Two men of the Caribbean; born here, but suckled in an England that offered a bitter teat for them to cut their teeth. The six years that separate them is not a lot, but it simply evaporates as they recount their early lives.

Listening first to Linton Kwesi Johnson, then Caryl Phillips at their respective one-on-one sessions at the April NGC Bocas Lit Fest was illuminating for what they revealed about the conditions that shaped them.

LKJ, born in Jamaica in 1952, went to live in England with his mother in 1963. Phillips, born in St Kitts in 1958, went to live in England with his parents when he was just four months old.

LKJ studied Sociology at Goldsmiths College at the University of London. Now a renowned dub poet, at 18, he had joined the Black Panther movement, working with Rasta Love, a collection of poets and percussionists. He has performed and lectured all over the world.

Phillips, an extraordinarily prolific author—fiction, non-fiction, drama, essays, columns, screenplays—practically every form, studied English Literature at Oxford University, and has taught all over the world.

On a day named Friday, they were brought together by the forces of literature; their stories of diaspora consciousness riveting, but full of the echoes that must be a dread beat in every migrant’s chest.

LKJ landed up in a London where the expectations of migrant families did not run particularly high. It was a place where they hoped to earn enough of a living to eventually return to their Caribbean homes. LKJ landed up in a London where the expectations of migrant families did not run particularly high. It was a place where they hoped to earn enough of a living to eventually return to their Caribbean homes.

“Our parents’ generation went to England with this kind of attitude that we’re gonna work for a few years then go back to the Caribbean. For the second generation it was clear to us that we were here to stay,” he said.

He soon discovered that the British expectation was also the same¬—that they would leave, and that they could eke out an income if they could, but should not aspire to moving up the ranks.

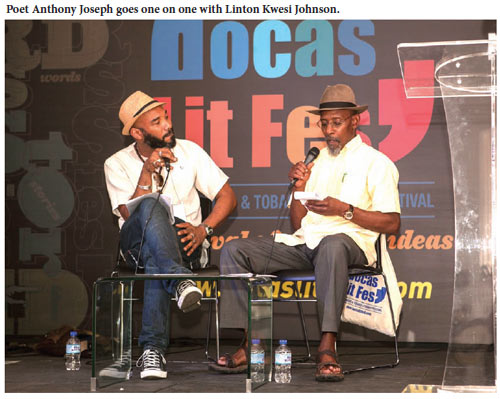

At the end of his one-on-one with Anthony Joseph, a questioner relates how a career advisor had told her she should aspire to being a manager at Marks & Spencer rather than a doctor. It ignites a memory.

“I was the generation before yours, but I had the same experience. I remember—I went to a comprehensive school and you had a streaming system—three tiers. And all, nearly all the black boys from the Caribbean were in the bottom stream. One or two were in the middle stream and very rarely you might find one in the top stream. You had to work your way up and I worked my way up from the bottom to the middle. And I remember when I was about 14, going to the careers master, and he said, What would you like to do Johnson, when you leave school? I said, Well sir, I’d like to become an accountant. He said, accountant? A big, strong lad like you… an accountant? He said, We need lads like you in the force.”

It was the kind of thing that was a common feature in what Phillips described as “an upbringing of daily marginalization.” So by the time LKJ hit 18, and encountered the work of W.E.B. Du Bois, he was ripe for revolution.

“I discovered black literature as a member of the Black Panther movement, because going to school in England, there was nothing in the school curriculum that gave you the slightest indication that black people wrote books—so it was like a revelation to me.”

It made him want to articulate how his generation felt growing up in England in a racially hostile environment, and poetry gave him a voice—a voice he said it took him 20 years to find.

In the meantime, Phillips was hearing Linton’s revolutionary beat. He had been two thirds though his English degree before he read a book by a black writer. He was in the US in 1978 when he realized “people who looked like me could write books.”

