|

|

|

|

September-October 2010

|

A son of the soilBy Professor Nazeer Ahmad By 1949, the College was already established as the premier centre in the world for teaching and research in tropical agriculture. Its library was also recognised as the most comprehensive on the subject anywhere. There were commodity research programmes for crops such as cocoa, cotton, sugar cane, and bananas, and important advances were also being made in areas such as plant propagation and storage and processing of plant products. The academic programme was also well established by that time and it consisted of three components. One was a three-year undergraduate diploma programme (DICTA), and two postgraduate programmes: a one-year Diploma in Tropical Agriculture (DTA) started in 1948, and the other, normally a two-year associate programme (AICTA). This course was inaugurated from the inception of the College. The AICTA was recognised as the most prestigious qualification in Tropical Agriculture at the time and graduates from many countries were enrolled. The selection process for admission to this course was rigorous, particularly for graduates of the College itself, since these graduates did not have to apply for admission, but rather, if you were considered admissible, you were invited by the Principal to enroll for the course. Very few graduates from the College, who were mostly West Indians, received such an invitation, having failed to meet the required academic standard. The undergraduate agriculture programme was really high quality professional training carried out by qualified and experienced staff, some of whom were world authorities in their fields. Over three years, it progressed from pure sciences to applied sciences impacting on agriculture, then to agricultural sciences in the final year. Practical work at all stages was emphasised, with hands-on experience in all important operations. For instance, during my studentship, the present University Field Station was acquired and developed. It was formerly a bamboo plantation where an international publishing company was experimenting in the use of bamboo for making paper. In the development of that site, we had practical experience in clearing bamboo with a bulldozer, fencing the lands and making the first roads. We also had the experience of land preparation: sowing, harvesting and processing the first crops grown on it. During the second year of the course, each student had to maintain five plots with different crops. The plots were located where the Faculty of Engineering now stands. The now weedy pond in the quadrangle of the Faculty was our irrigation pond. It collected waste water from the entire campus, including the swimming pool, which was merely a small “cement pond” where the present pool is now located.

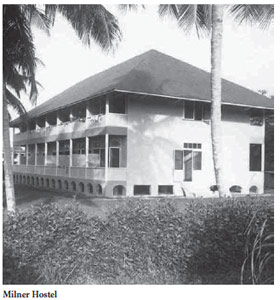

The undergraduate course was essentially residential since students at various stages had to begin their day at 6am. Exceptionally, permission was given to live off-campus, but the accommodation had to be approved and located in the St Augustine area. From 1922, when the first students were admitted, to 1950, no female students were enrolled at the College. In 1950, four were admitted for the first time, two undergraduates and two in the DTA programme. During my studentship also, there was significant physical expansion of the College. The Sir Frank Stockdale and the Sir Francis Watts (Soils) Buildings were constructed and commissioned. The College celebrated its Silver Jubilee in 1951, when these buildings were commissioned. Milner Hall was also extended with the construction of the North and South Blocks. There was significant social life on the Campus, even though the academic programme was so intense. Participation in sports was encouraged and facilitated. Students were invited to visit staff members and their families socially in the evenings at their homes in a kind of “open house,” when we had the chance to see our lecturers from a different perspective. Since the staff lived on the College property, these visits were convenient and usually pleasant. Although numbers were small, the student body was very international in composition and to live and work with students from all these countries and cultural backgrounds was itself an enriching experience. When I returned to the Campus as staff in 1961, I recall how surprised I was at the extent of the physical deterioration of the facilities. This was because of the However, as we know, this situation changed at the take-over. The Faculty of Engineering was added and Agriculture was incorporated as a Faculty with no additional building space. Arts and Sciences came later. These other disciplines were added with little additional resources and I recall the serious differences of opinion at the time among staff members at the advisability of expanding into these new areas under the existing economic conditions and the likely consequence of lowering academic standards. Some members of the largely expatriate staff even resigned their positions in protest. Student numbers increased slowly at the beginning of The UWI, with only Agriculture and Engineering being offered, but with the addition of Arts and Sciences this changed. The student body comprised a high percentage of more mature students than at present, and I believe there was also a closer connection between the students and the university administration. One of the consequences of the rapid expansion of the University in more recent times is the slow but steady decline of Agriculture as an academic discipline. It was undoubtedly the solid academic foundation upon which the campus was built, but now it is not even a Faculty on its own. In this regard, I vividly remember a remark made by one of our most distinguished agriculture graduates at an international conference in Port of Spain recently, when he said that Agriculture at St Augustine is disappearing. We can hope that the discipline will not actually disappear, and Agriculture will again experience better times if one of the important regional goals is food security and if the University is to regain its pre-eminent status in this field.

