|

|

|

|

December 2014 |

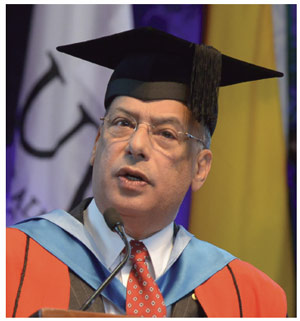

Citation: Sir Ronald Sanders, Degree of Doctor of Letters (DLitt)Chancellor, when Calypsonian Black Stalin sung “Caribbean Unity,” popularly known as “Caribbean Man,” he probably was not thinking of Sir Ronald Sanders. But Sir Ronald would certainly qualify as being among the strongest candidates for the title of Champion of the Caribbean People. And with a career that encompasses broadcast and print journalism, development and commercial banking, diplomacy and international negotiations in both public and private sectors, he might well be deserving of the title “Renaissance Man” as well. Born in 1948 in Guyana, Sir Ronald entered the working world as a broadcaster specializing in news and current affairs at the age of 21. He appreciated that broadcasting was a vital tool for educating and informing the Caribbean people about the importance to their lives of the fledgling Caribbean Free Trade Area (CARIFTA) established in 1965. As a broadcaster and soon thereafter a Programme Director and General Manager of the Guyana Broadcasting Service at the ripe old age of 27 (!), he developed a rigorous approach to researching economic, political, legal and social issues. He has twice served as High Commissioner for Antigua and Barbuda to the UK, as Ambassador to the EU, Ambassador to the WTO as well as Deputy Permanent representative to the UN for Antigua and Barbuda. In the private sector, he has served on the Board of Directors of financial institutions, telecom companies, media companies and a sustainable forestry company in Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Barbados, Guyana and the US Virgin Islands. Sir Ronald has been widely recognised for his contributions, including twice by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, first as a Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael and St. George and later as a Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael and St. George. Further honours include: Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of the Nation by Antigua and Barbuda, Commandeur dans l’Ordre des Palmes Academiques and the Order of Australia by the Government of Australia for services to the Commonwealth and in advancing the interests of small states. His grasp of the complexities of world politics and his insights of the Caribbean place in the puzzle puts his work in high demand on the international lecture circuit. In addressing that need, he has launched his own website where his lectures, interviews and commentaries can be accessed. His work covers subjects as varied as “The Moral Case for Reparations for Slavery” to the need for solidarity in protecting our rum industry to the opportunities and challenges for tourism in wooing the blossoming Chinese middle class. His catalogue of study covers the length and breadth of contemporary issues facing the Caribbean region and the greater Commonwealth in particular. Two roles played by Sir Ronald stand out in a long and distinguished body of work. First is the role he played in leading efforts to block the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) from unilaterally imposing rules governing “tax competition” that would have served to handicap the Caribbean financial services sector. Although that battle was won, the war was ultimately lost. The second was leading the case for Antigua and Barbuda against the United States at the WTO in the overreaching of the US Government in its determination to impose its extra-territorial laws in defiance of its international obligations. Whether as journalist, journalistic director, diplomat, international consultant or research fellow, Sir Ronald has consistently sought to advance the cause of Caribbean integration while working tirelessly for the independence of the Caribbean from external forces. By personal example, he urges us to be not just hard working, not just to excel in our chosen fields but to be courageous and forthright, “bold” even, in asserting our rights as citizens of the world, every bit as capable as a people as any other. Chancellor, I present Sir Ronald Sanders, and ask that by the authority vested in you by the Senate and Council of The University of the West Indies, you confer on him the degree of Doctor of Letters, honoris causa.

