SUNDAY 9 SEPTEMBER, 2018 – UWI TODAY

3

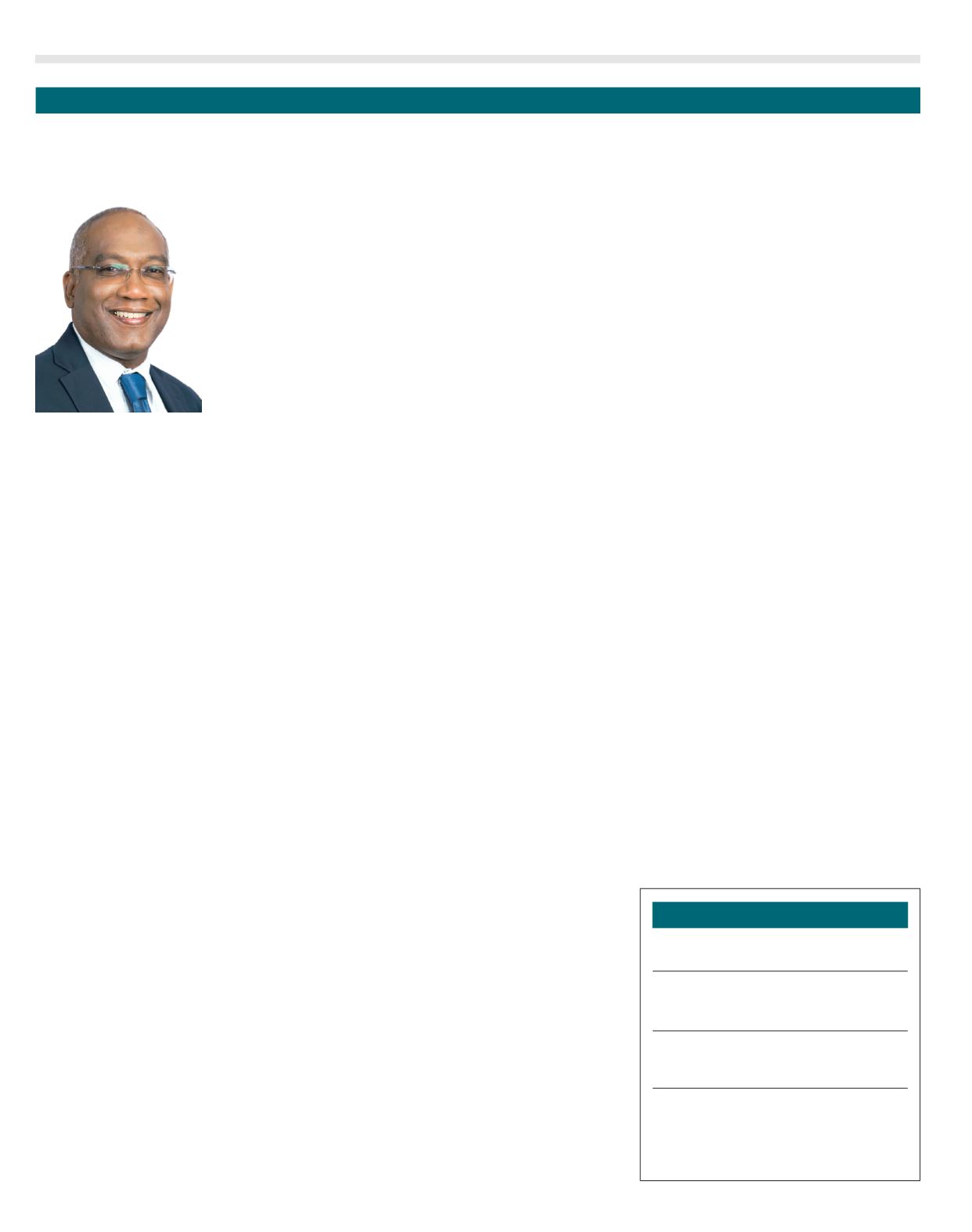

FROM THE PRINCIPAL

EDITORIAL TEAM

CAMPUS PRINCIPAL

Professor Brian Copeland

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING

AND COMMUNICATIONS

Dr Dawn-Marie De Four-Gill

EDITOR

Vaneisa Baksh

email:

CONTACT US

The UWI Marketing and

Communications Office

Tel: (868) 662-2002, exts. 82013 / 83997

or email:

A s a n a t i o n ,

Tr i n i d a d a nd

Tobago has just

marked 56 years

of independence.

In compar i s on

with many self-

d e t e r m i n e d

nat i ons of t he

world, it is, as the

song says, young

and moving on.

No one wou l d

deny the fact that in many ways we are still inching

our way towards a national identity.

Regionally, a failed attempt at forming a

Federation of Caribbean territories set us off on the

path towards independence from colonial rule in

the two decades following 1962, when Jamaica and

Trinidad and Tobago gained their independence.

