help develop an action plan to control the invasive parasite Philornis downsi (originally described from Trinidad in 1968), which is attacking 17 species of birds in the Galapagos Islands. The workshop was funded in part by the Galapagos Conservancy and hosted by the Galapagos National Park Service and the Charles Darwin Foundation. It was reported that the Galapagos bird populations are under serious threat of extinction as a result of infections with Philornis flies which are causing very high mortality among nestlings, including the world famous Darwin finches and the very rare Mangrove Finches, the Floreana Mockingbird and the Medium Tree Finch. Sometimes there is 100% mortality of fledglings in a nest from these parasites. Those that do survive often have deformed beaks, are shorter in length, have reduced growth rates, anemia and poor fitness potential.

Current research in Trinidad is being conducted in collaboration with the International Atomic Energy Agency who provided research funds to Prof. John Agard, Head of the Department of Life Sciences and me, to develop rearing facilities in the Department of Life Sciences, UWI, St. Augustine, Trinidad. In Trinidad, Philornis downsi flies have been found in the nests of Smooth-billed Ani (Crotophaga sp.), Rufus-tailed Jacamar (Galbula sp.), Tropical Kingbird (Tyrannus sp.), Piratie Flycatcher (Legatus sp.), Great Kiskadee (Pitangus sp.), Grey-breasted Martin (Progne sp.), Southern House Wren (Troglodytes sp.), Tropical Mockingbird (Mimus sp.), Bare-eyed Thrush(Turdus sp.), Cocoa Trush (Turdus sp.), Bananaquit (Coereba sp.), Yellow-rumped Cacique (Cacicus sp.), Shiny Cowbird (Molothrus sp.), Palm Tanager (Thraupis sp.), Silver-beak Tanager (Ramphocelus sp. ) and White-lined Tanager (Tachyphonus sp.) bird species. Clearly, the work done 64 years ago by Aitken and Downs remains relevant and is being used as the “launching pad” to build strategies for the control of this major parasite of Galapagos island birds, with Trinidad being one of the major focal points to find natural enemies for biological control and for studies on parasite-bird interaction and association. Professor Dave Chadee is a Professor of Environmental Health in the Department of Life Sciences, at The UWI. |

For example, during the course of bleeding nestling birds for arboviruses in Trinidad in the 1950s, Dr. T.H.G. Aitken and Prof. W. G. Downs found that nestling birds were frequently found to be parasitized with many immature fly larvae. The flies were collected and specimens were sent to Dr. Rodney Dodge from Washington State University who subsequently revised the Insect Genus Philornis and described 10 species of invasive flies from Trinidad, eight of which were new species to science. This pioneering work by Dr. Aitken and Prof. Downs from the UWI’s Trinidad Regional Virus Laboratory during the 1950s to the 1960s was published in 1958 and remained unused outside academia for more than 60 years.

For example, during the course of bleeding nestling birds for arboviruses in Trinidad in the 1950s, Dr. T.H.G. Aitken and Prof. W. G. Downs found that nestling birds were frequently found to be parasitized with many immature fly larvae. The flies were collected and specimens were sent to Dr. Rodney Dodge from Washington State University who subsequently revised the Insect Genus Philornis and described 10 species of invasive flies from Trinidad, eight of which were new species to science. This pioneering work by Dr. Aitken and Prof. Downs from the UWI’s Trinidad Regional Virus Laboratory during the 1950s to the 1960s was published in 1958 and remained unused outside academia for more than 60 years.  The workshop provided an opportunity to share information, to identify gaps in the knowledge of the parasite, Philnoris downsi, and to discuss numerous control strategies, including traps with attractants, sterile insect techniques and biological control.

The workshop provided an opportunity to share information, to identify gaps in the knowledge of the parasite, Philnoris downsi, and to discuss numerous control strategies, including traps with attractants, sterile insect techniques and biological control.