|

|

|

|

April 2016 |

I have sought the permission of my hosts to focus on the three papers on the economy (specifically on the energy sector, leaving the very stimulating political discussions to others who are more qualified and more daring). Even so, I could not avoid making a passing comment on [Dylan] Kerrigan’s piece on the history of Woodbrook over the period 1920-1960. Now, I am not from Woodbrook (according to Kerrigan’s typology, I could not possibly have been part of the Woodbrook of that era). However, I attended Fatima College in the late 1950s and the early 1960s and I remember well what Woodbrook was then. And believe me, it was far from what is now – physically, culturally and in terms of its socio-political significance. In college, I remembered what it meant to be from Woodbrook. Kerrigan’s article demonstrated clearly the road through which Woodbrook travelled and left me to wonder about the origins and significance of more recent changes. I really hope that I could look forward to a sequel to this article. I thought that it was most appropriate that the first of the three articles about economics in this commemorative publication sought to give recognition to our first Caribbean Nobel Laureate and first West Indian Vice-Chancellor of our University, Sir Arthur Lewis. His contribution to economic policy-making in the Caribbean as well as to a general theory of economic development (if there is such a thing) was enormous though perhaps not sufficiently recognized. The article by [Ranita] Seecharan and [Roger] Hosein gives a concise but insightful review of Sir Arthur’s celebrated treatise on “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour,” and his development blueprint christened by Lloyd Best as “Industrialization by Invitation.” The blueprint was originally intended for the small economies of the Caribbean but, over time, was adopted by developing countries all over the world. Sir Arthur challenged the prevailing orthodoxy which insisted that the small economies of the Caribbean should focus exclusively on agriculture since they had no hope of achieving sustainable development through manufacturing activity. While there is much disagreement on elements of his framework even to this day, his proposed strategy of fiscal incentives, export promotion as against import substitution and the crucial role of Government intervention in the development process, became standard fare in the Caribbean and elsewhere. The notion that over time, the locals would learn the tricks of the trade and take over the manufacturing sector clearly did not envisage the capacity of multinational firms to protect their turf. In their article, Seecharan and Hosein see the Atlantic LNG project in Trinidad and Tobago, started in the late 1990s as a special case of Industrialization by Invitation. In my view that is somewhat of a stretch. While this project has clearly been an important part of Trinidad and Tobago’s strategy of gas-based development, to me it does not fit into Lewis’ IBI framework. The underlying assumption of the Lewis approach was that because the marginal productivity of labor and wages in the agricultural sector were low and that this gave the foreign investors easy access to a large pool of low-wage workers to be combined with their advanced technology to produce labor-intensive goods for export. Sir Arthur saw his strategy as a way of increasing employment opportunities for the excess agricultural labor force and at the same time, using the manufacturing sector as an agent of economic transformation. For all its success, Atlantic LNG has been essentially an extension of the mining sector, offering a negligible contribution to employment and limited value added. It came into being after the significant gas discoveries of the 1990s as a way of more fully exploiting our gas resources. Atlantic LNG was no more a product of “industrialization by invitation” than all the firms that made up the Point Lisas Complex. They all got fiscal incentives in varying degrees and they involved even greater value added. Atlantic LNG, for all its success, represented an increased dependence on our gas resources and could not have been seen as a tool of economic transformation. Arthur Lewis saw his manufacturing sector strategy as a way of transforming the economy. The paper notes the success of the Atlantic LNG plants gave a major boost to government revenues and foreign exchange earnings. This is certainly true. I was disappointed, however, in not finding some discussion of the questions and concerns that have plagued our gas-based strategy over the years. For example, several commentators have questioned our gas-utilisation plan, of which Atlantic is an integral part. About 80% of our gas production is converted into LNG to be exported. The conversion simply involves the liquification of gas to make it exportable, thus there is very limited value added. In fact the value added is transported from Trinidad and Tobago to the industrialized countries. Many people take the view that a better allocation of our exhaustible gas supplies between the export and the domestic market would have been more in our national interest. As total gas production has been on the decline, our petro-chemical industries have been starved for supplies. There is also a view that our energy taxation regime provides the wrong incentives. Traditionally oil was more heavily taxed than gas because gas was not considered as valuable. The disparity in the tax regime has