The world is a very different place at 6,000 feet under the sea. Cold, lightless and with crushing pressure, one could easily assume that few creatures could survive at such a depth. But in certain places, not only can creatures survive the abyss; they have formed thriving undersea communities of exotic mussels, tube worms, prehistoric fish, crabs, shrimp and other species that are as unearthly as they are beautiful. These oases of life in the deep dark void are known as “cold seeps”, and thanks to an international team of explorers, including two Trinidadians and one faculty member from The UWI, one such seep has been discovered in the waters to the east of Trinidad and Tobago.

“It’s called a siphonophore,” Dr. Judith Gobin, Lecturer in Zoology at The UWI’s Department of Life Sciences in the Faculty of Science and Technology tells me. We are watching a short video clip of a sea creature that the crew of the Exploration Vessel E/V Nautilus captured on their expedition of the Southern Caribbean.

The creature is unreal, a column of seemingly both gas and solid with two long elegant feathers protruding from it. Up close the feathers aren’t feathers at all, more like structures made of transparent flower petals moving independently of each other. Strangest of all, the siphonophore is a “colony” animal, made up of many individual organisms living together as one slow drifting creature.

“It was an amazing experience,” Dr. Gobin says, perhaps seeing the wonder in my eyes.

For one week, Dr. Gobin and fellow Trinidadian, deep-sea biologist D. Diva Amon, joined the crew of the Nautilus. The Nautilus carries out research and exploration of the sea floor on expeditions all over the world, using advanced technology, 24-hour live streaming and inviting scientists, geologists and other researchers to partake in or even suggest missions. The ship is part of the Ocean Exploration Trust, which was founded in 2008 by Dr. Robert Ballard, who led the team that discovered the wreck of the Titanic in 1985. For one week, Dr. Gobin and fellow Trinidadian, deep-sea biologist D. Diva Amon, joined the crew of the Nautilus. The Nautilus carries out research and exploration of the sea floor on expeditions all over the world, using advanced technology, 24-hour live streaming and inviting scientists, geologists and other researchers to partake in or even suggest missions. The ship is part of the Ocean Exploration Trust, which was founded in 2008 by Dr. Robert Ballard, who led the team that discovered the wreck of the Titanic in 1985.

“It is an incredible operation and it is so well done, so precise,” Dr. Gobin says. From October 2, 2014, she served as a member of the Nautilus’s science team, working and forming friendships with crewmembers of various ages, races and genders from around the world.

“We all had to work two four-hour shifts up in the Van (the ships command centre where the video is viewed and decisions are made as to what images should be captured). Every shift there was eight or nine of us in the Van looking at six video screens. That number included two scientists, videographers and the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) pilots (the Nautilus team comprises 28 people while the ship’s crew is about 13-14),” she describes. “I was really impressed by the amount of women that were on the crew doing everything the men did. Some of the ROV operators were women.”

For Dr. Gobin, the ROVs, because of their sophisticated technology and the intricacy of their operations, were particularly fascinating.

“When you watch them pilot the ROV Hercules it is extraordinary. It has arms, it has cameras, it has thrusters that allow it to move in every direction. The arms can pick up samples and store them in containers. And this is a multi-million dollar piece of equipment, so the pilots cannot make mistakes with it,” she says.

Life in the deep

Dr. Gobin joined the team in Grenada, where they were continuing work they had begun last year exploring Kick’em Jenny, the Caribbean Sea’s most active deep-sea volcano. The UWI lecturer had been a member of that 2013 team as well, which she hoped would be able to explore Trinidad and Tobago’s undersea terrain at that time. However, circumstances prevented it from happening and were it not for the frantic efforts on Dr. Gobin’s part and support from several Government ministries it would not have happened this year either. The area, about 17 nautical miles east of Tobago, is oil and gas exploration territory, and is primarily the domain of the multinational energy companies. It took a major effort to get the necessary permissions for the expedition in the short timeframe.

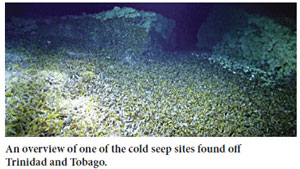

“We knew there were seeps but there isn’t much documentation,” Dr. Gobin explains. “We know the oil companies have some information on it as well but we do not have access to that. That’s why this was such a breakthrough, it was the first time we have underwater video being taken of a cold seep in our waters. It was exciting for me because it was all about Trinidad and Tobago. It was about exploration and understanding what we have.” “We knew there were seeps but there isn’t much documentation,” Dr. Gobin explains. “We know the oil companies have some information on it as well but we do not have access to that. That’s why this was such a breakthrough, it was the first time we have underwater video being taken of a cold seep in our waters. It was exciting for me because it was all about Trinidad and Tobago. It was about exploration and understanding what we have.”

And what did they find? In the words of Dr. Gobin, an amazing “array of life”.

Cold seeps are formed by seismic activity, the shifting of the earth’s plates on the sea floor. Through that activity, substances like methane and hydrogen sulfide seep through fissures into the water, creating “pools”. Bacteria metabolises these substances, in other words they use it as a source of fuel to survive. The term for this is “chemosynthesis” – obtaining energy from chemicals. This is different from “photosynthesis” obtaining energy from light, which is the basis of life as we know it, but which is impossible in the lightless environment of the deep sea.

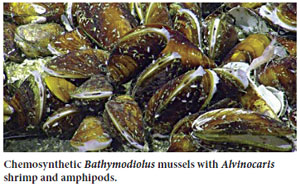

These bacteria form the base of the cold seep food chain, either as bacterial “mats” that other species can feed from directly, or through symbiotic relationships with species like mussels. At the Trinidad cold seep the Nautilus crew found a massive community of mussels and tubeworms.

“We found the largest mussels ever recorded last year at Kick'em Jenny (the species Bathymodiolus),” Dr. Gobin said. “This year the scientists were saying that here in Trinidad, it was the largest community of mussels that they had ever seen.”

The cold seep food chain can include snails, crabs, shrimp, certain species of deep-sea fish and octopus. This is all remarkable because these creatures are living in a lightless environment in temperatures as low as 4 degrees Celsius and 120 atmospheres of pressure (120 times the pressure we are accustomed to). The cold seep food chain can include snails, crabs, shrimp, certain species of deep-sea fish and octopus. This is all remarkable because these creatures are living in a lightless environment in temperatures as low as 4 degrees Celsius and 120 atmospheres of pressure (120 times the pressure we are accustomed to).

“These deep sea organisms have to be adapted to the pressure, the lack of oxygen, light and food. Many of these animals are blind,” Dr. Gobin said.

So what’s next for Dr. Gobin after this enormous find?

“For a coastal person (Dr. Gobin specialises in marine biology) this experience made me very interested in the deep sea. I will definitely do more deep-sea work. My trip last year (to Kick’em Jenny) was the highlight of my career and this year was outstanding because it was in Trinidad and Tobago.”

Looking at the siphonophore, gliding along in that hidden world so far beneath the waves, who wouldn’t want to know more? |