|

|

|

|

September 2013

|

“Federation start. People began flowing out of their houses, alleys and lanes like peas spilling across a linoleum floor. The whole neighbourhood swarmed the mule cart with their bowls, plastic cups and cooking tots, and one woman, who could not find any utensil large enough to carry away the flour, resorted to using her ‘po,’ her bedpan, having first washed it out under the warm afternoon water of the public standpipe. “The men and women knew about germs and mules and the public road and public decency, so they scraped off only the good flour from the top. They swept the black flour into the gutter, and washed the road with water from the public standpipe. “The mule-cart driver then washed his face and continued on his journey. He understood the villagers. Flour was the staple of their diet, but during those starving war-days there was none, and the people had been ‘cutting and contriving’.” Sobers, who has a BA in Visual Arts and describes herself as “UWI furniture” chose to do her MPhil in researching the environment and coping mechanisms of families whom she’d become acquainted with through her husband. She started off with ten families, but for one reason or the other (in one case, the main link committed a murder and went to jail) the number decreased to six. In real terms, what she has done for over three years is to virtually embed herself with these six different families from various parts of the island, not just observing them, but partaking in what was to her a radically different way of living and of seeing the world.

So when Candice opted to do this degree programme, she titled her thesis rather technically and almost as a mask of the raw nature of her research: The Aesthetics of the Mundane: Techniques of Resourcefulness and Survival Among Working Class Trinidadians. The practice-based thesis is being accompanied by paintings, drawings and a handbook, “Threads of Survival: Sixty Resourceful Technique for Family Life,” as part of a series of that would represent the body of her work for the MPhil. She had the handbook printed at her own expense, and planned to sell copies at her art exhibition which ran for a week in mid-September at the Art Society Gallery. The exhibition too is part of the MPhil submission. The paintings and drawings on display were done during the course of her time spent with the people she’d begun calling by the academic term, “informants” but who are now remembered in a much more human way. She has many stories to tell: some sad, some scary and discouraging, but at the same time, many display the capacity of the human mind to adapt and adjust to all manner of situations. And in the stoic, accepting way they have of coping with all the bottles and big stones life keeps throwing at them, there are remarkable examples of how different people’s realities can be, and how what can be normal for one person, is utter disaster for another. In the process of this programme, which she officially started in 2010, having already established contact with the families, she too had to make many adjustments, becoming pregnant and then caring for a newborn while traipsing up and down from Couva, Macoya, Curepe, Santa Cruz and in Sangre Grande, down in a valley, a place so beautiful they call it Avatar. I ask about the composition of the families, and she describes one household. In there are the grandparents and their four children—two girls, two boys—and their partners; one of the girls has what she refers to as a “visiting union” as the father of her one child does not live there. Her siblings altogether have another six children, ages ranging from three to seven. That’s 16, sharing two bedrooms, and though all of them hold menial, low-paying jobs, except for the grandmother, things only hold together because of the things they do “by the side.”

Do they live harmoniously? “They have their fights, some awful fights, but it worked more or less because they are not all at home at the same time. So the management of the space works because they have different shifts and sometimes somebody sleeps by a friend and then comes down, because it’ really too much if they were to sleep altogether in that house.” She was introduced to scams undertaken as routinely as a day’s work—like pretending to be car park attendants when there are fetes and charging $20 to ‘watch’ the cars. She heard about burglary and robbery techniques. Gambling, drinking, and drug use were constant factors, thought at varying degrees from family to family. And she formed friendships that have persisted, particularly one with an elderly coke addict. When the grandfather, whom she calls that particular family’s “main informant,” died, she realized a lot of her information was lost. He had shown her how to make concoctions like shampoos from Bois Canot and cocoa, and many other home remedies for ailments. She began to collect data for these techniques and recorded them, even as she was learning to incorporate them into her own lifestyle. Like a treatment for fever. “But then there is a fever technique that they showed me, with a burning plate, and when you use that, one night, it’s gone, and it’s not even something to take internally. It’s just something from the outside. So I thought these things were just priceless,” she said.

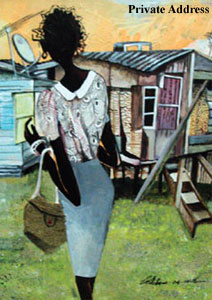

“What I noticed too that came out of the informal education was a level of pride in what was being done. So it’s not just necessarily making ends meet, but it became a product that was something that was different, and it’s not marketable, but extremely tasty, like sometimes the food. So one family made a pepper sauce called Bunass but when they explained to me how they made it, it’s not like a regular pepper sauce, they could use it in anything, you know? And I couldn’t eat it because it was too hot. “But most times they have stories behind these things, and it is their grandparents that may have told them about it, and they made little changes to it to make it better for them, and I realised that this is very rich. So I didn’t want to sell their ideas, because it wasn’t right. So what I did was create the book out of it and ask permission.” As she tells stories of her encounters and revelations, it is clear that this has been a life-changing experience for her. The art that resulted from her sojourn reflects it. The pieces depicting houses, cluttered kitchens, outdoor bathrooms and even a sexily clad woman making a detour to avoid people seeing where she lived—these pieces distort colours, lines, proportion, juxtapositions—pretty much the way artists do. But hovering at the edge of her words and images, there is something that says that the concept of what is normal, like art, has many different interpretations; even in the way we cut and contrive. For more information on Candice Sobers’ work, please visit her blog at http://candicesobers.blogspot.com/ or email her at candycanefield@hotmail.com |

In his 1999 food memoir based on growing up in Barbados, “Pig Tails ’n Breadfruit” Austin Clarke relates what happened when a mule-cart driver transporting bags of flour had a mishap. One of his cart’s wheels hit a big rock on the road and it catapulted him, the mule, the cart and the bags of flour onto the road; one of them split wide open.

In his 1999 food memoir based on growing up in Barbados, “Pig Tails ’n Breadfruit” Austin Clarke relates what happened when a mule-cart driver transporting bags of flour had a mishap. One of his cart’s wheels hit a big rock on the road and it catapulted him, the mule, the cart and the bags of flour onto the road; one of them split wide open. The word research usually constructs images of laboratories or libraries; either way, it suggests something structured, solitary and, well… serious. In academic circles, it must meet rigid standards, and sometimes it is tough for researchers to get past the rigidity with which those standards are defined. Academic documents are a fine example of how unrelenting the language alone can be when it comes to making communication obscure.

The word research usually constructs images of laboratories or libraries; either way, it suggests something structured, solitary and, well… serious. In academic circles, it must meet rigid standards, and sometimes it is tough for researchers to get past the rigidity with which those standards are defined. Academic documents are a fine example of how unrelenting the language alone can be when it comes to making communication obscure. “The mother isn’t working, the grandmother isn’t working, but everybody else is working—but it’s really low-end jobs: working in the mall, selling clothes for [a popular mall store] working in the malls, working for CEPEP, somebody works in a bakery…”

“The mother isn’t working, the grandmother isn’t working, but everybody else is working—but it’s really low-end jobs: working in the mall, selling clothes for [a popular mall store] working in the malls, working for CEPEP, somebody works in a bakery…” It was also clear to her that having these homespun remedies and recipes brought a sense of value to the families; each one acting like a badge of honour.

It was also clear to her that having these homespun remedies and recipes brought a sense of value to the families; each one acting like a badge of honour.