|

|

|

|

September-October 2010

|

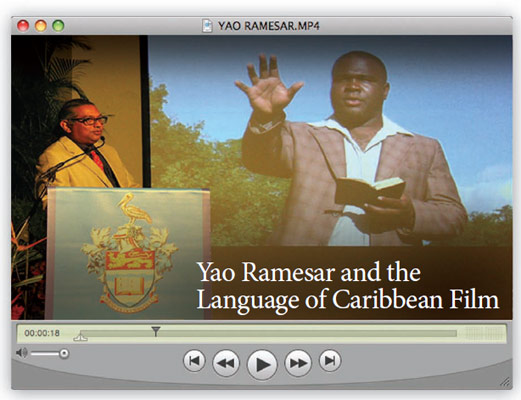

“Hollywood,” said Yao Ramesar dismissively, “is a small town in L.A,” but yet, it is taken as the producer of all that is quintessentially American cinema. This, and other factoids, formed the central themes of Ramesar’s Public Lecture at UWI’s LRC, on September 13. It was the first event in a partnership between the University of the West Indies and the Anthony N Sabga Caribbean Awards for Excellence. We, the narrative consuming world, according to Ramesar, seem to be trapped in Hollywood’s conception of “linear narrative and romanticism”, and more recently, Bollywood’s equally narcoleptic escapist themes. These preoccupations lead to neglect, if not a degeneration, of indigenous identity and self-understanding. Ramesar placed the blame not only on environmental but human factors, noting that the country that had produced the only new musical instrument of the twentieth century had fallen to eighty-fourth place (out of 139) in global competitiveness and fifty-fifth place in global innovativeness. He was also critical of attempts by the Trinidad & Tobago Film Company, and governments past and present, to establish the country as a location for international films, which meant conventional Hollywood action films, at the expense of other genres. “There is a conception that art films are not commercial. But the most successful Trinidadian action film made $60,000 at the box office over months in Trinidad,” he said. “Abroad, one screening of one of my films makes $120,000.” Likening his films to unconventional Latin American and Caribbean writers, he said “People [abroad] read Wilson Harris and Garbriel Garcia Marquez and call it ‘magical realism’ but they don’t understand that here, it’s everyday life.” And that life is becoming increasingly chaotic because it is lived, but not recorded, or commented upon. The post-independence period in the Caribbean, he reminded the audience of about 300 people, produced an enormous amount of literature and artistic work directed at things as they were in that period in the Caribbean. But the present generation “seems to have lost that urge”. They are not making use of the medium of the times: film. “Both Naipaul and Walcott have said if they could do it over again, they would write for the movies,” he said. Ramesar used clips from his films and a generous sampling from his Sista God, the only Trinidadian film to be selected for the Toronto Film Festival. He spoke of the use of existing landscape and architecture, people and natural light. For example, scenes from Sista God were shot in a bar called “Desert Storm” in Pasea Road, Tunapuna, owned by an American soldier who had been a combatant in the first Desert Storm. One of the actors in the film was a former American Marine, who now lived here, and who appeared in his authentic uniform. Another portion of the film was shot in the slum community of Bangladesh, and used a woman from the area as the central character (in that part of the film). Ramesar is a UWI Lecturer in its Film Studies programme, and was the inaugural laureate in the Anthony N Sabga Awards in 2006. His fellow laureates were Monsignor Gregory Ramkissoon (who was this year awarded the Order of Jamaica), and Prof Terrence Forrester. The lecture was prefaced by remarks from UWI Principal Prof Clem Sankat, who expressed satisfaction at the partnership between UWI, and the ANSA Caribbean Awards. Awards Programme Director, Maria Superville-Neilson also remarked that the partnership was “desirable and natural” since three of the ten laureates were UWI academics and lecturers (Ramesar lectures at UWI, and the other two are Profs Kathleen Coard and Terrence Forrester of Mona). It is expected that more lectures featuring Caribbean Awards laureates in partnership with UWI are expected. Photogrpahy by Aneel Karim |