UWI scientists make major contribution to 2022 UN climate report, highlight urgent need for change to protect the Caribbean

“Every part of the planet and all human beings are affected by global greenhouse gas emissions, which are the highest they have ever been in human history,” said Professor Michelle Mycoo, a professor of Urban and Regional Planning in the Department of Geomatics Engineering and Land Management at UWI St Augustine.

She added, “Urgent action is needed at a global scale to curb the rise in temperature caused by such emissions and to prevent catastrophic outcomes such as ecosystem and infrastructure loss and damage, decreased food and water security, and population displacement.”

Professor Mycoo is one of five scientists from The UWI who contributed their expertise to the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report. The report’s critical message, experts concluded, was that global average temperatures could reach or exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial period by 2040.

The goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius will likely be out of reach by the end of this decade unless countries drastically accelerate efforts over the next few years to slash their emissions from coal, oil and natural gas. Any further delay in concerted global climate action will miss the rapidly closing window to secure a livable world. This will be bad for small islands that are extremely vulnerable to climate change impacts and risks.

Professor Mycoo was the Coordinating Lead Author (CLA) for Chapter 15 of the IPCC report, “Small Islands”. Dr Donovan Campbell, Senior Lecturer and Head of the Department of Geography and Geology at The UWI Mona Campus in Jamaica, was a Lead Author of Chapter 15.

The IPCC is a United Nations body responsible for assessing the most up-to-date scientific research related to climate change. Since its inception, the IPCC has published six reports which form the technical basis for international climate change negotiations. The most recent report was launched earlier this year.

Prof Mycoo and the other scientists contributed to Working Group II (AR6-WG2) under the theme: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Dr Aidan Farrell, Senior Lecturer in Plant Physiology in the Department of Life Sciences (DLS) at UWI St Augustine, was Lead Author on Chapter 5 – “Food, Fiber and Other Ecosystem Products”. Dr Michael Sutherland, Head of the Department of Geomatics Engineering and Land Management, and retired professor John Agard, from DLS, served as reviewers for the report.

The Small Islands chapter grouped countries geographically, putting together Small Island States from the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans. These states are already and will further be affected by increasing temperatures, intensifying tropical cyclones, changing precipitation patterns, sea-level rising, storm surges, droughts and invasive species.

According to Mycoo, many parts of the world are vulnerable, but Small Island States are especially at risk:

“Small Island States are extremely vulnerable because their ecosystems are very fragile. In our assessment, we saw different arenas for action so we do know that at the global level there is a need to stay below 1.5 degrees Celsius. We are aware from the report that we have at least the next decade to curb carbon emissions.”

Professor Mycoo added that in the Caribbean there is a possibility of 100 per cent loss of endemic species if rising temperatures surpass the 1.5 degree marker within the next 90 years. “That’s the extent to which our ecosystems are fragile. We face an existential threat from global warming and sea level rise, and we are extremely vulnerable as a population, but also our biodiverse sensitive ecosystems and our equally fragile economies.”

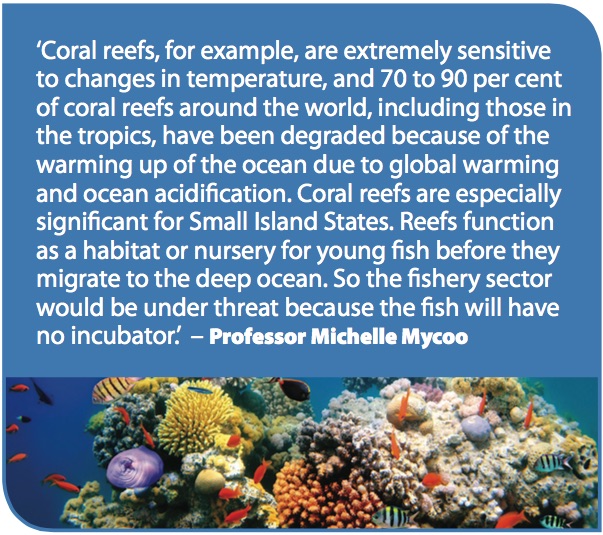

In the Caribbean, coral bleaching is a particular concern.

“Coral reefs, for example, are extremely sensitive to changes in temperature, and 70 to 90 per cent of coral reefs around the world, including those in the tropics, have been degraded because of the warming up of the ocean due to global warming and ocean acidification,” she said. “Coral reefs are especially significant for Small Island States. Reefs function as a habitat or nursery for young fish before they migrate to the deep ocean. So the fishery sector would be under threat because the fish will have no incubator.”