That time and that movement defined an epoch

in West Indian development. Indeed, it was in

1962 that The UWI of today took its form with the

establishment of the St Augustine and Cave Hill

Campuses to expand the University College of the

West Indies formed in 1948. Globally, the world

itself was going through revolutionary changes

that would transform world culture, politics and

geography – the Civil Rights movement in the

US which had strong links with the growth of

black awareness and the black power movement

in Trinidad and Tobago, the Cuban missile crisis

and the threat of nuclear warfare, the hippie youth

movement, the space race and the first manned

trip to the moon. In those days, particularly in

the sixties, a sense of idealism and excitement

permeated the region, as visions of the kind of

societies we could build seemed ready to take off

once the colonial mantles were shaken off.

In the post-independence world, however,

many of those dreams seem to have been buried. It

has not turned out quite the way it was imagined.

On the economic front, for example, a March 2018

World Bank Brief reported that in Jamaica “over

the last 30 years real per capita GDP increased at an

average of just one percent per year, making Jamaica

one of the slowest growing developing countries

in the world.” The 2018 CDB outlook for the

Caribbean projects a 1.8% economic growth, still

behind the 3% global projections. Similar economic

challenges across the Caribbean, our vulnerability

to climate change effects exacerbated in part from

environmental abuses, the social malaise of income

inequality and increasing crime rates and concerns

about food sustainability continue to be our greatest

challenges.

There is almost a sense that the region is

operating in neutral, without a clear idea of what

should be done to deliver on the promises rendered

at independence. It is tempting to focus on the

many negative challenges to society and to give up

on the Caribbean as failed states. However, as I said,

we are still quite young as nations go. It is up to us

who populate and govern these territories that make

up the Caribbean to strategically plan, set clear

targets for sustainable growth and development and

then agree on clear action plans to achieve that state

within reasonable time. This would require a vision

for development, strong resolve and courage from

our leaders and many sacrifices on the part of the

ordinary citizen.

Can this be done? Do we as Caribbean peoples

have what it takes to sacrifice traditional practices

and biases to do whatever is necessary to forge

a society that betters the one dreamed of by our

forefathers? Others have. The most commonly

referenced example is Singapore whose economy in

1962 was well behind that of Trinidad and Tobago

and Jamaica, but whose visionary leader, Lee Kuan

Yew, worked hard to impose a strong culture of

detailed planning, intolerance to corruption and

cultural transformation to make it one of the

strongest economies in the world with a GDP of

around USD500 billion, reported as the 3rd largest

per capita. Lee Kuan Yew’s policies were not without

opposition but givenwhere this country came from,

I suspect that only a few Singaporeans would trade,

what many see as a harsh legislative regime, for the

level of prosperity they have achieved.

At the risk of prolonging this thread of thought,

I must make reference to very recent discussions I

held with colleagues on South Korea and Norway.

In 1997 South Korea was facing bankruptcy

and took a US$ 58-billion loan from the IMF

under onerous contingencies. One picket sign by a

displaced worker said it all – “I.M.F. = I’M Fired.”

However, within three short years the country

turned around its economic fortunes and proceeded

to pay back the loan. Underscoring the success

was prudent planning and the sacrifice made by

the South Korean peoples who willingly bought

into the notion of “burden-sharing” and in a clear

demonstration of national pride and patriotism

donated their personal treasured gold belongings

– family heirlooms, rings, medals, trophies and

the like – to be melted down into ingots for

international sale.

I have always admired howNorway has invested

its oil and gas revenues into a Sovereign Fund, on

which the Trinidad and Tobago Heritage Fund is

modelled in part, to take care of future generations.

It is now the largest such fund in the world, sitting

at some USD 1 trillion in 2018. The Norwegians

have crafted a “fiscal rule” that governs how the

fund is used to phase oil and gas revenues into the

immediate economy while ensuring that the fund

capital remains and grows. The Fund is also guided

by an Ethics Council that blacklists investments in

companies associated with severe human rights

violations, gross environmental degradation and

corruption.

Finally, closer to home is the Central American

Republic of Costa Rica which, despite its current

challenges and the fact that it abolished its army

some 70 years ago, has a very stable democratic

government and has fairly successfully diversified

its economy from agriculture. The country has

clearly set its eyes on achieving the UNdevelopment

goals for environmental sustainability. It was

identified by the New Economics Foundation as the

greenest country in the world and plans to become

carbon neutral by 2021. Indeed, by 2016 98% of

the country’s energy from “green” sources, notably

hydro-electric, geothermal, solar and biomass.

To varying extents, these global examples reflect

the importance of having a commitment by all

national stakeholders – Government, the business

sector, NGOs and the ordinary citizen - to the

shaping and execution of detailed and well thought

out national development plans. But this will all

be for naught if the populace is not adequately

motivated to comply. Can we, for example, work

together to improve our food security through

better collaboration between researchers and the

food sector to improve the viability of locally

produced food and through a deliberate action

by our citizens to change their buying habits from

local imports? After a generation or more of craving

Do we as Caribbean

peoples have what it takes

to sacrifice traditional

practices and biases to do

whatever is necessary to

forge a society that betters

the one dreamed of by our

forefathers? Others have.

AVision for Development

Continued on

Page 4