|

|

|

|

April 2019

|

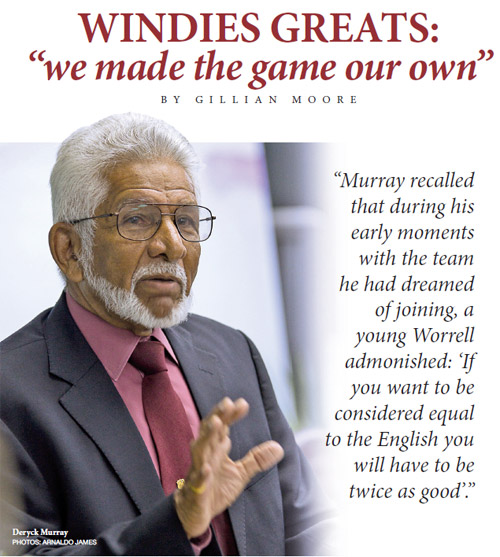

This topic was discussed at The UWI’s Alma Jordan Library on February 14 when the Department of History hosted a panel discussion: “Experiences of Cricket, Colonialism and Nationalism”. It was part of “History Fest 2019”, a series of events and activities hosted by the department from February 11 to 15 under the theme “Sports, Resistance and Nationalism”. Dr Claudius Fergus, former Head of the History Department, introduced guest speakers Deryck Murray and Philo Wallace, saying the former West Indies players represented the emergence of the spirit of Caribbean nationhood. Fergus traced the 200-year history of the game in the region, noting that “it was the domain of white elites before the African working class” were allowed to participate. Even so, recognition was slow in coming. “Cricket represented British culture and authority,” he said. “There was always a white captain.” He said CLR James was among those at the forefront of calls for a black player to lead the region. Frank Worrell took on the captaincy in the 1950s. Murray recalled that during his early moments with the team he had dreamed of joining, a young Worrell admonished: “If you want to be considered equal to the English you will have to be twice as good." Fergus traced the development of the game in the islands, saying, “Trinidad was critical in breaking the hegemony. Teams like Queen’s Park Cricket Club and Stingo Club were pioneers in desegregating sport.” The clubs were also beacons of regional integration, as “many players came from other islands to Trinidad.” He said through their play, they developed “a sense of Caribbean identity”. Murray said there was a “real linkage between colonialism and cricket,” but noted that we had “adopted and adapted the game to our own style”. He said through playing the game we had “developed our own nationalism and regional pride that drove us to become the best”. He linked the rise of the game and the mixing of athletes from different islands to the push for regional Federation around 1960. He said West Indies Cricket and the University of the West Indies were the two main institutions that had survived as unifiers in the Caribbean. He contrasted the “glory days” of the regional game with the recent struggles of the team. “When we lose, it hurts.” “It appears to be a lack of pride.” Murray lamented the fact that politically we had not yet had the leaders who could bring us together more meaningfully, but said, “one day that will come”. Held annually by the History Department, History Fest celebrates our Caribbean past and contemplates its legacy today through panels, workshops, tours, school competitions and book launches, all open to the public.

Speaking at the panel discussion, Philo Wallace recalled the immense honour he felt after, growing up in Haynesville, Barbados (and emulating Windies great Desmond Haynes, for whom the town was named), he joined the team. “It was my dream to represent the great nation of the West Indies,” he said. He too said Caribbean pride meant the old “colonial masters’ were the team to beat: “When we beat England, we beat that entire mindset.” “We have come a long way in breaking the status quo.” Wallace said he was encouraged by the team’s recent Wisden victory and hoped the success would continue: “We have talented people. We need to support them.” He alluded to his post-cricket administrative and academic career, saying, “We have to face reality, cricket is not a (long-term) job.” Aiming his words at current and future WI players, he asked, “are you just going to take home your pay packet, or do you want to take a pride?” He noted that sponsorship had become harder to come by because of poor performances. “Everybody wants to be part of something good. If the product is not good nobody will want to come on board.” Wallace encouraged young players to “strive to be number one. If you are not number one you are not good enough.” Both Wallace and Murray bemoaned the fact that administrators seemed to be actively discouraging today’s young players from seeking advice from their predecessors. They encouraged this interaction as a vital piece of the WI pride puzzle. “Come to me now,” Murray said, “while I am alive.” Gillian Moore is a writer, editor and singer-songwriter. |

Cricket is one of the most iconic parts of our colonial history. Yet despite colonialism’s negative connotations, few aspects of West Indian life are as linked with our sense of self, of nationhood and pride.

Cricket is one of the most iconic parts of our colonial history. Yet despite colonialism’s negative connotations, few aspects of West Indian life are as linked with our sense of self, of nationhood and pride.  This year’s History Fest included a cricket competition between history staff and students, a lecture on the 100-year anniversary of the 1919 protests by Professor Kelvin Singh, a lecture by Professor Brinsley Samaroo on the 150-year anniversary of Mohandas Gandhi’s birth, a tour of Queen’s Park Cricket Club Museum, and a screening of the cricket film Fire in Babylon.

This year’s History Fest included a cricket competition between history staff and students, a lecture on the 100-year anniversary of the 1919 protests by Professor Kelvin Singh, a lecture by Professor Brinsley Samaroo on the 150-year anniversary of Mohandas Gandhi’s birth, a tour of Queen’s Park Cricket Club Museum, and a screening of the cricket film Fire in Babylon.