|

November 2012

Issue Home >>

|

You wouldn’t knowingly give your child poisoned food, would you? Aren’t you concerned about the qua l i t y of the environment we will leave for our children? If you are, then greater attention must be paid to the manner in which our food is produced in the Caribbean. What quality of water and soils are we going to leave? Would there be any topsoil left for farming in the future? What about our indigenous species of crops and livestock?, These are some of the burning questions addressed in the book “Sustainable Food Production Practices in the Caribbean,” which was launched in early October.

The 458-page to me is like a splash of cold water in your face: it wakes you up immediately. Farmers in the region, especially local farmers are known for their injudicious use of synthetic pesticides to protect their crops from disease and insects, and their overuse of fertilisers.

“A lot of farmers over-apply fertilisers. They waste money and they contaminate the soil,” explained Dr. Wayne Ganpat, co-editor of the book, and a lecturer in the Department of Agricultural Extension at The UWI. Ganpat, who joined the Faculty of Agriculture three years ago, is a former Deputy Director of Extension Services in the Ministry of Agriculture, Trinidad and Tobago. \

Unfortunately, these particular chickens are coming home to roost in terrible places: there’s a high incidence of cancer among the farming community in Trinidad and their relatives, confirmed his co-editor, Dr Wendy-Ann Isaac, a lecturer in crop production.

Dr Isaac did her PhD thesis on the use of organic pesticides and fertilisers by Fair trade banana producers in St Vincent. “Consumers in the developed world are demanding that their food be safe to eat and produced in environmentally sound ways,” pointed out Dr Ganpat.

“If [Caribbean] consumers demand the same, then farmers would have to produce safer food.” As a result, extension officers in Ministries of Agriculture across the region would have to provide farmers with the technological knowledge to do so.

As it is, many of the extension officers are not adequately trained in sustainable techniques, and often only up to diploma level. The book is aimed primarily at extension officers and technicians, in the hope that once they have learned the practices they will pass on this information to farmers. It is also a valuable resource for students of agriculture.

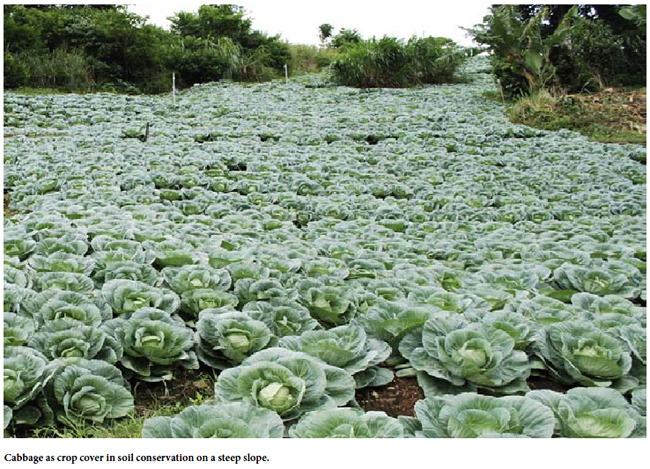

This is why the 20 chapters, authored mainly by lecturers and some graduate students from the Faculty of Food and Agriculture at UWI, as well as UTT lecturers, is written in an easy, accessible style with little technical jargon. It focuses on how to grow crops on hillsides, using contouring to reduce erosion and runoff; integrated pest, disease and weed management; how to integrate biological, chemical and cultural practices, and more.

The book opens its discourse with soils and soil management practices appropriate for the region. Much of the opening deals with farming on hillsides, since much of the land available for agriculture in the region – with the exception of Guyana, Jamaica, Belize, and Trinidad – is hilly and steep. The use of heavy machinery is not sustainable. Tilling the soil with heavy machinery has negative effects on the soil, including loss of nutrients, and the ability to store water. Tilling also results in a higher rate of runoff of fertilisers and chemicals. It reduces the amount of organic matter in the soil, such as microbes, carbon compounds, earthworms, ants and other beneficial inhabitants of the soil. “If we lose our topsoil,” said Dr Ganpat, “if we contaminate our soil and water, and we progressively decimate all our biodiversity, what will happen to us?”

The book covers livestock production with a focus on sustainable feeding practices. Marketing strategies, quality assurance practices and appropriate post-harvest production practices are also discussed.

Many of the practices are already being used in the Caribbean, but on a small scale. The authors consistently advocate crop and livestock production techniques that require an ecological approach, aimed at reducing the use of water, chemicals and pesticides and the preservation of the region’s soils, flora and fauna.

The book seeks to popularize methods that are already in use: for example, how to use garlic as a natural pesticide, how to establish contours and rubble drains; how to do a soil test as a first step to determine the amount of fertiliser needed and discusses leaf-nutrient analysis as an effective agricultural practice.

The Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA), a well-known joint international institution of the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries and the European Union, based in the Netherlands supported the book, and has ordered 500 copies to distribute in ACP countries. The UWI also provided financial support.

While some countries in the region, including T&T do have policies in place restricting and regulating the use of chemicals in agriculture, they are not strictly enforced. “We need more monitoring, more certification programmes,” said Dr Ganpat. Policies that regulate how food is produced needs to be revisited, he said. Instead of offering subsides on spraying equipment, which is associated with the use of synthetic pesticides, the Government should offer, for example increased subsidies for contouring and the use of safer pesticides,” he suggested.

It’s a hard job to convince farmers to change their ways, admitted Dr Ganpat. “This is why consumers need to demand that food is produced in an environmentally sustainable manner. This book is to prepare the food producers for the way forward,” he said. “The days of food production at any cost – those days are gone. We must be resolved to leave our environment in a better condition than it is at present. Our children deserve no less!”

Sustainable Food Production Practices in the Caribbean (Ian Randle Publishers, 2012) is now available at The UWI Bookshop and Keith Khan’s Books Etc. |