Some things are just meant to be. You feel the tug of possibility, and if you’re brave enough, you take the leap of faith and fulfil your destiny. So it was for Carmelita Bissessarsingh as she set out on a journey she didn’t know she was taking, one that led her to owning two of Trinidad and Tobago’s cherished gingerbread houses and preserving a history that would otherwise have been kept behind their closed doors.

The Angelo Bissessarsingh Heritage House, formerly The Meyler House, and The Boscoe Holder House were built over 100 years ago by famed Scottish architect, George Brown. That they were landmarks along Carmelita’s path is fitting. An artist and recent graduate of UWI’s Department of Creative and Festival Arts (DCFA), with a degree in Visual Arts and a specialisation in design, she always held a fascination for colonial-style houses. Her chosen thesis topic? Climate Change and Colonial Architecture.

“These old houses were able to stand the test of time,” she says. Their “material choices [and] architectural designs… worked for our environment.”

Today, we complain about the increasing heat and aggressive rain. Yet “these houses were built... to not have these issues,” and she wonders, “Why did it change to what we are existing in now, a box with little windows and air-condition?”

So, when she had an opportunity to view The Meyler House in Belmont last year – she and her aunt, UWI’s Professor Ann Marie Bissessar (an imminent scholar and teacher of political science), were in search of a new home – she instantly knew it was hers. Walking through the wooden house, with its elaborate fretwork, high ceilings and 14-foot doorways, one can understand why.

“I didn’t have to see the inside to make up my mind... It was just ‘yes!’”

Professor Bissessar simply asked, “What you want to do?”

Carmelita put in an offer. “I was really, really happy.”

Living history was made when passion met foresight, and inspired by her late brother, beloved local historian, Angelo Bissessarsingh, she said to her aunt, “We can’t live in a house like this. We have to share it.”

That’s what Angelo was about, she says. “The mere fact that he started a virtual museum for free, giving out that knowledge, helping people research, tracing [their heritages].. It’s about making sure that things are preserved and continued for everybody else to enjoy.”

She named the house after him “because he represents preservation. He represents history. It was a joy for him.”

And so, in December 2022, Carmelita opened The Angelo Bissessarsingh Heritage House with the support of her aunt; her father, Rudolph; and brother and co-owner, Mario.

