Intro:

The University of the West Indies is taking the reins in the global movement to preserve our environment by establishing and funding environmentally focused programmes and research to help educate our society on the bounty of natural resources at our doorstep. Serah Acham speaks with three UWI students who have turned their postgraduate research projects into a bid to preserve the wildlife of our twin-island nation.

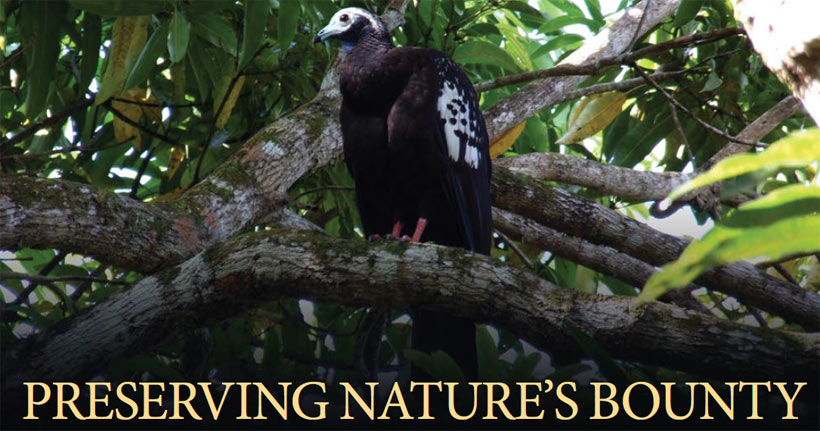

Kerrie Naranjit

Tell us about your project.

My project assesses the phenology of the Trinidad Piping Guan (Pawi). Phenology is the study of plant and animal life cycle events and how these are influenced by seasonal variations. The Pawi is a large forest bird endemic to Trinidad (found only here) and it’s critically endangered, with less than 200 left in the world. They’ve become endangered because of hunting and habitat loss. It’s illegal to hunt them, but it has been going on.

My project is basically looking at the ecology of the bird so that we can learn more about it to develop better management plans for the species.

Although there’ve been other projects on it before, they’re usually short-term, so this is pretty much the longest project on a single population of birds. I’ve done more than two years’ field work at Grande Riviere and Morne Bleu. Those are two sites where they’re regularly seen.

My fieldwork included field studies where I would go out there every morning – they’re most active in the morning, so I did most of my observations from sunrise, about half-five, to about nine o’clock. If I did see them, I’d observe their activities – whether they’re feeding or preening or anything like that – what they’re feeding on, where they are in the area, if there are any preferences for parts of the habitat, how they interact with each other, how they interact with other species and stuff like that. What I’m doing right now is analyzing that data so that if we get a better idea of what their behavior is like and of their habitat use, we can put good management strategies in place for them, because it’s really important right now to increase their population.

Why did you choose this topic?

When I was looking for my M Phil project, the EMA (Environmental Management Authority) decided to fund several Environmentally Sensitive Species projects, so there was funding available for it. I also did my undergrad project on the Pawi in Grande Rivere and enjoyed it. So it seemed a logical choice. I was financially supported by the World Pheasant Association and the Pawi Study Group, which is a local group that deals with conservation of this one species.

How has your personal experience been working on this project?

Well I’ve always been a field person, so it was the ideal project for me in some senses. But there are always the difficulties of having to get up early in the morning, climb a hill before sunrise in whatever weather, with insects around, when you may or may not see what you’re looking for. I have been exposed to a lot of things that a lot of people don’t get to see, just from working out there, a lot of birds and other animals that are in the forest, and working with community members who are trying to make the most of the situation. The same people who might have hunted them in the past, are actually trying to build up eco-tourism.

I lived in Grande Riviere, a rural village on the North coast of Trinidad, for most of the project. I came home every other week. I lived in an interesting house. My bedroom was part of the living room and we had chickens living inside and stuff like that. But it was a very, very safe place to live. The villagers are very friendly, so I felt comfortable.

The difficulty is when you’re actually all by yourself and you have to go up there and sit down and look and wait. You learn to be patient. You find ways to occupy your time. Sometimes you don’t see them (the Pawi) at all for days.

I came across snakes and other forest creatures. I actually came across a Mapepire (a poisonous snake) practically on my shoe because I walked into it without noticing and luckily just happened to stop. I was looking for something, or listening for a sound, and then I looked down and the Mapepire was right on the edge of my shoe, so I just stepped back. It was a small one, but you do get bigger snakes as well. I never got close to bigger ones really … well that I knew of.

What did you like most about working on your project?

Being outside. I learnt a lot about my birds. I enjoyed that a lot. I did a lot of photography up there. I actually do photography now – that kinda grew out of being out there. I was always interested in photography, but I didn’t really start anything professionally until I got up there. I also got a lot of practice and experience with the project itself. You have to take pictures of every Pawi that you see pretty much.

I think the experience also increased my sense of responsibly for conservation and environmental issues. Working with a rare and endangered species is unique and rewarding. The people I worked with, both in the field and out, have helped build me into who I am proud to be today and I hope to continue working with them to rescue this valuable species, and to encourage personal involvement in conservation and environmental issues in as many people as possible.

Michelle Cazabon-Mannette

Tell us about your project.

I’ve been studying two species of sea turtles that we have locally – Greens and Hawksbills. They live close to shore, feeding on the reefs and sea grass bed habitats that we have around Tobago. I’ve been doing my Master’s research studying their distribution on reefs around the island, as well as their abundance, so how many of them there are in one location compared to another. I’ve also been collecting some samples to study their genetics – comparing them with nesting populations and other foraging aggregations around the Caribbean. I’ve also been looking at their value to the economy through fishing, because fishermen still capture turtles for sale for their meat, and I’ve been comparing that with their value to scuba divers because scuba diving is a growing industry in Tobago and turtles are a very popular thing to see to a diver.

