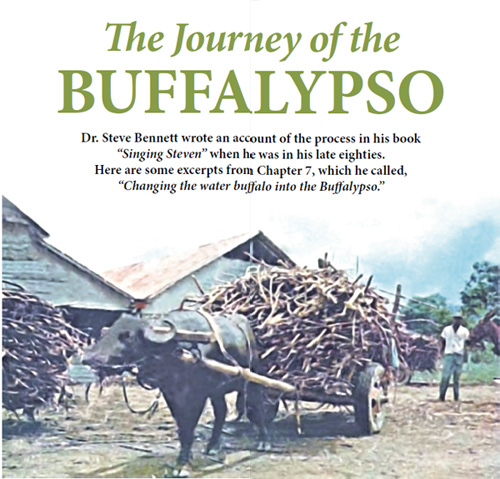

Dr. Steve Bennett wrote an account of the process in his book “Singing Steven” when he was in his late eighties. Dr. Steve Bennett wrote an account of the process in his book “Singing Steven” when he was in his late eighties.

Here are some excerpts from Chapter 7, which he called, “Changing the water buffalo into the Buffalypso.”

“There was a long-held assumption that water buffaloes were supposed to be resistant to diseases such as tuberculosis. When I did post-mortems on waterbuffaloes that had died, I found that contrary to unfounded beliefs, the water buffaloes did have tuberculosis. I decided to develop a TB eradication programme. I had done this type of work the year before I graduated from college. I worked for the State of Washington in the west coast of the United States. I was doing TB testing and also drawing blood for the control of Brucellosis. I did that job for three months so I was fully aware of what I was doing, and the benefits derived from doing it. When I tested the water buffalo herd for the first time I found that over 33% of the herd were infected with TB. This finding necessitated changes in procedures. I suggested that the pens in which these animals were kept had to have a concrete floor, and not a mud floor. Secondly, that all feed fed to the herd had to be off the ground [raised] and be fed in mangers or in “racks” and that clean water had to be available 24 hours a day, if there was going to be any hope to develop a TB-free herd. In other words, I could not slaughter 33% of the herd because the company needed these animals for pulling the carts during the harvest season. Disease control was imperative, but had to be pursued with common sense to be able to keep the operations ongoing. All animals, however, that were positive to TB, were put in one isolated pen and I started to test them every 6 months. The testing procedure was really a rodeo in itself. I had no facilities whatsoever. I needed to be innovative. I had to starve the infected buffaloes to be tested for two days. After the starving regimen, the herdsman would bring feed and put it in mangers for them to eat.

While they were eating I would have an assistant cleaning the tails off with alcohol, which I used as an antiseptic, and I would just come along and start injecting them with tuberculin for the TB test.

When I started to work at Caroni, no one knew anything about the management of large cattle herds and husbandry in general. I had to train whoever was working with me. It took me 10 years to eradicate TB from the water buffalo herd. I used the following policies – any animal that was positive for TB in the herd went to the abattoir or the slaughterhouse and if the infected animal showed evidence of “generalized” TB, it was condemned and destroyed. For animals infected with localized lesions, the part(s) were condemned and the rest of the carcass went to market.

As a veterinarian with a passion for improving livestock agriculture in my island, I was truly convinced of the benefits of the water buffalo to the agricultural economy. The animals were hardy and could adapt to just about anything. I figured that if they could thrive under adverse conditions that they have got to be special and I was determined to improve their genetic traits. There was very little published about them at that time, because water buffaloes were predominantly raised in underdeveloped countries where little research is conducted. There were two “breeds” that I was interested in – one was the Asiatic or Swamp buffalo, and the other was the Indian or Riverine buffalo. India at that time had half the world’s water buffalo population, approximating about 60 million head. The Indians were eating the meat because they were not cattle and were not prohibited by religious decree. In India, Hindus do not eat meat from cattle because the animal is sacred and revered. I started to modify the water buffalo for tropical meat production. These animals were so hardy and able to adjust to varying environments and resistant to diseases that they became the logical choice and an important part of my life’s work.

A company started to make beer in Trinidad, later called Carib – a popular beverage for beer lovers throughout the Caribbean. The residuals from beer-making were usually discarded. I began to take that left-over residual and feed it to the water buffaloes; they thrived well on this feed supplementation. I was convinced that I was on the right track. This was the initiation into the development of a beef-type water buffalo. I was encouraged by the nutritional gains made to help transform these animals to look like traditional beef cattle. My college courses at Guelph, where I majored in animal husbandry, included a lot of judging of beef cattle that finally paid off.

I began to build an image of water buffaloes and promote them as beef-type animals. That was unheard of because it did not fit the traditional pattern and use of water buffaloes. The first quarters (withers) of the water buffalo was very high and there was somewhat of a hammock back and when you got to the hook bone they sloped right down severely onto the thin bones where the tail is located. I tried to straighten that up because once I accomplished that trait over the years genetically, there would be much more good meat on the rump. The feat I was able to achieve over the years by selective breeding and some of the water buffaloes that I developed were approaching an ideal beef-type animal.

In the process I made mistakes, but I was able to straighten them out in time. Interestingly, the whole herd that I was working with was completely inbred because no buffaloes were imported into Trinidad after the last lot in 1948.The choice pieces of beef are loins and are in demand by customers. I also selected other traits to improve characteristics into the buffalypso herd. When we compared the Jamaican Red, the Zebu, the Jamaican black and Holsteins with the buffalypso using grazing criteria and weight gains, the buffalypso performed better. The beef cattle were gaining 1.4 pounds of weight per day, while the water buffaloes were gaining 1.6 pounds.

