|

September 2018

Issue Home >>

|

Dr. Anjani Ganase, marine scientist and coral reef specialist, reports on the Latin America and Caribbean Congress for Conservation Biology (LACCCB) Conference. This inaugural conference was hosted by the Department of Life Sciences at the St. Augustine campus, 15 years after the Latin America and the Caribbean section of the Society for Conservation Biology was formed. She concludes that scientists in every ecosystem must connect, collaborate and conserve before we lose not just species, but our home.

The theme of the LACCCB conference was “Rainforest to Reef: Strengthening Conservation Connections Between the Caribbean and the Americas.” Most natural spaces – montane ecosystems, forests, rivers, savannahs, mangroves, and shallow marine and deep-sea environments – were represented. But these forced consideration of the “unnatural” spaces, including urban areas, roadways and agricultural lands. It is hard to disconnect discussions of conservation biology from the impact of our species: humans. Most discussions focused on protecting organisms and their habitats through ecological strategies – building connectivity, restoration and repatriation, and social change – effected through education, policy and regional collaboration among one species, us.

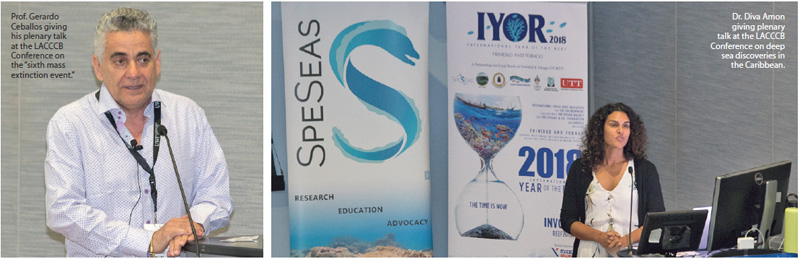

First came the bad news. This was delivered by Gerardo Ceballos, Professor of Environmental Science at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico in the opening plenary. Prof. Ceballos presented the global overview on the status of biodiversity among vertebrates.

There was evidence of significant loss in the global biodiversity over the last 100 years, significant enough to be considered “the ongoing sixth mass extinction event.” The main drivers of these extinctions are growing human populations and their consequential actions – resource extraction, loss and alteration of habitats, pollution, disease and introductions of invasive species. Extinction rates calculated from the declining populations of mammals, birds, fish and amphibians species (to name a few) are expected to continue into the future, especially with the long-term impacts of man-made climate change. However, there is still a chance to alter the trajectory through persistent and even creative conservation strategies but we need to act with urgency. Prof. Ceballos established the first challenge of the conference – creative thinking for conservation strategies.

Later conference talks definitely provided specific regional cases for Prof. Ceballos’ theory. Studies about disturbances to habitat and animal populations, as well as conservation efforts have been undertaken all over the Latin American and Caribbean region. An example of creative thinking was conveyed in the plenary talk of Dr. Howard Nelson from the University of Chester. Dr. Nelson discussed the benefits of tapping into the valuable asset of regional (ecological, social and political) diversity in the Caribbean and South American region: utilising indigenous strategies, he proposed, may improve biodiversity management of protected and unprotected areas. Such strategies offer innovative approaches for conservation management of unprotected natural areas or privately owned lands. What were his take home messages? Collaborate and build connections across borders, language barriers and cultures. Having a broad diverse scope of understanding at multiple scales (from community to national and regional levels), and even outside the realms of traditional ecology, will only improve our conservation efforts. With that, he delivered the second challenge – engagement across languages and across social structures, as far as the national agenda.

And so we kicked off the series of formal talks and workshops with creativity and engagement in mind, with doubles and roti mixed in. Throughout the varied habitats, common themes of human disturbance – including invasive species and pollution – pervaded most ecosystems. But there were also success stories about habitat restoration and repatriation as well as social engagement. Discussion about habitat fragmentation and the methods to improve connectivity across habitats and ecosystems, as well as the challenges to assess spatial distributions on broad landscape scales – even across borders or with the sea between – resonate with me as a marine scientist. I have experienced similar challenges in coral reefs and coastal ecosystems. These discussions provided insight and opportunity for adapting innovative ideas and technologies to different ecosystems – at the levels of the rainforest or the reef.

To end the conference, it was refreshing to be taken on a journey of discovery, delivering hope. The third plenary speaker, Dr. Diva Amon, deep-sea biologist fellow at the Natural History Museum in London, spoke about the discoveries in the deep ocean of the Caribbean and Atlantic. In the deep Caribbean, new invertebrates are still being identified signalling greater diversity among marine organisms. We appreciated this simple reminder of the reasons we became scientists and conservationists: the joy of exploration and discovery. Despite the new discoveries, she stressed that even these remote ecosystems were not immune to human activities; she expressed urgency for others to get involved and expand the research efforts. Losing deep-sea ecosystems to commercial activities such as drilling even before we even get the chance to understand them would be a tragedy. Dr. Amon’s challenge: discover and protect what’s there before we lose it.

There were about 150 attendees to the inaugural conference, coming from 17 countries within and beyond the Latin American and Caribbean region. Over the two days, over 150 organisms and groups of organisms were discussed: plants, mammals, amphibians, fresh and saltwater species and even bacteria. Roughly 100 study locations were mentioned in the Latin American and Caribbean region, but with special mentions of Antarctica, Sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian Ocean. These locations covered more than 20 different types of ecosystems from the high altitude montane ecosystems and cloud forests to the deep-sea mounts of the Caribbean as well as the urban and agricultural landscape.

We were taken around the world to devise strategies to protect home, whether we consider home these two islands, or the planet.

|