Why did you choose this topic?

I wanted to continue with research after doing my undergraduate research project – I really enjoyed that. I was hoping to find something marine oriented and maybe I could tie in scuba diving. I also wanted something that I thought would be important for Trinidad and Tobago, especially conservation oriented, and I know that sea turtles have hardly been studied locally, besides nesting beaches. A lot of work gets done on leatherbacks on the nesting beaches here but those are turtles that come here every three years, nest and leave – each after only spending a couple of months in our waters. The green and hawksbill turtles we have are here year round, living around both islands and they’re subject to the local fishery.

How has your personal experience been working on this project?

For about a year and a half I was living in Tobago and just coming back to Trinidad for short breaks in between. I love to scuba dive and that was a big part of my method. In order to estimate the distribution and abundance of the animals, I would scuba dive at locations scattered around the island with the help of local dive shops and I was able to log over 200 dives doing that and it’s something I love.

I loved being in the water, being able to observe turtles as well as other animals and interact with them. I also got to meet a lot of great people in Tobago. The local dive masters who work at the dive shops helped me out a lot. I was also able to help educate them about turtles and they like to learn about it so that they can teach their customers. I was also able to talk with a lot of visiting scuba divers. We get a lot of divers, both from America and Europe, so I would interact with them, interview them for my survey.

What did you like most about working on your project?

Scuba diving and being able to handle the turtles. In order to get the tissue samples for the genetic study, I would have to capture them. I was also tagging them so I could see, if I recaptured them, if they had changed location. That gave the divers who were on the boat chance to interact and learn more about the turtles as well. I tagged over 50 turtles – mostly medium-sized to small ones, but a few adult-sized ones that were quite big and required help to get on the boat.

I’m glad I was able to be involved in this – it’s the first time that we’ve done any studies of these turtles. I think it’s very important work that needed to be done because turtles are a shared resource really. They don’t live here all the time. They move hundreds, thousands of kilometres across the Caribbean Basin. So having an open fishery here for example, we’re not just affecting our stocks of turtles. We’re depleting stocks of turtles from other locations where they might be trying to protect them. It makes no sense for each country to be managing the turtles differently. We need to have a regional management programme, otherwise the work at one location is not going to do much. We have to protect them everywhere that they’re found.

Lee Ann Beddoe

Tell us about your project. Tell us about your project.

Overall, what we’re doing is looking at a methodology for restoring coral reefs, because they’re degrading due to anthropogenic (man-made) and natural causes. We’re trying to find the fastest method for reversing this deterioration, and what we’re using is electrolytic mineral accretion using low Direct Current (DC), to enhance the growth of the corals.

Our experimental site was based in a man-made bay in Tobago – Coconut Bay. We were using electricity from a dive shop and it was converting the household electricity (AC) to DC before charging the corals. This incorporated physics so the Physics Electronics Workshop helped us with that configuration. And using cables, we ran the electricity to the experimental site.

We needed a species of coral that was fast growing, but not endangered, so we used fire coral, also called Millepora alcicornis. We ran electricity to 40 individual pieces and had 40 pieces which acted as the control and received no electricity. We compared the growth changes every two weeks for 1 year.

We then used a Scanning Electron Microscope and X-Ray Diffractometer, through the Physics Department. So we had photos showing the skeletal structure of the coral that received electricity vs. the control, as well as the chemical analysis. At the end of the experiment we crushed different aspects of the coral to determine the composition, and we found that it was very similar to the natural growing coral. That’s good because Buccoo Reef is a major tourist attraction and everybody depends upon reefs for the goods and services they offer, like fishing, scuba diving and tourism. That’s good in terms of having a regional impact as well.

Why did you choose this topic?

I wanted to do a research project that wasn’t just going to collect baseline data and sit on a shelf. I wanted to do something applicable to protecting the environment. So Prof Agard [John Agard, Head of The UWI Department of Life Sciences] suggested exploring the idea of mineral accretion.

What I liked about the project was that it pulled from different disciplines, even chemistry.

How has your personal experience been working on this project?

When I started the project I thought “ok, I’m going to do research that would help the environment.” I didn’t take into consideration the social aspect, but being in Tobago I have learnt about it. Tobagonians take a lot of pride in their environment and conserving it – they depend on their natural resources for tourism etc. They’re very, very cooperative when it comes to doing research that could help preserve their resources, so I learnt about the people who actually use these resources and how much they depend upon them to feed their families. It inspired me to further my research in the Marine field, but more so Environmental Biology.

There’s also the educational aspect because I got to teach people about different things and why we need to do this. Tourists especially were very interested and they were pleased that people were doing research like this.

I was a demonstrator and teaching assistant for a Marine Ecology course in the department and I asked students from that class to come and help me with my project. They learnt the technique of buoyant weighing and measuring corals, how to handle certain coral species with care and some of them actually learnt to scuba dive. I also advanced my scuba diving and learnt about coral species. I learnt new things from Physics. It was an exchange of knowledge.

I went to the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences to do some training – a Coral Reef Ecology course for three weeks. I got a partial scholarship and UWI provided the rest of the funds to travel, and it was fantastic. I met other students doing research in the marine environment and networked with other marine scientists.

It sounds like fun.

Oh definitely! I have pictures of creatures that are on my research. A sea horse came and he actually started living on it (the experimental site), so it was good for the dive shop because when they teach their beginner divers, they take them on the experiment site and they would see the sea horse. We call him Sea Biscuit. We also had squid, starfish, several species of reef fish and a moray eel that would come to visit from time to time.

Photo: Kerrie Naranjit ©

|