|

When I came to the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture as an undergraduate student in 1949, the campus consisted of the original Administration Building, the Principal’s House (now the Principal’s Office), and a building which had been constructed as a hospital (Yaws Hospital) located at the present car park east of the Bookshop. This building housed the Department of Agriculture, Botany and Plant Pathology and Entomology, classrooms and teaching laboratories. South of this building was the Chemistry and Soil Science Building, now known incorrectly as the CFNI Building. The original building of Milner Hall existed at its present location with a student dining hall and common room located approximately where Daaga Auditorium is today. All the lands now occupied by the sports complex [SPEC], Canada Hall, the Library, Arts and Social Sciences, the car park, Engineering, Land Surveying, CARIRI, Natural Sciences and Chemistry were experimental farms for the College (ICTA). The cemetery is where it is today. The College Campus as such, was complete with the cricket field as it is today, and the rest of the grounds was used as a golf course.

When I came to the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture as an undergraduate student in 1949, the campus consisted of the original Administration Building, the Principal’s House (now the Principal’s Office), and a building which had been constructed as a hospital (Yaws Hospital) located at the present car park east of the Bookshop. This building housed the Department of Agriculture, Botany and Plant Pathology and Entomology, classrooms and teaching laboratories. South of this building was the Chemistry and Soil Science Building, now known incorrectly as the CFNI Building. The original building of Milner Hall existed at its present location with a student dining hall and common room located approximately where Daaga Auditorium is today. All the lands now occupied by the sports complex [SPEC], Canada Hall, the Library, Arts and Social Sciences, the car park, Engineering, Land Surveying, CARIRI, Natural Sciences and Chemistry were experimental farms for the College (ICTA). The cemetery is where it is today. The College Campus as such, was complete with the cricket field as it is today, and the rest of the grounds was used as a golf course. The academic standards established by the College were very high. There was no accommodation for failing any courses since there were no supplemental examinations or repeats. Students were actually allowed to fail in one subject in any year, but this subject could not be Agriculture, Botany or Chemistry. Once a student was deemed unsuccessful, he had to leave and we were saddened to see some of our colleagues go as the course progressed. The rate of failures was always high. In my year for instance, we started with 20 students, but eight graduated. Our year had the largest number of admissions at the college. One of the course requirements of this rigorous academic system was that the classes were very small. If my graduation group consisted of eight students, the one before had only four! Clearly, with such small numbers of students, we had individual and personal attention from the lecturers and this was a great learning privilege, especially in laboratory classes. Since there were no demonstrators or tutors, our lecturers performed these functions and were in attendance throughout practical classes.

The academic standards established by the College were very high. There was no accommodation for failing any courses since there were no supplemental examinations or repeats. Students were actually allowed to fail in one subject in any year, but this subject could not be Agriculture, Botany or Chemistry. Once a student was deemed unsuccessful, he had to leave and we were saddened to see some of our colleagues go as the course progressed. The rate of failures was always high. In my year for instance, we started with 20 students, but eight graduated. Our year had the largest number of admissions at the college. One of the course requirements of this rigorous academic system was that the classes were very small. If my graduation group consisted of eight students, the one before had only four! Clearly, with such small numbers of students, we had individual and personal attention from the lecturers and this was a great learning privilege, especially in laboratory classes. Since there were no demonstrators or tutors, our lecturers performed these functions and were in attendance throughout practical classes.  reduction of financial support for ICTA by the British Government during the period of negotiations with UCWI for the transfer of the College. I then fully understood a statement I heard from Sir Arthur Lewis, Principal at UCWI, at a lecture he gave at the Town Hall in Georgetown, Guyana in 1958, when he said that ICTA was almost too good a gift to UCWI, which simply did not then have the resources to take over, maintain and improve the facilities.

reduction of financial support for ICTA by the British Government during the period of negotiations with UCWI for the transfer of the College. I then fully understood a statement I heard from Sir Arthur Lewis, Principal at UCWI, at a lecture he gave at the Town Hall in Georgetown, Guyana in 1958, when he said that ICTA was almost too good a gift to UCWI, which simply did not then have the resources to take over, maintain and improve the facilities.