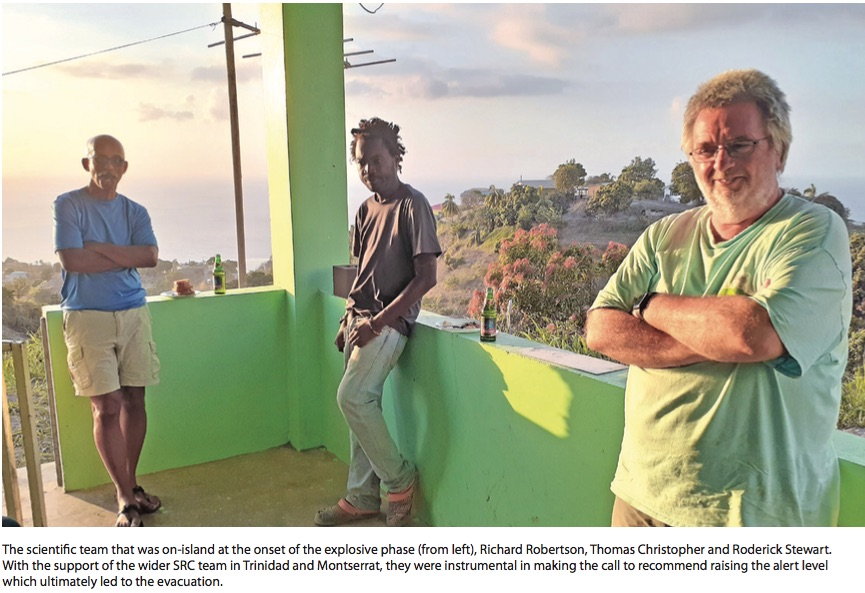

It may sound strange, but when the La Soufrière volcano erupted on April 9 in St Vincent and the Grenadines, geology professor Richard Robertson dressed for the occasion. His somber suit consisted of a black t-shirt with the text “La Soufrière” on the front and matching black pants. Robertson had been based at the Belmont Observatory on the island – approximately nine kilometres away from the volcano – starting his first rotation on December 31, 2020, where he led The UWI Seismic Research Centre’s (SRC) scientific team as they monitored volcanic activity and prepared for the inevitable explosive eruption.

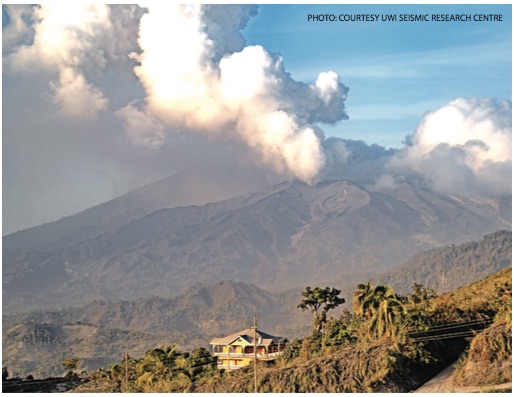

When the mushroom cloud finally shot over eight kilometres high into the air, Robertson, with his fellow team members volcano-seismologist Roderick Stewart and volcanologist Thomas Christopher, was calm in the midst of chaos, satisfied by the fact that their forecasts helped the government make crucial decisions, including evacuation of the red and orange zones (communities surrounding the volcano) on the night of April 8.

“The first event in the morning (on April 9) wasn’t too surprising,” said Robertson. “There was a lot of excitement. Nothing beats seeing [the volcano] rise. It looks alive and there’s a lot of adrenaline. As a scientist, I’m always interested in seeing it, but it’s a good and a bad feeling because I know there’ll be a lot of damage. Seeing it and understanding it are two different things though, and we had to compartmentalise in order to continue doing what was needed under the extreme stress.”

As expected, the eruption caused widespread devastation. Approximately 20,000 people were evacuated – many of whom remain in shelters. The ensuing ash fall damaged, and in some cases, completely destroyed, public and private properties such as homes, hospitals and schools. The water supply system was disrupted. Crops were decimated in a country with an economy based largely on agriculture. The United Nations has since deemed the event a humanitarian crisis.

The eruption destroyed one and cut power to three of eight seismic stations installed by SRC, which had to be quickly replaced, and as fieldwork continued, Robertson witnessed firsthand the aftermath of the eruption.

