|

August 2019

Issue Home >>

|

For many of us, mosquitoes are a daily annoyance, and one that we would happily stay far away from for the rest of our lives. But Renee Ali looks at these flying nuisances a little differently. A self-proclaimed “Mosquito Girl”, Renee is one of a devoted team of local researchers who are studying these tiny flying vampires to find out more about where they live, what they eat, and how we can better protect ourselves from the many diseases they carry. For many of us, mosquitoes are a daily annoyance, and one that we would happily stay far away from for the rest of our lives. But Renee Ali looks at these flying nuisances a little differently. A self-proclaimed “Mosquito Girl”, Renee is one of a devoted team of local researchers who are studying these tiny flying vampires to find out more about where they live, what they eat, and how we can better protect ourselves from the many diseases they carry.

Mosquito research in Trinidad has a rich legacy passed down by the late Professor Dave Chadee— known to many as the original “Mosquito Man”. Ever been on a plane and saw the flight attendants spraying the cabin before takeoff? You have Professor Chadee to thank for that, as he was responsible for implementing the spraying to cut down on the spread of mosquitoes across countries (by hitching a ride on planes). His contributions to mosquito research have helped people across the world to better understand dengue fever, yellow fever, malaria and Zika, and many of his students have gone on to make incredible discoveries in the field.

“When Professor Chadee died, I didn’t know what to do because I was his last student. I was basically like the baby. I had just applied to do my PhD and just got accepted when he passed away a few months later. I thought I was going to (research) water with him. But everybody but me knew he had this plan,” says Renee. She never expected to be working with mosquitoes— after all, her background is in molecular biology and she had originally expected to work with Professor Chadee. But fate and the professor had other plans.

Three years later, Renee is close to completing her PhD studying the little-known Mayaro virus and its main mosquito vector— a mysterious species called Haemagogus janthinomys. Unlike its famous relative Aedes aegypti, not much research has been done on Haemagogus and the virus it carries. Twenty years ago, Professor Chadee and the Insect Vector Control Division (IVCD) did some investigating on the mosquito species— focusing on its capacity to spread yellow fever and hunting for it in the wild anywhere there were howler monkey populations (as they thought that was its preferred food source). At the time, they didn’t know about its connection to the Mayaro virus, which had only been isolated in Trinidad in 1954 in some forest workers and not found here since, although there have been several reports across South America.

Dr. Judith Gobin, Head, Dept of Life Sciences is extremely pleased that the seminal work that was accomplished by the late Prof Dave Chadee continues to be expanded in the work of our postgraduate students such as Renee. She is convinced that Prof Chadee would also have been very pleased.

A little known species and the virus it carries A little known species and the virus it carries

The trouble with Mayaro virus is that its symptoms are strikingly close to dengue and the chikungunya virus, so it’s proven hard to diagnose. But Renee has had some luck in pulling back the shroud over this little-known disease and its vector species. For two years she was in the field, travelling across Trinidad to look for Haemagogus. “I did a map of Trinidad, divided it into four sections and I sampled North-East, South-East, North-West and South-West Trinidad.”

She found Haemagogus all over, especially in forested areas where she also managed to find Mayaro virus present in mosquitoes. They were abundant in secondary forests, but to her surprise, a lot were found in mangrove areas as well, which means they are adapting to new surroundings.

It was a learning process for Renee, who had never done that type of field work before. The UWI “mosquito team” had a hand in collecting the bugs and getting all the data together— Lester D James, Brent Daniel, Rachel Shui Feng, Nikhella Winter and Akilah Stewart were all crucial to making the project work.

“At first I didn’t know what I was looking for and we were figuring everything out on the go,” says Renee. “Insect Vector’s lab team also really helped me. It was a huge collective effort…. All the molecular biology work I was doing with the mosquitoes— the mosquito team didn’t know how to do that. But I needed to get the mosquitoes first.”