continued even when gas prices rose sharply because the producing companies resisted changes in the gas regime. Moreover because Atlantic was perceived as a processing as opposed to an energy company it became subjected to a tax rate of 35% while oil companies are taxed at an effective rate of close to twice that level (about 67%). The point is that Atlantic may not be the golden goose that it is made out to be. Seecharan and Hosein did, in fact, recognize some of the limitations of Atlantic LNG’s performance and proposed that these be addressed through an active policy of Localized Economic Development based on greater Corporate Social Responsibility. Quoting from the concluding remarks of the article “Atlantic could certainly do more to assist its localized host community where the poverty rate is 24 per cent and the unemployment rate is 13 per cent”. I am not convinced that such an approach will yield the required quantum of resources or has much chance of succeeding, if only for the reason that the extractive industries operating in today’s environment see CSR as a marginal activity; a type of social service, not a strategy of local development. A similar recommendation is repeated in the article on Dutch Disease by [Roger] Hosein and [Rebecca] Gookol. The other two articles on the economy deal with the hot-button issues of Dutch Disease and Economic Diversification. The article by Hosein and Gookol gives an interesting new spin to the theory of Dutch Disease. While there are many definitions of the phenomenon, the term is most commonly used to refer to the negative consequences arising from large increases in a country’s national income. It is most commonly used in the context of commodity based economies and refers to a whole set of adverse factors, including for example: inflationary pressures in the non-commodity sector; these lead to a real appreciation of the country’s exchange rate which, in turn, retards the non-commodity export sector and promotes imports. The end result is that the non-resource industries are hurt by the wealth generated by the resource industries. The article introduces us to a different dimension of the Dutch Disease causality. It argues that Dutch Disease leads to a decline in genuine savings, defined to take into account the decline in commodity resource wealth as an offset to increased export revenues.\ According to the authors the causality works as follows: resource boom brings higher depletion rates along with higher export revenues. As commodity incomes rise there is the well-known tendency for an increase in consumption that can also negatively affect the nation’s savings. Lower savings could in turn also contribute to lower rates of human and physical capital formation. The line of argument has merit. Based on this analysis, to achieve inter-generational equity, the resource rents generated from exhaustible or non-renewable resources must be re-invested in reproducible capital. But the authors then apply this reasoning (called the Hartwick rule) seemingly to justify economic and social outcomes in Tobago. In my view this is another case of forced fit. First of all, the transfers from the Central Government, which comprise the bulk of the Tobago’s budgetary resources, are treated just as commodity export revenues. They are certainly not. Moreover from 2005 to 2013, a period in which there was a substantial increase in commodity export earnings, there was no commensurate increase in budgetary transfers to Tobago. Secondly, the calculations use several proxies because of the “unavailability of data.” The Central Statistical Office has produced inflation data for Tobago for many years. Yet the article uses the prices of agricultural commodities and construction materials as a proxy for inflation in Tobago. The Office of the Secretary of Finance produces annual GDP data for Tobago so it is not entirely correct to say that these data are unavailable. At any rate, it is not obvious that foreign tourist arrivals are a good proxy for economic activity in Tobago. There is a view that since the start-up of the new inter-island ferry service in 2008, the increase in domestic tourism may have more than compensated for the decline in foreign tourists. It is likely that ongoing oil and gas exploration off the Tobago coast, if successful, could create pressures associated with Dutch Disease. Thus the recommendations for increased investment in human and physical capital are in order. I do not think it is realistic to expect the oil companies to play a major role in the financing of these infrastructural investments, as a demonstration of corporate social responsible. (At least in this article the authors are somewhat less sanguine about the possibility.) I would suggest that an alternative approach, from a policy view-point, would be a government levy on the extractive industries with the funds earmarked for community development. The last of the articles on the economy is authored by three staff members of the World Bank and deals with our pressing challenge of economic diversification. For those who like to dabble in econometrics, the article contains a very interesting survey of a number of studies on the determinants of economic diversification in resource-rich countries. Not surprisingly the results are sometimes conflicting and counter-intuitive, underscoring the fact that there is no one blueprint for diversification. Instead diversification policies need to be tailored to the specific circumstances of each country.