“When I was leaving university at the end of the seventies, it was a very contentious time to be black in Britain. It was the emergence of a second generation, whose concerns and frustrations and anxieties with Britain were being powerfully articulated by Linton, and a generation of writers was emerging who were the children of West Indian migrants and because I went to university—certain things were expected of me. … I hesitate to use the word, but I think it is applicable, I was expected to be compliant, to be grateful in a sense, for having been touched on the forehead by the establishment.”

“And I blame Linton! I wasn’t grateful. I was anything but grateful. I was angry and frustrated and as annoyed as any of the rest of my generation.” He was now, “beginning to step out of the ivory tower, which is universities everywhere that were enclosed, protected spaces, into the world to try to find out who I was in a society that was not seeing me for who I thought I was. I thought I was much more complicated and I had a richer history than that which was offered to me as a mirror by the British society.”

Growing up in white, working class Yorkshire, Phillips felt an instinctive kinship with other diasporan groups and their shared “fight for visibility.” The concept of home was troubling.

He went to St Kitts; hoping to acquaint himself with the kind of landscape described by George Lamming; to know what mangoes and pawpaw and jack fruit trees looked like; to behold the flower of the jacaranda, looking for a more reflective mirror, if not a home.

“Home is the most difficult word in the English language I think for diaspora people, which after all, apart from the Amerindian population, we are all diaspora people in the Caribbean. We have to stitch together where we are from ancestrally—be it India, or Africa, or Syria or England, wherever it might be—with the reality of life here. So the word home is a contested word in the Caribbean. Growing up in England that was the word that caused me the most problems in the house, because my parents would talk about home and it didn’t mean anything to me, but I knew it meant a helluva lot to them. But then again this was a place I’d never seen and there was no indication they’d ever be able to take me to see it.”

“Daily I was reminded that Britain didn’t consider me a person who should sit down on the sofa and make themselves at home.”

But even as Britain offered house, but not home and hearth, it was there, in the formation of communities of ‘outsiders’ that a different sense of belonging was fostered.

For LKJ it was a powerful bond that transcended physical space. For LKJ it was a powerful bond that transcended physical space.

“One of the great things about being part of the diaspora is that you develop a Caribbean consciousness which is not so easily available to you if you are living in the Caribbean. I mean there is no Caribbean consciousness as far as I am concerned outside of cricket, never mind Caricom and this sort of thing…. But when you live in England, we all become part of the same community,” he said.

And just as it has provided Phillips with magisterial imperviousness—he told his interviewer, Margaret Busby, that he never reads anything people write about him—it has given LKJ an ease in his skin that is nothing short of mellow.

“I am not into this schizophrenic consciousness, double-vision consciousness kind of thing. I am quite comfortable being called a Black British poet. I am equally comfortable being called a Caribbean poet. …I don’t see any contradiction between the two.”

Times have changed since the seventies, LKJ acknowledges, and much of his life’s work has been dedicated to bringing about those changes.

“We were on the periphery. When I was a youth growing up in England, black people were marginalized. We were treated like third class citizens. We had to wage struggles. We had to organize ourselves, form political organizations, resorted to riots, insurrections and rebellions in order to integrate ourselves into British society. This [mainstream] is where we’re reached through those struggles.”

It stirred him, remembering how his accountant’s ambitions had been dismissed.

“That’s why I wrote this poem, Inglan is a bitch—because my parents’ generation—they were constrained in the way they could fight racial oppression because they had responsibility.

“That first generation built a solid foundation for us you know. John La Rose called them the heroic generation because of what they were able to achieve in spite of the racial hostilities.

“My generation now, we were the second generation. We were the rebel generation because we refused to tolerate the things our parents reluctantly tolerated, and we didn’t have the same fetters. We didn’t have the same responsibilities. We didn’t have the same considerations; and it was through our rebellion that we began to change Britain… and we changed ourselves in the process.”

The 2014 NGC Bocas Lit Fest featured a number of firsts this year, with activities taking place in both Trinidad and Tobago; among them a day of readings held at the St. Augustine campus of UWI, which is one of its supporters. For more on the Festival, please visit their website at http://www.bocaslitfest.com/

|