One reason for the differences is that cattle during grazing are somewhat selective, whereas the water buffaloes would eat anything.

In Venezuela, the ranchers used water buffaloes to follow cattle in pastures. When the cattle were finished grazing one pasture, they were then transferred to another pasture and the water buffaloes would be brought in to consume everything left behind. A point of interest is that water buffaloes will consume grass that cattle would not touch, making this behavior a distinct advantage over cattle, especially in regions of the tropics with limited good pastures. In addition, I started to feed the water buffaloes on the residue of sugarcane, called bagasse – it was when all the juice was squeezed out of it and the pith was all left. We added molasses to the bagasse and also used chicken manure because it is very high in nitrogen and a good source of protein. The animals were fattening very well on this ration. The buffalypsoes had terrific digestive systems and over time improved dramatically. We decided to start exporting them. In Venezuela, the ranchers used water buffaloes to follow cattle in pastures. When the cattle were finished grazing one pasture, they were then transferred to another pasture and the water buffaloes would be brought in to consume everything left behind. A point of interest is that water buffaloes will consume grass that cattle would not touch, making this behavior a distinct advantage over cattle, especially in regions of the tropics with limited good pastures. In addition, I started to feed the water buffaloes on the residue of sugarcane, called bagasse – it was when all the juice was squeezed out of it and the pith was all left. We added molasses to the bagasse and also used chicken manure because it is very high in nitrogen and a good source of protein. The animals were fattening very well on this ration. The buffalypsoes had terrific digestive systems and over time improved dramatically. We decided to start exporting them.

The first lot we shipped overseas was in 1956 to Columbia. We further expanded the exports to 19 different countries, including the USA, Cuba, Venezuela, and countries of South and Central America. The importing countries have all been very satisfied with the buffalypsoes. They can work, and their milk is also excellent with a high butterfat content. In the South American countries, for example, Venezuela, the importers made queso de mano and queso blanco. These are white cheeses and very popular with consumers. It is also well known that all the Mozzarella cheese made in Italy is from water buffalo milk. They are well diversified and useful animals in agricultural development. If water buffaloes were indigenous to developed countries, I do not think that cattle would be as popular as they are because they [buffalypso] thrive on rough pastures unlike beef cattle.

For many years water buffaloes were often referred to as “bison” or “hog cattle.” Their fat is always white and that is an advantage because in traditional beef cattle breeds, the only time you get white fat is in cattle that have been force fed and fed on special rations, otherwise the fat is usually yellow. When you buy premium cuts of meat, the fat is usually white, because the animals were fed a better type of food which results in a higher plane of nutrition. We have a huge Muslim population in Trinidad. Religious practices prevent the eating of pigs (hogs) or of touching hogs. I recommended that we do not associate the name “hog cattle” with the water buffaloes to avoid confusion. The next name was the bison, which got confused with the American bison that runs on the plains of the United States. I had to get rid of that name also.

I eventually ended up calling our beef-type water buffaloes – the buffalypso. The logic in the name was that Trinidad was the birthplace of the calypso.

Buffalo Soldier Buffalo Soldier

Stephen Penlyn Bennett (January 28, 1922–December 18, 2011), received many awards for his contribution as a pioneer in veterinary medicine and as the man who developed the buffalypso, among these are the Chaconia Medal, Gold (1984) from the Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, and an Honorary Degree from The UWI (2001). There is also a Steve Bennett building at the School of Veterinary Medicine.

He received his diploma in animal husbandry from Guelph University and returned to Trinidad, where he soon went to work at what was Tate & Lyle, a British company primarily involved in the sugar industry. A July 1971 bulletin issued by Caroni Limited and called “Birth of the Buffalypso,” carried a foreword by Gordon Maingot, the Managing Director, that said:

“Last year, a controlling interest in Caroni Limited was purchased by the Government of Trinidad & Tobago from Tate & Lyle with public funds. This in effect means that the people of Trinidad & Tobago now control the means of production in one of the nation’s most vital industries.

“The Company has since adopted a new emblem. It features the head of a ‘Buffalypso,’ a special type of beef buffalo that Caroni Limited has been developing over the past 20 years. This emblem will serve as a reminder of the new position of Caroni Limited as a full-fledged corporate citizen of Trinidad & Tobago.

“It is appropriate, therefore that this bulletin should describe the development of the unique Trinidadian Buffalypso.”

Although he had been primarily a man of the horses – and remained one until his death – he became a key figure in Caroni’s growing cattle interests and was able to change the way in which herds were housed and nourished, which was followed by livestock farmers in the country. His life’s work was centered on developing the strain of buffalypso that emerged from his breeding experiments with six of the breeds originally imported from India. Indian water buffalo had first come to Trinidad in 1905 and by 1919 they were put to work on the sugar plantations, a replacement for the Zebu who were dying in large numbers from tuberculosis. (It was the same principle on which Indian indentureship was based.)

From the various accounts of the work he did, and the obstacles he surmounted, it is clear he was an extraordinary man with an indefatigable spirit and a strong sense of confidence in his capacity to persuade even the most cynical.

His personal story and the development of the buffalypso is a rugged saga, the kind associated with pioneers, frontiers and immigrants… but it does not have a happy ending.

|