|

|

|

|

November 2015 |

Drama happens from the onset with the sounds of Madame Butterfly juxtaposed against a wide shot of Our Lady of Fatima atop the hills of Laventille. One of the most talked about aspects of the film – for better or worse – Laventille sprawls before the viewer in all her glory and the film demands that you take her in. In the Q&A session following the screening, Professor Mohammed noted that, “There was a moment when I went up the hill and I was sitting looking at Mary, and imagining the epic tragedy of Laventille…and nothing spoke to me the way Madame Butterfly does and the idea of starting with that was also engaging with that tragedy by representing a vision of their pathos.” To understand the tragedy of Laventille is to go to back to the beginning and reimagine how the “city that built the city” contributed to the creative, spiritual and architectural hallmarks we now identify as undeniably ‘Trini.’ The film does this by giving us an insider’s perspective through the eyes of its residents. Members of the Rada, Hindu, Christian and Orisha religious societies warmly invite the camera to “come in, come in” and be witness to a community united in faith. Observatory Street’s history is excavated as a reminder of the Laventille of yesteryear – the site where Don Cosmo Damien Churruca, Spanish Officer and scientific navigator, led an expedition to fix the longitudinal points in the New World relative to Cadiz, Spain in 1792 resulting in the establishment of an observatory at Fort Chacon. The placement of these historical gems throughout the film is no coincidence, since its inception was part of a three-pronged project made possible through The UWI Trinidad & Tobago Research and Development Impact Fund (RDI), Leveraging Built and Cultural Heritage of East Port of Spain, led by Dr. Asad Mohammed. The project also includes a 3-D model of the city and a book, which are mentioned in the film. When asked if being tied to such a specific message limited the scope of the film, Mooleedhar said, “They gave us the freedom to go in any direction we wanted – because of that awareness it helped mould the direction of the film – it was an opportunity.” With much creative freedom comes the responsibility of a dynamic personality to channel it, and Wendell Manwarren fills that slot as both an omniscient narrator and subject in the film. He provides the artistic vehicle to bring to life the Laventille depicted in great literary works by reciting quotes from Derek Walcott, Wayne Brown and Earl Lovelace – delivered with rooted oratorical flourish as only Manwarren, Belmont native can. For Manwarren, other artists, makers and Carnival enthusiasts alike, Laventille is remembered as their coveted muse, “She was the hill, she was their own. They would have fought for her, lifted her up, made her queen.” Laventille’s reciprocal affections however, lie not with her admirers, but the smallest among them – the children. The film closes with its most picturesque scene – an old-fashioned kite fight between two neighbourhood children, set to the pulsating score of a drum riddim section. One kite flies high above the other with Laventille’s hills as backdrop – whose kite will get cut first? The camera shifts back and forth as the kites become entangled and finally, the loser’s kite is guillotined; yet our gaze remains hopeful, watching the unattached kite flying freely, disappearing into the atmosphere. So is the future of Laventille, a city whose narrative is often etched with violence and tragedy, yet she guides her dwellers to look upwards, remembering that they are the light of the world, for a city built on a hill cannot be hid. Professor Patricia Mohammed is taking a break from filming to complete her next book. Michael Mooleedhar is working on the pre-production stages of the film, “Green Days by the River.”

Jeanette G. Awai is a freelance writer and marketing and communications assistant at the Marketing and Communications Office, UWI St. Augustine. |

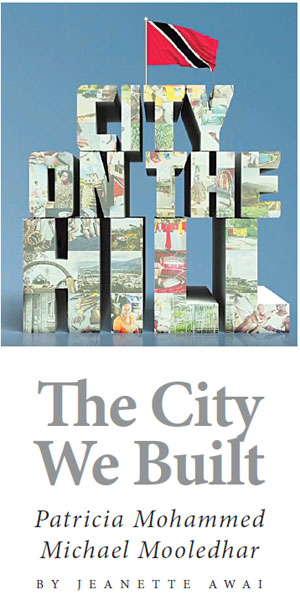

Big Ben. Time’s Square. Christ the Redeemer. These iconic images need no introduction and easily conjure sweeping landscape shots in our minds. Professor Patricia Mohammed and UWI Film Programme alum Michael Mooleedhar allow East Port of Spain audiences to see themselves on screen alongside these iconic landmarks, as co-directors of the documentary, “City on the Hill.”

Big Ben. Time’s Square. Christ the Redeemer. These iconic images need no introduction and easily conjure sweeping landscape shots in our minds. Professor Patricia Mohammed and UWI Film Programme alum Michael Mooleedhar allow East Port of Spain audiences to see themselves on screen alongside these iconic landmarks, as co-directors of the documentary, “City on the Hill.”