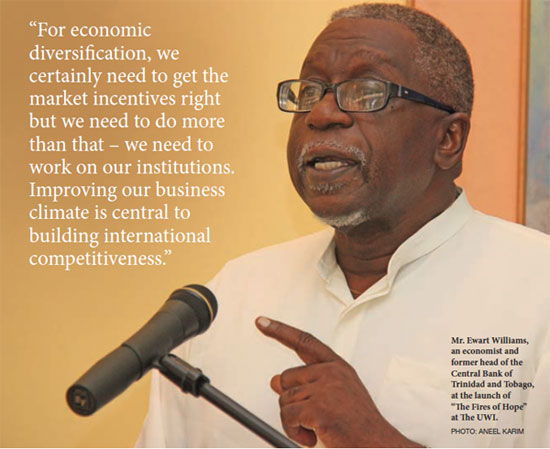

While the factors cited are indeed critically important, the article fails to adequately consider the role of our institutions in our still unsuccessful efforts at economic diversification. Recent research has begun to analyze the diversification challenge faced by resource-rich developing countries not solely in terms of economic incentives but through the lens of political economy. Thus, Alan Gelb from the Center of Global Development puts the blame squarely on weak institutions and poor governance. Gelb argues that “large natural resource rents make young democracies malfunction and there is tendency for these countries to lack accountability and to practice patronage politics.” According to Gelb, these small countries tend to become hostage to economic policies that are driven by short horizon, patronage-driven electoral competition and a non-transparent allocation of resource rents. Some of that may be operating here in Trinidad and Tobago, reflected in the disproportionate concentration of government expenditure on subsidies, transfers and make-work programmes, as against economic and social infrastructure. Our economy has serious skills gaps, particularly in the public sector, yet patronage politics tend to keep many competent managers and professionals from full participation, resulting in the under-utilization of scare human resources. This is a very informative and provocative article, which perhaps does not go far enough. For economic diversification, we certainly need to get the market incentives right but we need to do more than that – we need to work on our institutions. Improving our business climate is central to building international competitiveness. However, it is time that we accept that this requires not only reducing red-tape and improving our work ethic; it also means dealing with crime and corruption, which too, are major blots on our investment climate. “In the Fires of Hope” has certainly brought greater clarity to some of the economic and political challenges Trinidad and Tobago still faces 50 years after independence; and that is an important service. The three articles on the economy have all pointed to issues in the energy sector which have impeded progress towards economic diversification. The recent slump in oil and gas prices has made economic diversification even more urgent but a bankable diversification strategy is still not in the offing. I have tried to point out areas where the economic analysis and the policy prescriptions could be strengthened. Even with these shortcomings, “In the Fires of Hope” is a formidable undertaking and all those who made it possible should be commended. Mr. Ewart Williams, Chair of the Campus Council, was invited to critique the first of a two-volume series, dedicated to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Trinidad and Tobago’s Independence, “The Fires of Hope” at its launch on March 2, 2106 at The UWI. |

I must confess that even before reading the book, I was seduced by the catchy title “In the Fires of Hope” which conditioned me to expect as the dominant theme some kind of message that would reassure me that “things were going to be all right.” While the book did not quite provide that assurance, it certainly succeeded in fulfilling one of its aims – to add to the body of literature that illuminates our society’s understanding of itself.

I must confess that even before reading the book, I was seduced by the catchy title “In the Fires of Hope” which conditioned me to expect as the dominant theme some kind of message that would reassure me that “things were going to be all right.” While the book did not quite provide that assurance, it certainly succeeded in fulfilling one of its aims – to add to the body of literature that illuminates our society’s understanding of itself. Applying their econometric model to the specific case of Trinidad and Tobago, the authors conclude that the main impediments to economic diversification are the usual suspects: Dutch disease, largely brought on by counter-cyclical fiscal policies; the unsatisfactory quality of education; inadequate economic infrastructure; insufficient innovation and technological readiness outside the energy sector and a business climate still in need of improvement.

Applying their econometric model to the specific case of Trinidad and Tobago, the authors conclude that the main impediments to economic diversification are the usual suspects: Dutch disease, largely brought on by counter-cyclical fiscal policies; the unsatisfactory quality of education; inadequate economic infrastructure; insufficient innovation and technological readiness outside the energy sector and a business climate still in need of improvement.