We were, after all, in the middle of a war. There was a base right here in Chaguaramas bustling with American soldiers and half the local population trying to find work there. Trying to unravel the mysteries of the movie-theatre accents, chewing gum and cigarettes. The Americans were also busy building roads and acquiring a taste for local wonders like rum, warmth and, um, nocturnal hospitality. Will anyone ever be able to explain why, in all of literature, every time you hear about American bases, chewing gum plays such an important role? We were, after all, in the middle of a war. There was a base right here in Chaguaramas bustling with American soldiers and half the local population trying to find work there. Trying to unravel the mysteries of the movie-theatre accents, chewing gum and cigarettes. The Americans were also busy building roads and acquiring a taste for local wonders like rum, warmth and, um, nocturnal hospitality. Will anyone ever be able to explain why, in all of literature, every time you hear about American bases, chewing gum plays such an important role?

In the year…never mind the year, this is exactly what my professor feared when he sent me in search of newspaper clippings about forgotten fiction writers of Trinidad from the 1940s. What he meant was that I was not to neglect my search for stories, poems and others clues about the local literary scene in that decade. What he said was: “Don’t read about the war.”

I read about the war. Because it’s just not possible to stick to one thing when you can have all the things.

On the second floor of the Alma Jordan Library, West Indiana has a world-unto-itself air. It is inhabited by dissertations, rare books, special collections and reference materials too important or fragile to be left to the dangers of the general, grubby-pawed public. The people who use it are as likely to be students as visiting scholars or independent researchers.

Dr Glenroy Taitt, head of West Indiana, would like to see more students coming across the border. See, the secret club aura is not real. In my undergrad days it pleased me to think of it as private space. I wanted to stay in that cold (it was always cold), walled-off, closed-door section of the big rambling building and let the careful hands of the librarians set the books I asked for in front of me. Never more than three at a time. This was no dream world but it was the world I dreamt of: West Indian studies wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling. It mattered not one whit what I was actually meant to be researching, there was always a reason to find a West Indian connection or reference.

Ask not what you can do for West Indiana but definitely ask what it can do for you

Dr Taitt has in his care the Special Collections of the St. Augustine Campus. The papers of Eric Williams are here. So too those of Sam Selvon – the author himself donated them to the university. Part of the CLR James collection is here. These are some of the better-known treasures. The names are famous and there’s an added layer of importance that comes from – in the case of these three in particular – being part of Unesco’s Memory of the World programme. There are less popular ones, less, arguably, significant ones. But that’s where the real alchemy that makes for the best research happens. Once the West Indiana and Special Collections folk agree to admit your body of work or papers into their realm, everything becomes important.

A giant corpus of legal material – estates, deeds, conveyances, small disputes – may seem dull even to law students. But to a historical novelist, it may be a brilliant source of quarry for a new work. With these legal papers a writer might bring from the past a story of ancestral fortunes, draw characters who may love or hate each other depending on the vagaries of inheritance, consider preferred china patterns of a household if it exists in an inventory of sale items. Imagine, this is by no means the most or even nearly the most extreme example of interdisciplinary work.

When most of us think of West Indiana, we think it is for students in Humanities or Social Sciences. Consider: it started all the way back when The UWI was the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture. Yes, you could say it started as a science library. All of this really does have something to do with crossing faculties for better research.

West Indiana and the discipline of thinking carefully about what I needed (remember, only three books at a time) and being very careful handling some fairly old type-written theses helped me to care about the work I was looking at and the people who kept it safe for me. Because these things felt precious I wanted to make the most of them, so I learned to take better notes and keep a sharp eye out for something that might help me later on or for a different reason from whatever the current one was.

Even during my war days I did not disparage the rest of the library. Far from it. Each floor had special nooks, tables or windows I spent time at. If I was thinking of Shakespeare I’d find a reason to be in the history section. Diaspora writing sent me to comparative religion and myth. And on a good day with not much to do I could take up residence in the sociology stacks to work on something truly important like poetry.

Get thee to a library

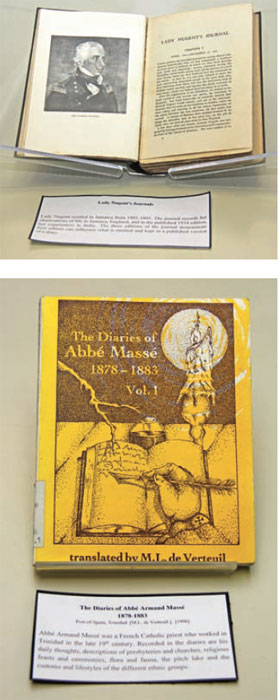

While West Indiana was never actually off limits to anyone, the process of accessing material if you were an undergrad required special permission. Those were the bad old days. Now, the division is open to all campus students and they are working on outreach programmes to encourage greater use of the resources. Once per semester an open lecture draws in academics from different backgrounds to discuss the different ways specific types of information can be used to enrich research. The most recent one, on the use of journals and diaries as source matter, was facilitated by historian Dr. Brinsley Samaroo and Dr. Nicol Albada from psychology. The session is very deliberately set up like this to demonstrate how students from varied disciplines can approach the same information and draw from it the facets relevant to them.

There’s also the Teaching with Special Collections programme. Here, faculty is encouraged to use West Indiana, but in particular focusing on the unique, the specially archived, original manuscripts and the like. Lecturers are encouraged to use this information to find new and engaging ways to teach. It’s important for this to reach the undergraduate part of the campus.

That keeps coming up, doesn’t it, this business of preaching to the first-degree seekers? So much of the work being undertaken by West Indiana and Special Collections is trying to make itself more accessible to the whole university and the wider public. The online catalogue of dissertations – the effort of digitizing as much as possible – can compete with far more resource-rich schools. The work is labour intensive and plentiful. But it has such noble goals: changing the perspective of the division as one that caters to graduate students and foreign academics; nor is it just for those reading arts or social sciences. All the work, all the programmes, are taking a hard look a student body long accustomed to getting by with their course books and a handful of references to pass their exams and term papers. And what they see is the need to increase the analytic skills of, well, everyone. The methodological acumen needs a boost. We need the ability to think beyond the easiest, most superficial way through the course outline.

The above, it’s not hype, and no, the library staff are not collectively running for guild positions. There are serious gaps and flaws in how we think about our education: the main one is a lack of stretch and creativity in how we conduct our research. Go talk to someone at the library about how to strengthen your work.

Anu Lakhan is a writer and editor. She still reads books made of paper.

|