Pesticides – the word conjures up notions of contaminated crops and at-risk consumers: but what about the farmers themselves? What about those whose livelihood depends on using these sometimes hazardous agents to keep their produce free of disease? In the farming community here and globally, pesticides have caused acute illnesses like headaches and vomiting, and even chronic ailments that hinder farmers’ health for long stretches. Pesticides – the word conjures up notions of contaminated crops and at-risk consumers: but what about the farmers themselves? What about those whose livelihood depends on using these sometimes hazardous agents to keep their produce free of disease? In the farming community here and globally, pesticides have caused acute illnesses like headaches and vomiting, and even chronic ailments that hinder farmers’ health for long stretches.

For some time now researchers in UWI St Augustine’s Faculty of Food and Agriculture (FFA) have not only been developing a non-hazardous biological (as opposed to chemical) agent to treat local farmers’ crops; they have been actively in the field sharing the agent with farmers, monitoring their results, and working closely with them to improve their practices.

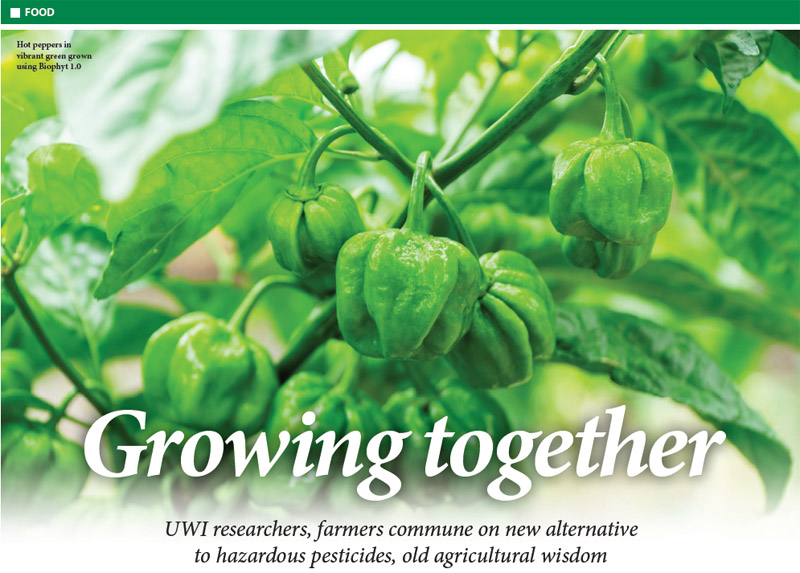

On July 24, 2019, this community of farmers and FFA personnel met for a workshop at UWI’s Innovation Park in Orange Grove. The workshop’s theme was “Alternatives to Hazardous Pesticides in Vegetable Disease Management”. The “alternative”, developed by FFA, is named Biophyt.

“Biophyt 1.0 is like Windows 98 computer software, there will be different versions and iterations as time goes by,” Dr Duraisamy Saravanakumar, Senior Lecturer (Plant Pathology), told an audience of farmers, FFA staff and other stakeholders.

Farmers like 30-year-old Romona Branche, who was part of field testing done from November 2018 to June 2019 to examine its efficacy in the control of Phytophthora rot in hot peppers.

“The yield was really big, a hundred crocus bags per picking. Almost like sweet pepper.”

She was happy that she had no major adjustments to make like buying new equipment, as all of her old gear could be used with the new treatment. Additionally, Romona noted that fungicides and pesticides are costly and Biophyt 1.0 was less per bottle so overall the cost for her was much lower.

Smiling, she said, “Even the stalks were healthier and fatter. The plants were taller and had a lot of flowers.” Romona speculated that the pesticide might even be safer for the bees and increase pollination.

The control areas of hot pepper, where traditional pesticide was used for comparison, yielded less produce.

On another farm, Azir Hosein, 35-years-old, was engaged in field testing as well. His parents, Tasslina and Sookraj Popalie, own approximately five acres in different areas from Orange Grove to Aranguez. They tested Biophyt on tomatoes.

“It was great!” Azir stated. “The taste of the tomatoes is very sweet. Our customers say they purchase from other farmers but theirs is bland – our tomato is sweet.”