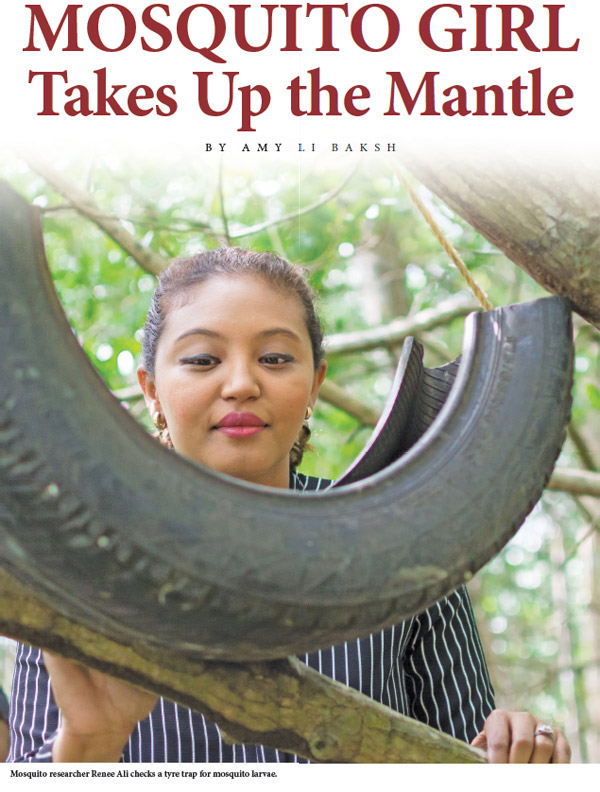

Now at the tail-end of her research, Renee doesn’t spend as much time in the field but she still makes sure to check all her traps regularly to monitor the mosquitoes living in the wild, as well as maintaining her lab-grown colony. She shows me a paper with what looks like small black pen marks all over it, but under a microscope they are revealed to be mosquito eggs.

“I collect the larvae and breed them to adulthood. I have over 1000 eggs here, so I now have to hatch them to start another colony. We use tyre traps out in the field for two weeks, and then we collect the water and the eggs.” Tyre traps are a low-budget solution to gathering specimens— cut a tyre in half and hang it from a tree with some water inside. The mosquitoes love the dark spaces and still water, so there’s always something to find when she goes in to collect samples. But when she started out, she had to do things a little differently.

“In the beginning I was using traps, but wasn’t getting much success, so I thought maybe I’m doing something wrong— or maybe they’re just not there,” she says. But one day, she was visited by Professor Chadee’s mentor, Dr. Elisha Tikasingh. “He said, you’re going about it wrong… you have to actually sit there and let them come to you to bite you. Just look up into the sunlight around their biting hours, and they will come to you”. And it worked. The tried and true method from the earliest days of mosquito research still stands— they love human bait.

From student to scientist

Dr Adesh Ramsubhag, a senior lecturer in the Department of Life Sciences and the one who got Renee to come back to do research at The UWI in the first place, remembers her start as an OJT in the labs. “She demonstrated her potential as a scientist, working systematically and diligently to successfully extract high quality DNA from challenging materials including asphalt and crude oil. She was then encouraged to pursue the PhD in the area of microbiology of water quality.” Dr Adesh Ramsubhag, a senior lecturer in the Department of Life Sciences and the one who got Renee to come back to do research at The UWI in the first place, remembers her start as an OJT in the labs. “She demonstrated her potential as a scientist, working systematically and diligently to successfully extract high quality DNA from challenging materials including asphalt and crude oil. She was then encouraged to pursue the PhD in the area of microbiology of water quality.”

But sometimes life has another plan, and she ended up with mosquitoes instead. “They’re really miserable… but I love them!” she laughs, remembering the endless bites the team suffered while collecting their data for the project.

Now that the research is mostly complete, people have started to take notice. Renee’s first article, titled “Changing Patterns in the Distribution of the Mayaro Virus Vector Haemagogus Species in Trinidad, West Indies” was accepted for publication in Acta Tropica, and she has just found out that she has won an award: The 2019 ACME Young Investigator Award— International Student Travel Award (granted by the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene).

Hard work and many, many mosquito bites are coming to fruition. And just in time, too. With the spread of mosquito vector diseases across the tropics, it is more important than ever to monitor these insects and the diseases they carry— so if there ever is a local outbreak of the Mayaro virus, we will be ready.

As Dr Ramsubhag puts it, “The results so far have been very significant in terms of understanding the distribution, ecology and the range of viruses associated with Haemagogus mosquitoes. The data generated can now be used by the IVCD for risk assessment and development of management systems to mitigate any future outbreaks of these viruses.

This project can be a model for cooperation and collaboration between governmental agencies and academia where we can apply our advanced technological capabilities to help provide solutions to problems faced by the society.”

I don't know about you, but I'm buzzing to see what they find next.

Amy Li Baksh is a Trinidadian writer, artist and activist who makes art to uplift and amplify the unheard voices in our society.

|