She added, “Also, our beaches are composed of the coral reef that breaks down to create sand which resembles talcum powder. If the coral dies, then it means that beaches will no longer have beach material and that will impact tourism. [Fisheries and tourism] are two critical economic sectors. They are the linchpins of most Caribbean economies. If there is extensive coral death because of ocean warming and acidification, economically we become even more vulnerable.”

Another Caribbean concern is food security. Chapter 5 on Food, Fiber and Other Ecosystem Products noted that the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather and warming oceans are directly linked to slowed agricultural growth and had negative impacts on food production. Areas with the largest impacts thus far include South and Central America and the Caribbean.

According to Dr Farrell, the Caribbean is not only vulnerable because of its geographic position, but also the heavy reliance on imported staples.

“Globally, if we reach 2 degrees of warming, lots of parts of the world are going to see less productivity. Food for everybody will become more difficult. The trade of food might impact small islands even more because they generally aren’t food self-sufficient,” he said.

Farrell added that past reports did not take a close look at crops outside of the main staples such as rice and wheat. In the AR6-WG2, vegetation important to nutrition like leafy green vegetables and Caribbean fruit tree crops were examined.

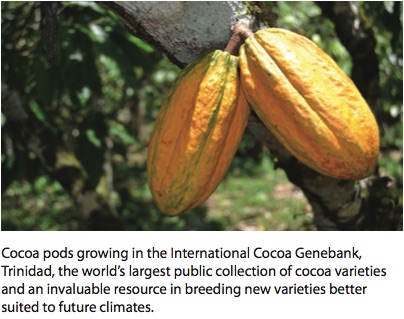

Diverse local vegetation is one way to combat food insecurity.

“All around the tropics, people are realising that agroforestry is also a climate change adaptation. Diversity is a response to climate change. We don’t know when the heat wave or drought will come, so just having diversity makes you more resilient,” said Dr Farrell. He added that “Trinidad already has quite a lot of that in the cocoa agricultural system. In that sense it’s not an adaptation because it was already there, but Trinidad is better off than some islands that don’t have agroforestry, and as long as we can keep those systems, that’s good news for us.”

Another solution mentioned in the report is aquafarming, which would aid in diversifying economies and furthering sustainability. Other options are more complex and call for public education, better governance, legal reforms, more data and Caribbean-specific studies.

“The Caribbean is right at the centre of what the world needs to do because it will likely see the impacts before some other parts of the world. At the moment, I feel that there’s a perception here that adaptation and mitigation should happen elsewhere, but we have moved past the point where you can look at what others are doing. Everyone who relies on the landscape for their livelihood and well-being needs to think how they can adapt. Meanwhile, the message for governments is still: reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” noted Farrell.

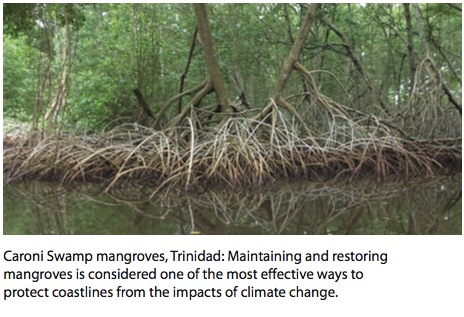

Human settlements, including coastal cities in the Caribbean, roads and airports, as well as manufacturing plants, will require adaptation measures to protect people, economies and ecosystems. These measures include engineering options such as seawall defences and improved drainage infrastructure, combined with ecosystem-based adaptation such as mangrove replanting and watershed management.

None of these measures can be implemented without access to adaptation finance. Which, Prof Mycoo said, “is the elephant in the room”. New strategies are being developed to make it easier for accessing finance from the global community donors.

While the report is extensive, there is still more research to be done. Both Prof Mycoo and Dr Farrell noted that implementation of adaptation and mitigation measures as well as monitoring and evaluation of their effectiveness were keys to success in the fight against global warming.

The report was not only important because of its message on climate change – an historic feat was achieved with its publication. Professor Mycoo was the first Caribbean woman to be selected as a Coordinating Lead Author and was among a growing number of female scientists who authored the IPCC report. When the first report was published in 1990, less than 10 per cent of the contributing scientists were women. On the AR6-WG2, 41 per cent of the scientists were women. According to Prof Mycoo, this is the highest number of women scientists to contribute to an IPCC report. As a CLA, she also made it a point to spotlight women authors and Caribbean scientists. The Small Islands chapter had the highest number of women contributing authors. Of 11 contributing authors to the chapter, 10 were women and three were from the Caribbean.