“Our masks weren’t just for COVID at that point. The ash was caked on the streets and you had to walk and drive slowly because everything gets kicked up into the air when you move. There’s a constant smell of burning and the grit gets into your eyes and blurs your vision. It’s really not pleasant,” Robertson recounted.

While in the field, he saw trees collapse and roofs cave in under the weight of ash, which he described as a heavy “grey snow”. At the observatory, Robertson and team had to continue working in between constantly sweeping ash away from the floor and equipment. They even had to worry about ash getting into their food.

This was not his first experience with La Soufrière, however. Robertson, who is Vincentian, was a teenager when the volcano last erupted 42 years ago in 1979. The strong earthquakes and tremors leading up to the eruption were familiar. This time, however, he was in a position to help:

“I became a volcanologist because of the ‘79 eruption. One of the reasons fundamentally that I did this is because when Soufrière erupted back then, I did not see people who looked like me or spoke like me, who were giving advice to the government, apart from Dr (Keith) Rowley. The thing that was impressed upon me the most was the fact that we had a volcano that could erupt again in the future and there was nobody in St Vincent that could understand what was happening. And that is what I set out to do. It’s terrible to see what the volcano can do in terms of damage, but if it does, at least I can help.”

And help he did. The SRC first detected effusive eruptions at La Soufrière on December 27, 2020 from their headquarters in St Augustine. In the effusive phase, molten rock or magma pushes to the surface and gently oozes out, producing lava flows and lava domes. By December 29, they confirmed that there were high temperatures caused by the magma reaching the surface and the team was deployed to the island on December 31. They got straight to work installing seismic monitoring stations, ground deformation sites and a camera at the summit to increase the accuracy of information collection.

The Belmont Observatory had to be quickly renovated in order to be habitable. The seismic stations enhanced monitoring of the growth and development of the volcano’s dome. Additional monitoring techniques were also used, which included drone flights and mapping. In mid-March, activity began to change with the occurrence of volcanic tectonic earthquakes (VTEs) – high-frequency vibrations caused by rock fracture or minor fault movement associated with deformation. According to Robertson, the VTEs were the first cause for concern.

There was another period of VTEs on April 5, but they went into tremors on April 8, which led continued up to the explosions the following day. They started discreetly on April 9 but went into near continuous explosions later that day up until midday on April 11, when the gaps between explosions increased from about 1.5 to 8 hours.

The eruptions from April 9 to 11 were much larger than 1979, and data is still being collected on how much so. SRC scientists have described the eruption as unusually intense, which they say is not necessarily related to climate change, but the configuration of the dome.

SRC director Dr Erouscilla Joseph said the increased monitoring, coordination of field and monitoring activities, outreach and advising, completed with limited resources, is a feat of which both The UWI and SRC can be proud. Joseph noted that SRC responsibilities entailed much more than simply communicating data. There was a lot of coordination involved with multiple organisations, which was made more difficult because of the pandemic.

The SRC worked with multiple agencies including the National Emergency Management Organisation, Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA) and the Office of the Prime Minister. They also had to create a social media programme and participate in virtual and public town hall meetings in St Vincent.

Joseph noted that the SRC’s contribution to saving lives was as important as the scientific monitoring: “We approach this as scientists, but it’s a risky job and we continue to do it because we’re conscious that people’s lives and livelihoods could be affected. This is why we’re careful with monitoring volcanic activity. It may be of scientific interest, but the human aspect is one of the big things we strive to keep in mind.”

Even though the SRC is under-resourced, said Joseph, they have received a grant to assist with replacing equipment and the continued work in St Vincent from the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility, financial assistance from CDEMA and other donor agencies, and donations of equipment from the US Geological Survey's Volcano Disaster Assistance Programme (USGS VDAP) and energy services company Halliburton.

Although the intense volcanic activity has decreased, heavy rainfall has caused mudflows (lahars) from the ash build up. Landslides and floods are delaying the clean-up efforts and exacerbating damages. Robertson noted that living in shelters poses many challenges and empathised with those still there. An ending or return to normalcy is unclear. He said he’d even heard of people returning to check on their homes to find items stolen.

“There’s a lot of concern about life and livelihood. Some people have gone back to try to save their homes by cleaning up and so on, but the mudflows are going to continue to destroy. Most people I’ve spoken to just want to know when it will be safe to return. Hopefully that will happen soon,” said Robertson.