T&T’s revolutionary milestones were in focus last month when the Department of History in the Faculty of Humanities and Education hosted its sixth annual History Fest themed The Many Shades of Resistance.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the 1970’s Black Power Revolution, as well as 30 years since the attempted coup by the Jamaat-al-Muslimeen in 1990. Both historic moments were re-examined in two notably different discussions.

The five-day History Fest centred on paradigm-shifting events such as the 45th anniversary of the labour revolt known as Bloody Tuesday — with surprise guest panellist, former Prime Minister Basdeo Panday; a documentary screening celebrating the 100th anniversary of the birth of Hindu activist, politician and businessman Bhadase S. Maraj; and a panel discussion on the 100th anniversary of the abolition of Indian Indentureship.

Activities culminated with a spoken word poetry competition in the auditorium of the Centre for Language Learning (won by Tsehai Ze Ollivierre from Scarborough RC Primary and Rochelle Rawlins from Holy Name Convent, PoS), and a cricket match between lecturers and students where History Department students narrowly defeated the ‘History Hitters’.

History Fest 2020 also placed a spotlight on inter-generational perspectives. While early events were in large part nostalgic trips by movers and shakers of the times, later discussions saw students grappling with significant national episodes that had occurred before their birth.

At the festival’s official launch on March 10, political activists, trade unionists and cultural aficionados gathered in the AV Room of the Alma Jordan Library to look back on 1970, the consciousness-raising era that sparked much social upheaval in the post-independence era.

One of the leaders of the 1970 movement, Khafra Kambon, Senior Advisor on Pan African Affairs of the Emancipation Support Committee of TT (ESCTT) and ormer director of ESCTT, described how members of the Guild of Undergraduate Students at The University of the West Indies, “in alliance with trade unions and grassroots organisations,” joined to form the National Joint Action Committee (NJAC), and led a “revolutionary struggle that reverberated through the Caribbean”.

Through mass demonstrations, they beckoned to the youth of the country to rebel against the “Colonial hangover” that saw political, economic and social power remain in the hands of the white minority.

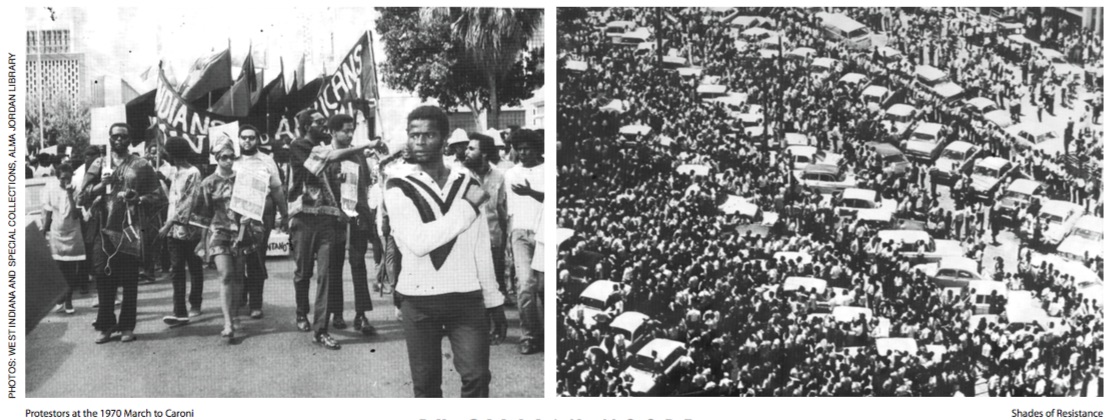

One notable demonstration saw the largely Afro- Trinidadian protesters marching to Caroni in a gesture of solidarity with the Indo-Trinidadian citizenry.

Kambon relayed how these activities took place “within a global context” that included white students of Marx and Lenin struggling against imperialism, the push for independence among nations in the so-called “Third World”, and young Black Americans militantly advocating for rights. Among these latter was another T&T son, Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael), a student activist in Canada credited with coining the term Black Power, who “touched a chord” here in T&T and around the world, inspiring millions.

He said their movement kindled “a progressive undercurrent that despite some reversals, still remains”.

Montsho Masimba, NJAC General Secretary, stirred controversy during his remarks when he claimed the organisation “was not an African organisation” at its genesis, but focussed on the concerns of “the person” above economic machinery.

He said he hoped society could “embrace the lessons of revolution and pass them on to today’s children”.

Both Kambon and fellow panellist, poet and cultural activist Eintou Springer, vocally disagreed with Masimba, stressing that their uprising always had African identity at its core.

Springer said, “Young Black people joined NJAC because it was perceived as African. It was a place for African pride.

“I feel betrayed by the notion that it is not African. There is no dichotomy between standing strong in who you are and holding the hand of your other brother and sister.”

She recounted the inspiring and at times painful history of the Black Power movement in the form of a rousing, rhythmic poem.

By contrast, the Student Forum on the 1990 Attempted Coup, held on March 12 at the same venue, featured few reminiscences, as the participants only had their research to go on.

History Department scholars Michael Reyes, Teja Persad and Andrew Jodhan shared their perspectives on the coup attempt.

Reyes described “those fateful six days” that “brought our innocence to a close”, drawing the historical, political, economic and social picture that created the backdrop for the overthrow plot.

Persad delved into the psychological and social effects of the rebellion, the lingering trauma that followed the shock of killings, looting, fires in the capital, the arming of child ‘soldiers’ — and an atmosphere of mass uncertainty and terror.

Jodhan examined the aftermath of the insurrection, the legal battle that went all the way to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and saw the participants in the uprising ultimately walk free.

Journalist John Victor, who moderated the Commission of Inquiry into the 1990 Attempted Coup in 2014, shared his general impressions remotely via internet feed.

But it was the students who had to come to grips with the final question: should the participants have been forgiven?

Taking into account the economic and social factors, including the potential for retaliatory activity, the consensus was in the affirmative.