I consider myself a consummate Caribbean man. I was born in Guyana with Antiguan antecedents on my maternal side. I have been pleased to live and work in five Caribbean countries, Trinidad and Tobago included. I helped to start and was a member of the Board of the three Caribbean-wide organisations early in my career, the Caribbean News Agency and the Broadcasting Union, and later the Caribbean Financial Action Task Force against Money Laundering and Drug Trafficking. Of the latter two, I had the honour to serve as Chairman. In my diplomatic life as an elected member of the Executive Board of UNESCO; as a negotiator for small and vulnerable economies at the World Trade Organisation; and as an Adviser to the World Bank and the Commonwealth Secretariat on small states, I worked for the entire Caribbean – and more particularly – the West Indies which I regard as my country, my home, my native land. But circumstances did not permit me to attend this University; those circumstances took me to other universities in other lands. I am acutely aware, therefore, that while I have long been a great admirer of The UWI, I am a stranger to its halls. All the more reason, Chancellor, why I am very grateful to the Council of the University for the honour they have conferred upon me by making me a Doctor of this great institution. I have been the recipient of other honours, including two knighthoods and membership of the Order of Australia – each has been special to me and I value them highly. But, I confess that I value this Honorary Degree by The University of the West Indies as especially distinctive, for it comes from an institution that, more than any other, represents the oneness of the West Indian people and the singular value of their unity – two things in which I firmly believe and am resolutely committed. To be recognized by the West Indian people’s University is an honour I shall cherish for the rest of my life. I thank the public orator for his generous words and I thank you – today’s graduands – for allowing me the privilege of sharing this ceremony with you. To all of you graduands, my heartiest congratulations. Here you are today about to be certified by The University of the West Indies. Recalling my own university days, it may be just as well that The UWI certifies only academic accomplishments. I am sure that many of you are entitled to be certified in other fields of endeavour. There is nothing wrong with that. It was all part of the university experience without which your sojourn in its halls would have failed to prepare you for the rest of the lives upon which you are about to embark. You have made many people proud, particularly your parents, your family and your close friends who supported you. Today is as much their day as it is yours. They, too, deserve recognition and congratulations for staying the course with you, and I invite you to honour publicly all that they have done by applauding their support. Can you imagine the relief that some of your families are feeling? All their doubts and fears are gone. Finally, they can look forward to scratching you off their monthly expenditure. My advice? The joy won’t last forever – tap them for a final loan now. Customs officers at airports are usually emotionless and unfriendly characters. But two nights ago when I told the customs officer at Piarco Airport that I was here to participate in The UWI’s graduating ceremonies, his stern posture melted away, and with tears welling up in his eyes, he proudly announced that he had just come from attending his daughter’s graduation with a Master’s degree. I got a warm hand-shake, a joyous smile and a free pass to boot. So, thank you, The UWI. Graduands, you are emerging from a remarkable institution; and you should be proud of the degree you attained. Against all the odds, the UWI is among the first 800 universities in the world. Given that there are about 20,000 universities globally, that puts the UWI among the first 5%. Recognizing the small population size of our region, the paucity of resources and the fact that government funding for research is almost non-existent, being among the first 5% of universities globally is a remarkable achievement. The UWI, as a regional university, has won more grants from the European Union than any other University in the 79-nation African, Caribbean and Pacific group. That is no mean feat. Having spent a period of my diplomatic life negotiating with EU bodies for funding for national and regional projects for the Caribbean, I know the testing – almost forbidding standards – that the EU sets. The UWI’s success with the European Union, therefore, is testimony to the high quality of the projects it has put forward and the intellectual thoroughness of its corroborative arguments. In the last decade the University’s enrolment has grown from 22,000 to more than 47,000 students and applications increased between 2006 and 2013 from 16,000 to 30,000. The University has coped with this rightful demand by West Indian people for higher learning in the face of inadequate funding and competition from new national universities and from foreign ones. There are areas of research in which the University has international standing – among them, sustainable development in small island states; Early Childhood Development, select areas in Law, Marine and Environmental Studies. One can only imagine how many more areas of valuable research for this region the UWI could have developed if it had the funding of governments that it deserves. Few Universities can be good at everything but, as Vice Chancellor Nigel Harris once remarked to me, the UWI has “peaks of excellence in which it is globally visible and about which we can be proud as a region.” So, in being pleased with yourselves, be proud of the University that you have been privileged to attend. It has given you an enviable education in spite of the considerable challenges it faces. In all this, you owe a debt to the men and women on this platform who have dedicated their lives to teaching, to imparting knowledge, and to preparing this West Indian generation, of which you are a part, to participate meaningfully in a highly competitive world. They too should be applauded; applauded particularly by you – today’s graduands – who are the fruits of their labour in the vineyard of Caribbean human development. I enjoin you to do so. I make one further point about this University. It has added considerable value to the talent of thousands of Caribbean citizens who now work in high-flying positions in