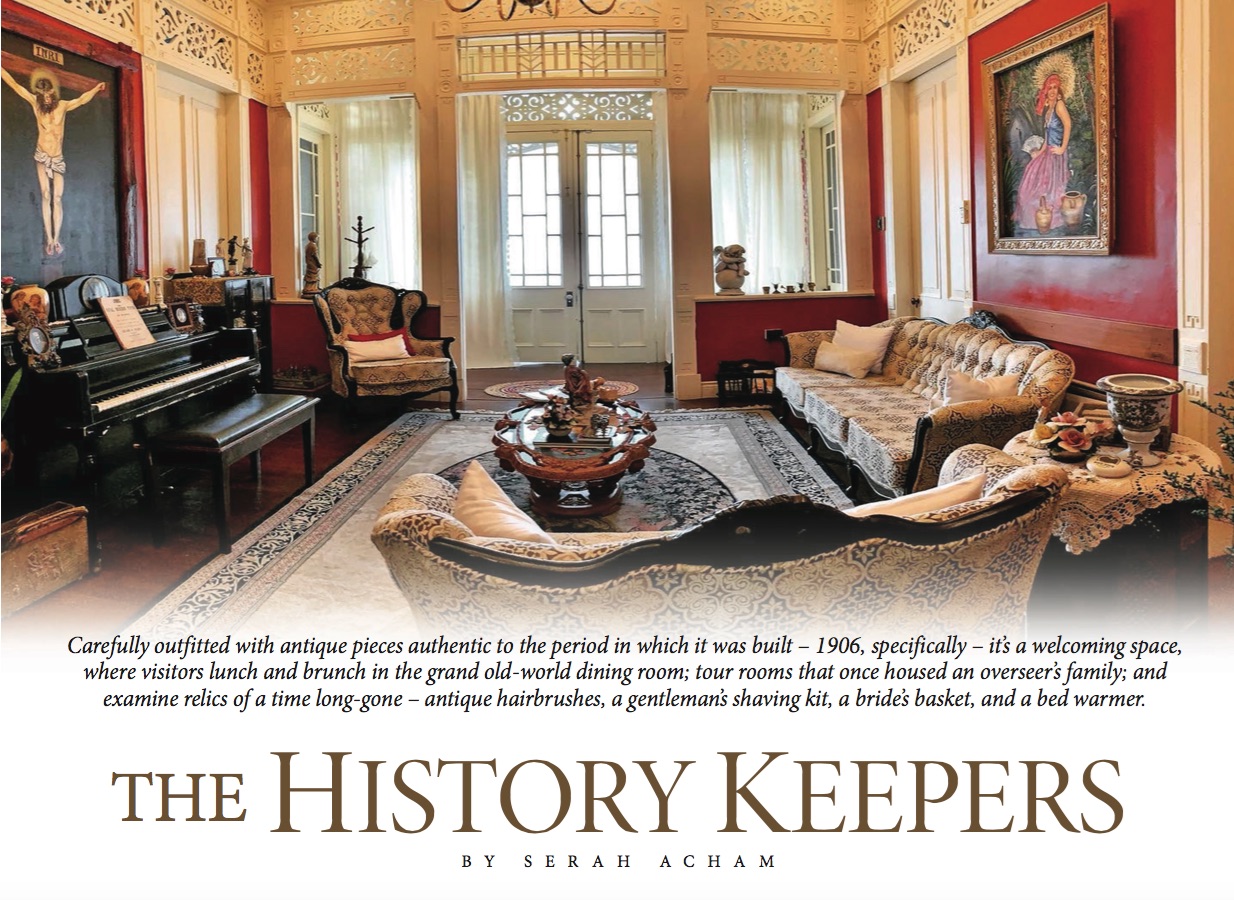

Carefully outfitted with antique pieces authentic to the period in which it was built – 1906, specifically – it’s a welcoming space, where visitors lunch and brunch in the grand old-world dining room; tour rooms that once housed an overseer’s family; and examine relics of a time long-gone – antique hairbrushes, a gentleman’s shaving kit, a bride’s basket, a bed warmer.

The small library, filled with books and other items from Angelo’s historical treasure trove, is a wonder all its own. A World War I helmet hangs behind the door, along with his impressive collection of swords. A cannon ball sits at the foot of an old secretary’s desk, and on top is what looks like a stone shard that, Professor Bissessar informs me, is from the year 600 BC.

As I am perched upon an antique damask-covered loveseat in a sitting room lit by an elaborate chandelier, my eyes zero in on pieces that remind me of things I’ve seen in my own family’s homes. The Persian rug under my feet looks like the one my grandmother once had in her living room. The vintage figurines and little houses are like those still on the shelves of the homes I grew up in.

This, Professor Bissessar tells me, is not by accident. In furnishing the house, they put in hours of research to ensure that each piece is historically accurate.

Carmelita adds that when visitors marvel at ornaments resembling things their mothers and grandmothers once owned, they knew they were relevant to the time.

Observing the thought and care put into composing this house, one would think these women spent a lot of time acquiring these items after the house was bought and its future planned. Not so. About two years prior to her purchase, before having any inkling of the jewel that awaited them, Carmelita was hit by her first bout of insight, this one unconscious, and she began a collection of her own.

“Two, three years before we bought the house we were like, ‘we want to hit up some garage sales and see what [they] have’,” she recalls.

She hit the jackpot. Among her spoils: two giant wooden pillars, huge doors and windows, a beaten-up couch set, and a piano.

“I thought, ‘this is awesome. I cannot believe it’... I just wanted [them].” Reflecting now, she says, “It just happened. I don’t know how to explain it.”

It turned out that, unbeknownst to anyone, her path was already set.

“I listen to myself and I think ‘nobody’s going to believe this’, but it really was very unplanned. If I planned it,” she acknowledges, “it wouldn’t be as perfect as it is.”

And still, we’ve not come to the end of the story. Having been denied the home she thought she would live in, Professor Bissessar said to Carmelita, “Camy” as she affectionately calls her, “you need to find [another] house for us to live [in].”

Carmelita knew The Boscoe Holder House, built in 1888, was on the market and, costly though it was, both women loved it. She made an offer – lower than the asking price, but, she thought, “why not?”

Fate already on her side, she got through. The owner, the late Mark Pereira, wanted her to have it.

“He wanted the artist,” Professor Bissessar explains, because the ‘law of ancient lights’ dictates that “once an artist resides in the house, you cannot put up skyscrapers. The artist has the right to light.”

“That house has never not had an artist in it,” Carmelita adds.

Good fortune not lost on these women, they have equally high ambitions for the Boscoe Holder House.

“The house will have one room for visiting artists, [and] I would love to do workshops there,” Professor Bissessar shares.

Right now, this niece and aunt wonder team are focused on their work at both houses. While they set up The Boscoe Holder House, they’re busy hosting tours, school visits and events at the Angelo Bissessarsingh Heritage House. They’re also preparing Angelo’s West Indian book collection to be housed there as a reference library for anyone who needs it.

“I believe it was meant to be shared,” Carmelita says of the Belmont house. She calls it a “time capsule”, and explains that few people today may ever experience a house like it.

Her fear, she says, is that part of history will be lost. And the thing she appreciates most about their endeavour is the “shared joy of seeing people come and interact”. On entering, some are hesitant – to sit on the couches, soil the carpet with their shoes, eat on the dishes – but Carmelita’s response is always “come in”.

“We’re more about experience. We want people to enjoy this house as much as possible because we enjoy it.” If Angelo were alive today, she says, “this house would be booming with people and he would have been extremely proud.”