Tasslina joined in, saying “this crop was a bumper crop. It lasted more than six months.” The duration of the trials was three months. The bio-agent was tested on one acre of tomatoes. The farming family reported a yield of 100 crates in total over only two or three pickings. They admit that the control group was just as good, but perhaps weather was a factor.

Farmers like Azir, the Popalies and Romona deal with unpredictable risks all the time. Pathogen and pest management however, are factors they can manage and perhaps, Biophyt 1.0 can not only help increase their yields, but also be a healthier alternative in the long run.

Farmer’s challenges

Apart from the UWI-developed bio-agent, the workshop also addressed several issues affecting farmers. Dr Saravanakumar noted that when surveyed, 34 per cent of farmers indicated that the high cost of inputs were an impediment. 20 per cent said that there was poor access to roads. 18 per cent indicated that production was challenged by pests and diseases. Other prohibitive factors included praedial larceny and market prices.

In his presentation, Dr Saravanakumar explained the proper use of pesticides. Instinctively, he said, we think that increasing pesticides will kill more pathogens. However, the pathogens develop resistance and more harmful pesticides go into the soil and into the water, leading to toxicity. The solution would be to ban registration of harmful pesticides and to develop alternatives.

The feasibility of using the healthier alternative Biophyt 1.0 was met with skepticism, “Monsanto just lost two billion-dollar lawsuits and we are still selling Roundup,” a farmer commented. Roundup is a popular herbicide used for decades which according to the Guardian UK, Bayer now produces since they acquired agrochemical company Monsanto. The company is facing more than 9,000 lawsuits across the US from mostly former gardeners and agricultural workers who believe that Roundup exposure caused their cancer. The feasibility of using the healthier alternative Biophyt 1.0 was met with skepticism, “Monsanto just lost two billion-dollar lawsuits and we are still selling Roundup,” a farmer commented. Roundup is a popular herbicide used for decades which according to the Guardian UK, Bayer now produces since they acquired agrochemical company Monsanto. The company is facing more than 9,000 lawsuits across the US from mostly former gardeners and agricultural workers who believe that Roundup exposure caused their cancer.

Dr Saravanakumar’s response was measured, stating that when we take national decisions we cannot take them based on a court action as some court actions are later overturned. We take national decisions based on scientific findings.

He also noted that Small Island Developing States (SIDS) may not have the economic wherewithal to do all the scientific investigation for significant enough findings to declare pesticides as hazards. But while we cannot pull existing pesticides from shelves, we can reduce the reliance and dependence on pesticides by developing viable alternatives.

Better practices

In engaging with the farmers and fielding their questions, Dr Saravanakumar attempted to counteract poor cultural practices while affirming some of the traditional folk knowledge of the farming community. “It is important to not only get quality labour on a farm, but also to know why you do what you do,” he said.

He encouraged the planting of botanicals or flowering plants like marigolds alongside the crops as this attracts beneficial insects and helps to control pests. This resonated with the audience. A farmer shared that one should plant African and French marigolds in particular and “this is why some of the older generation plant ‘Stinking Suzie’ in their garden.”

He spoke of covering irrigated soil with a plastic sheet for six weeks to raise the temperature, trap the heat, and in so doing kill pathogens which would have been dormant under the soil but developing strong structures.

He also advised farmers to avoid sprinkler irrigation at night as the increased humidity will lead to leaf wetness and increased pathogens.

Some of the poor cultural practices of farmers were identified in the workshop as well by research assistant Augustus Thomas, another representative from the FFA. These included using dosages of pesticide beyond the stipulated levels, mixing more than one chemical together, applying the pesticide at closer intervals than recommended, and using tractors on multiple farms whereby pathogens can be transferred from infected fields.

Beyond one-on-one outreach, this initiative of the UWI is a part of a larger project spanning 18 countries and funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). This integrated pest management project includes looking at the life cycle of pesticides, triple rinsing containers, removing and destroying obsolete pesticides from the region, training inspectors, generating funding and raising public awareness.

Initiatives like these protect farmers like Romona and Azir. They take us one step closer towards safer food for all.

Dara Wilkinson-Bobb is a part-time lecturer in The Writing Centre in the Faculty of Humanities and Education, where staff and students of the UWI can access free writing assistance.

|