developed countries. That is a measure of how good the University is. The University has also produced many of our region’s present leaders in government and in the private sector. It has also produced a multitude of men and women who are putting to work for the betterment of our region the knowledge they acquired in this institution. Without this University and all that it does, our region would not have achieved the level of development it has today. In this connection, I recall the words of Thomas Jefferson: “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and will never be.” The foundation of our continued independence, and the knowledge to maintain it in an international community that is neglectful of the plight of the small and vulnerable, begins in this University. That is why our governments must be urged to support The UWI for all the good it delivers. Such support will take many forms, especially money. But high among them – less tangible but no less substantial – must be the preservation and strengthening of a West Indian environment of togetherness. The light rising in the West that the UWI represented at its birth – and that is reflected in its motto – can only continue to shine if the fundamentals of our regional integration project are unshaken. Indeed, I go further to say that our individual countries – always severely challenged to manage each on their own, and now even more gravely confronted – will themselves return to bending their knee and opening their palms just to maintain notional sovereignty. Adapting to the ravages of global warming and climate change, ensuring that terrorism finds no foothold on our soil, coping with diseases that know no borders, fighting drug trafficking and violent crime, bargaining with a global community to whom, as small states we are of very marginal interest – all these things demand robust regional cohesion and collective regional action. Our region will survive – and our regional institutions such as this one – will prosper and deliver for our people, only if our identity as one family, one community, one society, one civilisation endures and strengthens. Providing that environment of sturdy regionalism is part of your generation’s trust – not only as alumni; but also as West Indians. I urge you to accept that trust and to fulfil it in your interest and in the interest of all our peoples – particularly your generation and the next ones to come. Now I come to the part of this speech that troubled me the most. Speakers on occasions such as this one are expected to inspire and motivate; to encourage you to go out and conquer. But, I am mindful that you’re graduating into a tough world where the competition for good jobs is fierce; where the number of available jobs is few; where the economies of our region, with a couple of exceptions, are still reeling from the effects of global recession; and where individual Caribbean countries are too small and too weak to bargain effectively in the international community. That should be sufficient reason for me retreat from this stage in apprehension for your future. But to do so would be wrong. Not wrong because I would leave you in despair, but wrong because I do not believe you should despair. Indeed, I am convinced that it is times, such as these, that provides opportunities. It is a time of dizzying change; change that you have witnessed in your own lifetime. It is times like these when leaders emerge and entire swathes of younger people make changes that suit their own aspirations and shape their own future. It is telling that in talking to a graduation class at Stanford University, Steve Jobs – the entrepreneur behind all the Apple products we know and love – who knew that he was dying, said this: “Your time is limited so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma, which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice, heart and intuition.” Unlike Steve Jobs, I don’t know that my death is anywhere near imminent. I hope not; there are still a few things I want to do. But, I agree with him. I tell you this: you will never have more energy, more enthusiasm and more brain cells than you have now, I can also tell the male graduates in this hall that you will never have more hair than you have now. I know that from personal experience that is baldly evident. So, this is not a time for you to lament the period in which you live or to bemoan its circumstances. After all, your generation is the most educated, the best informed, the most tolerant of race and religion, the best prepared for competition in a globalized world. The Internet, the World-Wide Web, mobile phones, computers, Facebook and Twitter have opened up a world of instant knowledge and instant communication. Those things have freed your generation from offices and desks; it has even freed you from having to be within a country to work for its companies or to interface with the clients of such companies. Increasingly in the future, people will work for the world from anywhere in the world; and they can just as well work from home, as work in an office. Already within this University, lectures are being shared across campuses in three countries, and conferences are held through computer-based technology in which persons interface as if they are in the same room. I suspect that not all of you will remain in the disciplines in which you graduate today. In your lifetime, you will train in other fields and you will take advantage of new technologies that appear with astonishing regularity. You need not fear those developments, for if the history of our West Indian people has proved one thing it is that we have a genius for adaptation. As Carrie Gibson in her recent authoritative history of the Caribbean observed: “The West Indian character has everything to do with surviving the many brutalities, restrictions, and challenges served up by people from Europe and later the United States”. If we could – as we have - overcome the scale and consequences of those brutalities; if we could – as we have – fashion a West Indian identity and culture – from severed connections; if we could – as we have – make ourselves into middle income countries from the conditions of poverty in which colonialism left us, then the only thing between you and success is hard work. And, we should all recall that the only place where success comes before work is in the dictionary. I invite you all to go out and show that the world is your stage, and you are more than ready to play your part. Thank you very much.

|